Kenton Clymer - A Delicate Relationship: The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945

Here you can read online Kenton Clymer - A Delicate Relationship: The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Cornell University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Delicate Relationship: The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945

- Author:

- Publisher:Cornell University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

A Delicate Relationship: The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Delicate Relationship: The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

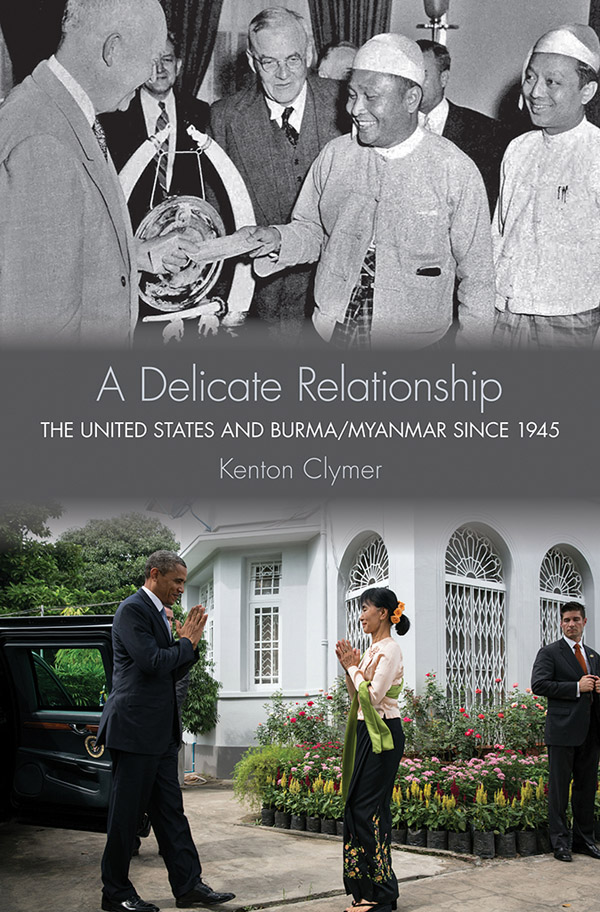

In 2012, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president ever to visit Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. This official state visit marked a new period in the long and sinuous diplomatic relationship between the United States and Burma/Myanmar, which Kenton Clymer examines in A Delicate Relationship. From the challenges of decolonization and heightened nationalist activities that emerged in the wake of World War II to the Cold War concern with domino states to the rise of human rights policy in the 1980s and beyond, Clymer demonstrates how Burma/Myanmar has fit into the broad patterns of U.S. foreign policy and yet has never been fully integrated into diplomatic efforts in the region of Southeast Asia.

When Burma, a British colony since the nineteenth century, achieved independence in 1948, the United States feared that the country might be the first Southeast Asian nation to fall to the communists, and it embarked on a series of efforts to prevent this. In 1962, General Ne Win, who toppled the government in a coup dtat, established an authoritarian socialist military junta that severely limited diplomatic contact and led to a period in which the primary American diplomatic concern became Burmas increasing opium production. Ne Wins rule ended (at least officially) in 1988, when the Burmese people revolted against the oppressive military government. Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as the charismatic leader of the opposition and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. Amid these great changes in policy and outlook, Burma/Myanmar remained fiercely nonaligned and, under Ne Win, isolationist. The limited diplomatic exchange that resulted meant that the state was often a frustrating puzzle to U.S. officials.

Clymer explores attitudes toward Burma (later Myanmar), from anxious anticommunism during the Cold War to interventions to stop drug trafficking to debates in Congress, the White House, and the Department of State over how to respond to the emergence of the opposition movement in the late 1980s. The juntas brutality, its refusal to relinquish power, and its imprisonment of opposition leaders resulted in public and Congressional pressure to try to change the regime. Indeed, Aung San Suu Kyis rise to prominence fueled the new foreign policy debate that was focused on human rights, and in that climate Burma/Myanmar held particularly large symbolic importance for U.S. policy makers. Congressional and public opinion favored sanctions, while U.S. presidents and their administrations were more cautious. Clymers account concludes with President Obamas visits in 2012 and 2014, and visits to the United States by Aung San Suu Kyi and President Thein Sein, which marked the establishment of a new, warmer relationship with a relatively open Myanmar.

Kenton Clymer: author's other books

Who wrote A Delicate Relationship: The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.