The World as Idea

In The World as Idea, Charles P. Webel presents an intellectual history of one of the most influential concepts known to humanitythat of the world.

Webel traces the development of the world through the past, depicting the history of the world as an intellectual construct from its roots in ancient creation myths of the cosmos, to contemporary speculations about multiverses. He simultaneously offers probing analyses and critiques of the world as idea from thinkers ranging from Plato, Aristotle, and St. Augustine in the Greco-Roman period to Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Merleau-Ponty, and Derrida in modern times. While Webel mainly focuses on Occidental philosophical, theological, and cosmological notions of worldhood and worldliness, he also highlights important non-Western equivalents prominent in Islamic and Asian spiritual traditions. This ensures the book is a unique overview of what we all take for granted in our daily existence, but seldom if ever contemplatethe world as the uniquely meaningful environment for our lives in particular and for life on Earth in general.

The World as Idea will be of great interest to those interested in the concept of world as idea, scholars in fields ranging from philosophy and history to political and social theory, and students studying philosophy, the history of ideas, and humanities courses, both general and specialized.

Charles P. Webel, Ph.D., is currently a Professor and Guarantor of the School of International Relations at the University of New York in Prague. A five-time Fulbright Scholar and a research graduate of the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California, he has studied and taught at Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley, where he received his Ph.D. He is the author or editor of many books, including Peace and Conflict Studies (with David Barash), the standard text in the field, as well as Terror, Terrorism, and the Human Condition, and The Politics of Rationality.

DOI: 10.4324/9781315795171-1

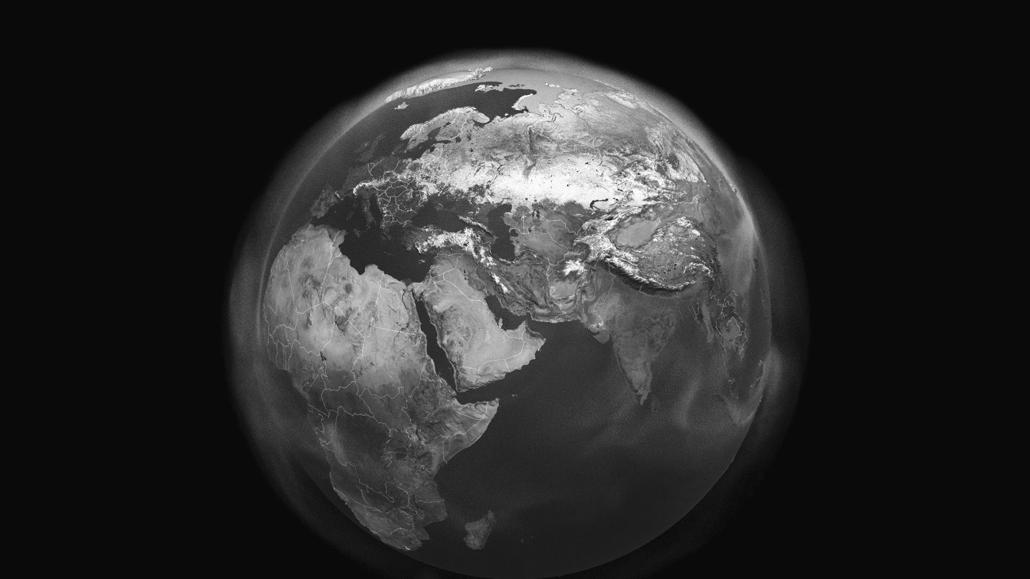

NASA photo of the Eastern Hemisphere, partially covered with methane gas.

Source: NASA.

The world does and does not exist. Behind this paradoxical assertion lie the facts that the world is a linguistic and historical construction, not an ontological given, and therefore exists only insofar as meaning-creating organisms frame the boundaries of their being-in-this-world.

The world is thus an abstraction, a concept, or idea, but a vital one. Our fate literally depends on it.

We use the term the world to provide a limit to our possible experiences and perceptions while living on Earth, and also to distinguish human civilization as a whole from the rest of life, both terrestrial and extra-terrestrial. In this book, I am using the phrase the world to refer to the totality of human artifacts imposed on this planetary orb on which our species has existed.

The world is normally taken-for-granted. It is assumed simply to be there, undeserving of definition, so self-evident that one doesnt need explain it.

Nonetheless, it is useful to distinguish the world from this world. The former designates a general context for the possible experiences of sentient creatures as a whole; the latter denotes the specific limits within which your and my lives can be lived and interpreted.

The world is an impersonal factual framework for description and analysis: it is everything that is the case, as the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein described it in the beginning of his book the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The world is the scaffolding, the skeletal structure, upon which the flesh, bones, and brains that constitute this world of possible experience has been erected.

This world, in contrast, is a subjective and intersubjective boundary for our lived experience. Those two words, this world, denote the personalized horizon that renders the world potentially meaningful and value-laden. It is how I see the world, what it means to me and others, what its like to be-in-the-world, and how the feelings, desires, and perspectives we have about the world are socialized, historicized, politicalized, and individualized. How the words this world are used thus depend on their users.