Preface

The term Myanmar needs some clarification. First, spelled Mranma and Myanma in Old and Modern Burmese script respectively, it is not a noun but an adjective that modifies the noun that follows it, so that Myanma Pyay (or Pyi) is a reference to the country, Myanma Lu Myo to the people and Myanma Saga to the language. To use the term Myanmar as a noun is, in Burmese, tantamount to using the word American for America, so that one would be saying I am going back to American rather than I am going back to America. Nevertheless, Myanmar, used as a noun, is now the legal English term for the country recognized by the United Nations.

Second, Myanmar is not a new word coined only in 1989 by the military Government to replace the term Burma as often contended by the international media (and even some scholarly works). On the contrary, its Old Burmese equivalent (Mranma) has been used for the state and country in much the same way since at least the early twelfth century if not earlier. Similarly, the countrys place-names; Yangon was only much later anglicized as Rangoon by the British, Pyi as Prome and Muttama as Martaban. To Burmese speakers, who currently represent well over 87 per cent of the population, the Burmese versions have always been known and used as such.

Indeed, it is Burma that is actually the new (and foreign) term, likely created only in the nineteenth century and the British period. It is certainly not an indigenous word and cannot be found as such in either the national language or any minority languages of the country prior to that era. Although the word Burma may have been phonetically derived from the Burmese word Bama (the colloquial equivalent of Myanma), Burma per se is still English, and still a colonial term imposed on the countrys people without their knowledge and/or consent.

Even during the height of the colonial period when English was the official language of state, if one were to ask ordinary Burmese speakers who did not speak English (which constituted the vast majority of thepopulation) what the name of the country was, they surely would have replied Myanma Pyi, not Burma, and if asked the name of the capital at the time, would have said Yangon, not Rangoon. It was only amongst the very small English-language-speaking elite circles that their anglicized equivalents were used.

Third, many ex-colonies since independence have returned to using indigenous place-names, understandably after humiliating colonial experiences. Sri Lanka and Myanmar are just two examples while in India Bombay is once again Mumbai, Calcutta is Kolkata and Madras, Chennai. Yet whereas Sri Lanka and India are not ostracized for doing this, Myanmar is, indicating that the reason a few rogue nations continue to insist on using the term Burma rather than Myanmar is obviously political. The word Burma has no legal standing internationally, is clearly exogenous, and only perpetuates rather than resolves current tensions.

To clarify further, in American academic usage, the word Burman refers to the ethno-linguistic group and Burmese to citizens of the nation. In British academia, however, the two are reversed. Yet neither is correct, for there is no such distinction made in Burmese itself between the ethno-linguistic and the national group; both are Myanma (or Bama). That distinction between Burman and Burmese (like the word Burma) is also a colonial creation that appears to have followed the differences perceived between British and English so important to the British colonial power. And, of course, there is no such thing as Myanmarese.

For the sake of convenience this book uses the current internationally recognized legal term Myanmar for the country, Burmese for the national group and language, and Burma when the context dictates; that is, usually for references made during the colonial period when official statements or records are cited or proper names in English that use the term Burma. We also retain the former English spellings of well-known words such as Upper and Lower Burma, Irrawaddy, Salween, Ava, Pagan, Moulmein, Martaban, Pegu, Mandalay and Arakan to minimize confusion.

Prologue:

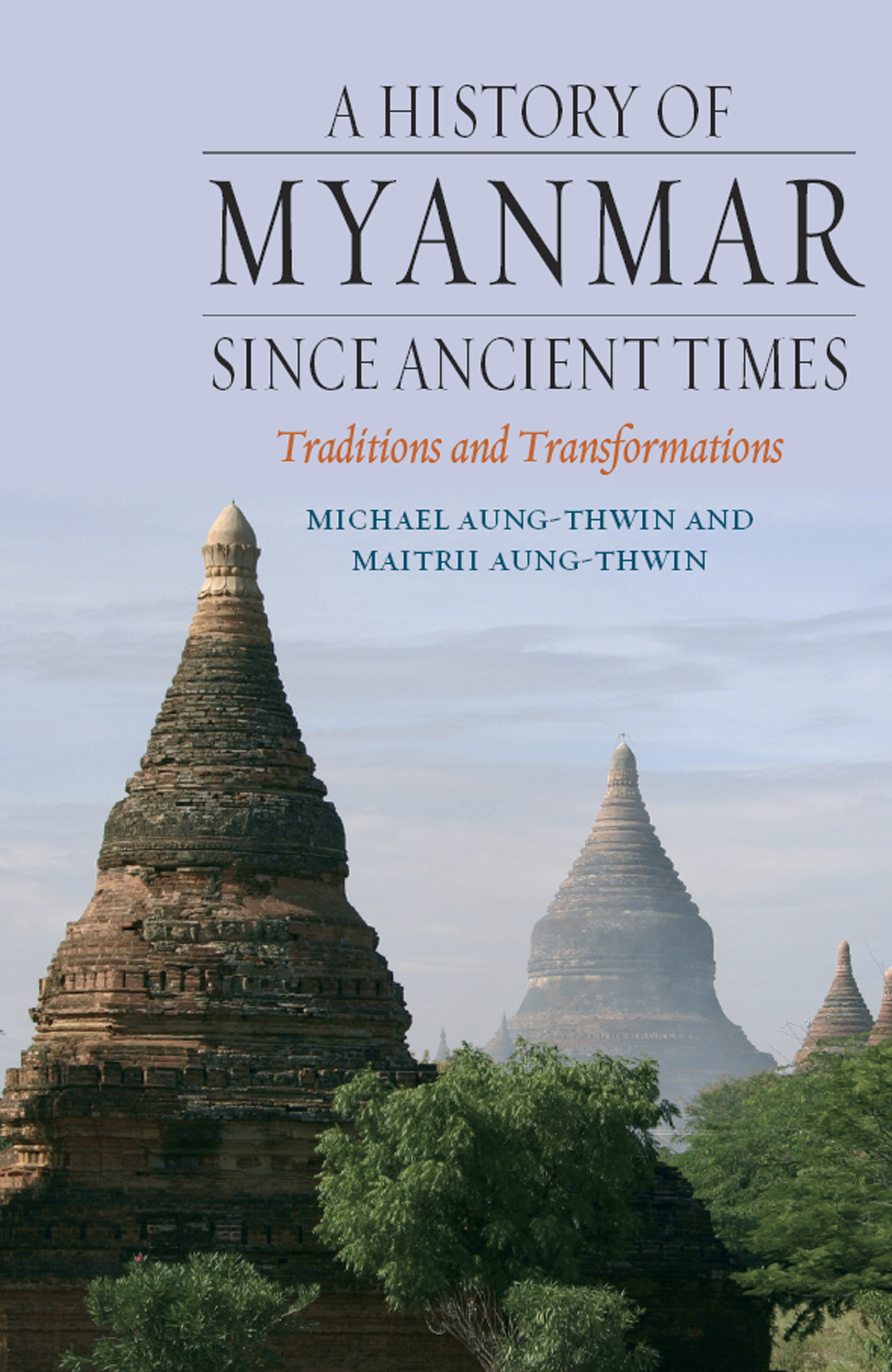

A Synthesis of Old and New

As the Silk Air jet from Singapore lands at the small new modern Yangon International Airport where tall grass rather than concrete and urban sprawl meets the runway one is a bit puzzled. Has time stood still or moved forward in Myanmar? The ambiguity is warranted, for both observations are accurate. The country today is struggling to accommodate its past with its present, attempting to integrate long-standing cultural traditions and historical trends with more immediate, short-term, mainly externally generated economic and geo-political realities, resulting in both a fusion and a tension between old and new. Thus, while this Prologue introduces the reader to present day Myanmar, the following chapters in flashback fashion explain how it got there.

Once inside the clean, air-conditioned and orderly terminal, legal entry to the country is quick and easy. Immigration is staffed mainly by women wearing Western-style uniforms but with traditional thanakha paste on their faces, and what was once a manual affair with long lines, many sheets of paper being stamped, scrutinized and approved by many different people is now done with a few clicks of the keyboard on computers (even visa-on-arrival is now available.)