Contents

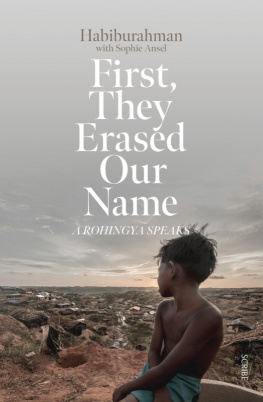

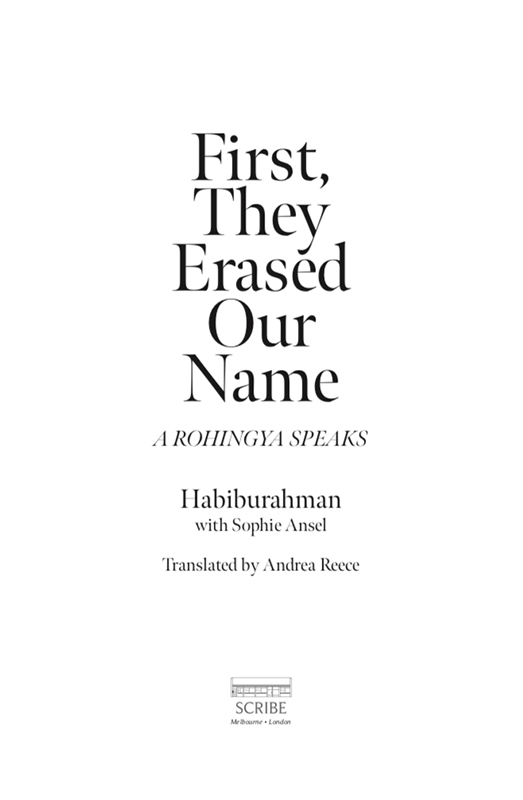

First, They Erased Our Name

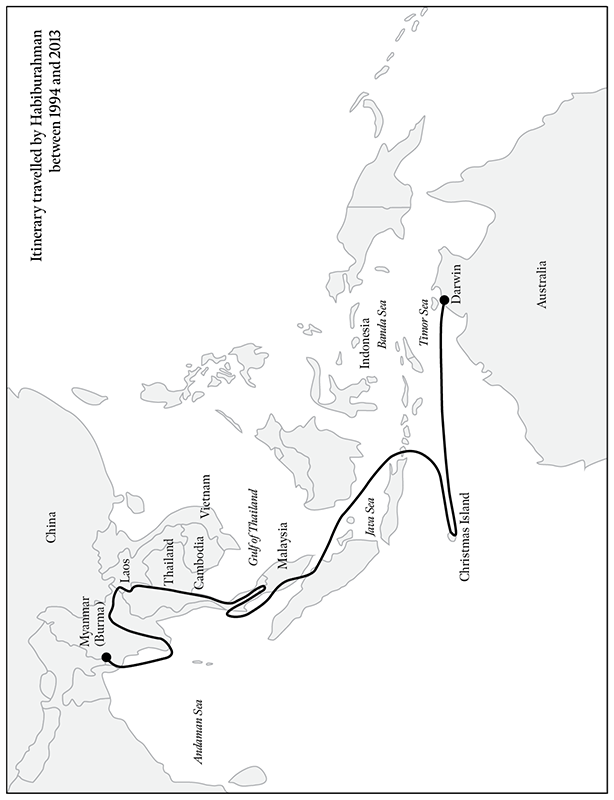

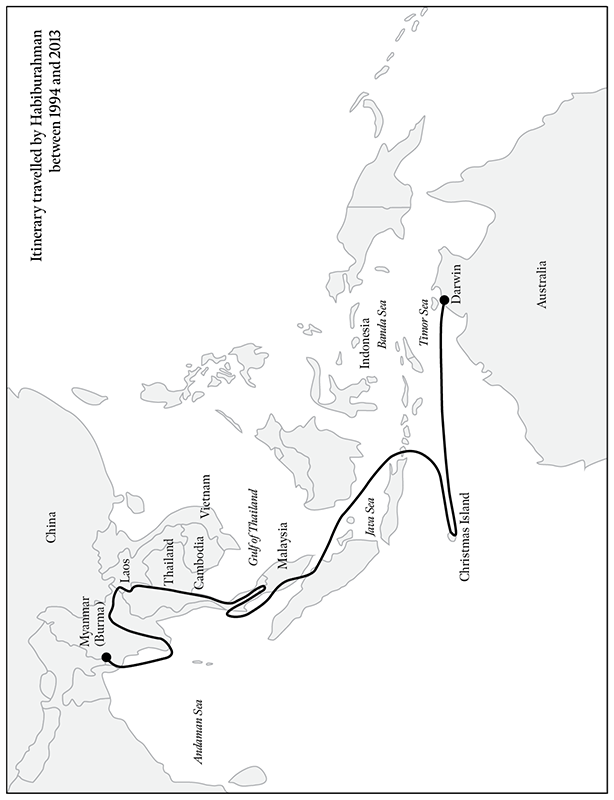

Habiburahman , known as Habib, is a Rohingya. Born in 1979 in Burma (now Myanmar), he escaped torture, persecution, and detention in his country, fleeing first to neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia, where he faced further discrimination and violence, and then, in December 2009, to Australia, by boat. Habib spent 32 months in detention centres before being released. He now lives in Melbourne. Today, he remains stateless, unable to benefit from his full human rights. Habib founded the Australian Burmese Rohingya Organization (ABRO) to advocate for his people back in Myanmar and for his community. He is also a translator and social worker, the casual support service co-ordinator at Refugees, Survivors and Ex-Detainees (RISE), and the secretary of the international Rohingya organisation Arakan Rohingya National Organisation (ARNO), based in the UK. In 2019, he was made a Refugee Ambassador in Australia. The hardship and the human rights violation Habib has faced have made him both a spokesperson for his people and a target for detractors of the Rohingya cause.

Sophie Ansel is a French journalist, author, and director, who lived in South Asia for several years. It was during a five-month stay in Myanmar that she first encountered the Rohingya people and heard of their plight. She returned to the country several times, and also visited the refugee communities in neighbouring countries like Thailand and Malaysia, where she met Habib in 2006. Habib helped Sophie to better understand the persecution faced by the Rohingya, and she has been advocating for their cause since 2011. When the Myanmar government accelerated the genocide of the Rohingya in June 2012, while Habib was detained in Australia, she helped him to write his story, and the story of his people.

Andrea Reece is a translator of novels, short stories, and works of non-fiction from French and Spanish.

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

3754 Pleasant Ave, Suite 100, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 USA

First published in English by Scribe in 2019

Originally published in French as Dabord, ils ont effac notre nom Editions de la Martinire, une marque de la socit EDLM, Paris, 2018

This edition published by special arrangement with EDLM in conjunction with their duly appointed agent 2 Seas Literary Agency

Text copyright Habiburahman and Sophie Ansel 2018

Translation copyright Andrea Reece 2019

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

This book is a true story based on the authors best recollections. Some names and places have been changed for reasons of security and privacy.

The moral rights of the authors and translator have been asserted.

9781925849110 (Australian edition)

9781912854035 (UK edition)

9781947534858 (US edition)

9781925693720 (e-book)

Catalogue records for this book are available from the National Library of Australia and the British Library.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

scribepublications.com

To the Rohingya,

To the memory of those whose blood continues to flow

into the soil of Arakan.

To all the weary stateless people who have fled and still roam

the oceans, jungles, and highways of the world,

hoping to survive.

To you, the reader, may you tell our story,

which has been stifled by propaganda, racism, fascism,

and deadly hatred.

May the truth one day be known and a light shone

on our tragedy, the hidden history of Burma.

To my family, to my father and my mother,

To tolerance and peace,

To life and love.

This book is not only my story.

It is the chronicle of a genocide.

The ogre of Burma is born

The dictator U Ne Win has presided over a reign of terror in Burma for decades. In 1982, he has a new project. He is planning to redefine national identity and fabricate an enemy to fuel fear. A new law comes into force. Henceforth, to retain Burmese citizenship, you must belong to one of the 135 recognised ethnic groups, which form part of eight national races. The Rohingya are not among them. With a stroke of the pen, our ethnic group officially disappears. The announcement falls like a thunderbolt on more than a million Rohingya who live in Arakan State, our ancestral land in western Burma. The brainwashing starts. Rumours and alarm spread insidiously from village to village. From now on, the word Rohingya is prohibited. It no longer exists. We no longer exist.

I am three years old and am effectively erased from existence. I become a foreigner to my neighbours: they believe that we are Bengali invaders who have entered their country illegally and now threaten to overrun it. They call us kalars , a pejorative term expressing scorn and disgust for dark-skinned ethnic groups. In a different time and place, under different circumstances, kalar would have meant wog or nigger. The word is like a slap in the face; it undermines us more with each passing day. An outlandish tale takes root by firesides in thatched huts across Burma. They say that because of our physical appearance we are evil ogres from a faraway land, more animal than human. This image persists, haunting the thoughts of adults and the nightmares of children.

I am three years old and will have to grow up with the hostility of others. I am already an outlaw in my own country, an outlaw in the world. I am three years old, and dont yet know that I am stateless. A tyrant leant over my cradle and traced a destiny for me that will be hard to avoid: I will either be a fugitive or I wont exist at all.

Grandmas stories

1984

In the candlelit glow of the hut, I half open my eyes through heavy eyelids and see Grandmas wrinkled and kindly face. Her features are blurred by the steam from the pot that she is stirring. The smell of rice and the crackling fire rouse me from my torpor. Grandma comes over and sits down cross-legged on the large grass mat that covers the mud floor. She wraps her arms around me and mops my burning forehead with a wet cloth scented with herbs that Dad has gathered in the forest. Next to her, Mum hums a barely audible tune as she rocks my little sister Nojum who is latched firmly on to her breast. Grandma lifts a spoonful of broth to my mouth. I close my eyes again, exhausted by illness. Her voice resonates like a distant echo: Keep going, little Habib. Drink this down and itll make you strong again. A slight fever like this isnt going to finish you off. Be brave, my little one.

Her words continue uninterrupted, barely distinguishable from the ambient noise. I dont know whether she is talking to me, Mum or Dad, or to the tormented figures from another time and place who live on in the depths of her memory. Fleeing, endlessly roaming, shrieking and screaming for help. The ghosts of our family and of our people who perished, decapitated by swords or burnt to death. This is where my fear of fire started: back then, the flames were always populated by Grandmas wailing ghosts.

She nuzzles into the hollow of my neck a sign of infinite affection and her voice pulls me back from sleep, into the story of our cursed people.

Next page