THE

AWAKENING

Christ Treading the Beasts , mosaic in the Archbishops Chapel, Ravenna Jos Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 4.0

THE

AWAKENING

A History of the Western Mind

AD 500 - 1700

CHARLES FREEMAN

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

For my daughter Cordelia

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2020 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright Charles Freeman, 2020

The moral right of Charles Freeman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN [ HB ]: 9781789545623

ISBN [ E ]: 9781789545647

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

www.headofzeus.com

Contents

The Saving of the Texts, 500750

Charlemagne Restores the Discipline of Learning

Conformity and Diversity in the Christian Communities of the Late First Millennium

Authority and Dissent in the Medieval Church, 10001250

Abelard and the Battle for Reason

The Cry of Libertas : The Rebirth of the City-State

Success and Failure within the Medieval University

Medieval Philosophy: A Reawakening or a Dead End?

Dante, Marsilius and Boccaccio and their Worlds

The Printing Press: What Was Published and Why?

The Loss of Papal Authority and the Rise of the Laity, 13001550

Defining Global Space: The Mapping of the New World

How Europe Learned to See Again: Leonardo and Vesalius

Exploring the Natural World in the Sixteenth Century

Imagining Princely Politics, from Utopia to the Machiavellian Ruler

Broadening Horizons: From the Laocon to the Academies

Encountering the Peoples of the Newe Founde Worldes, 14921610

The Reformation and the Reassertion of Christian Authority?

The epithets barbarous and civilized occur so frequently in conversation and in books, that whoever employs his thoughts in contemplation of the manners and history of mankind will have occasion to consider, with some attention, both what ideas these words are commonly meant to convey, and in what sense they ought to be employed by the historian and moral philosopher.

James Dunbar, Essay on the History of Mankind in Rude and Cultivated Ages (1780)

T he monastic foundation of the Chora in Istanbul, formerly the great Christian city of Constantinople, is a rare survival of a church with its original medieval decorations in what has been an Islamic city since 1453. Founded in the fourth century as a monastery of the Holy Saviour in the Fields, outside the walls built by Emperor Constantine ( chora designates the open space around a city), it then became enclosed within the later, fifth-century, set of walls but never lost its name. It is famous today for its wonderful fourteenth-century mosaics and, in a fresco in a side chapel, a stunning portrayal of the resurrected Christ entering Limbo to release the souls there.

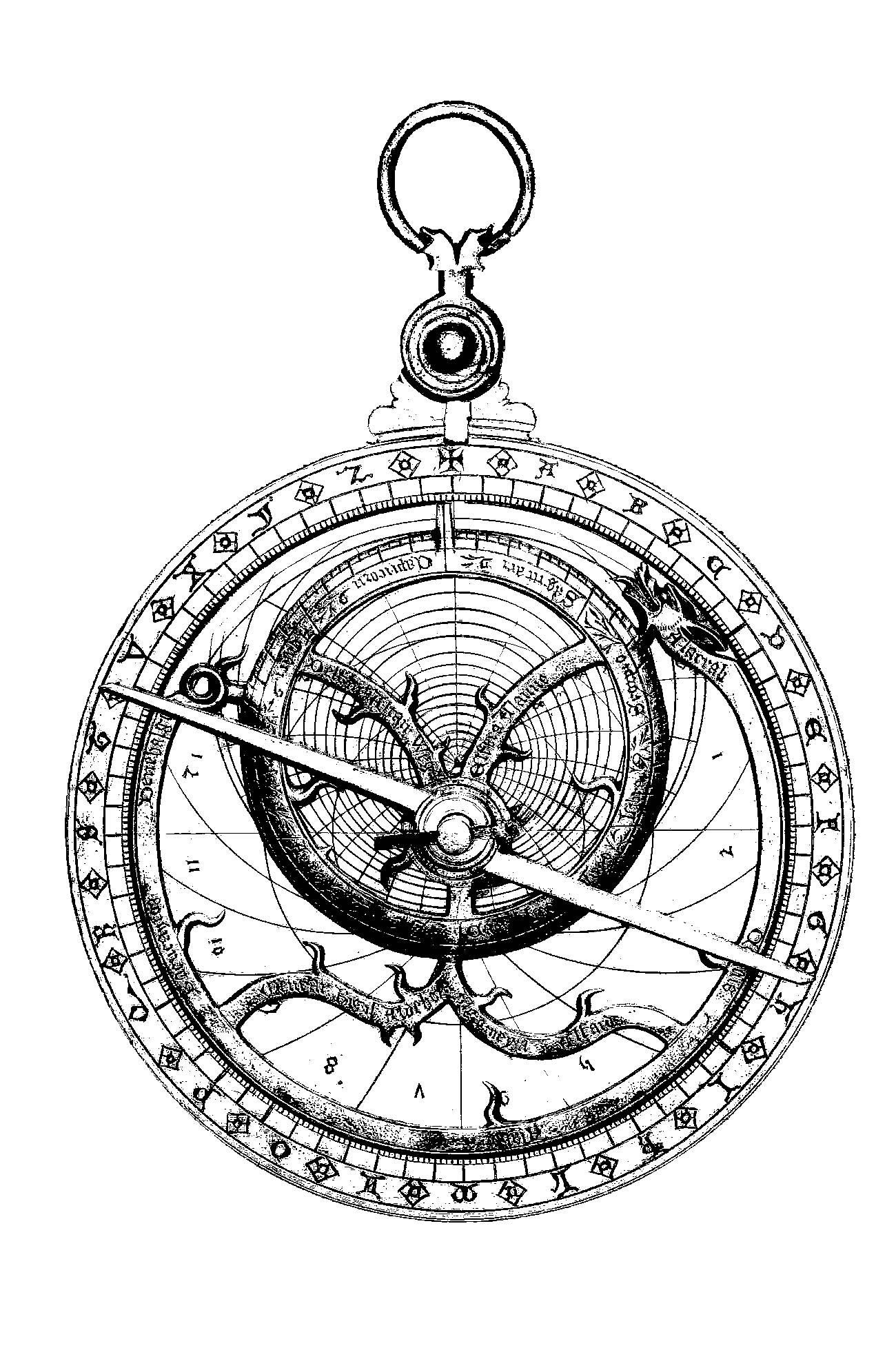

It was in 1295, just before the mosaics were created, that one Maximus Planudes, an erudite Byzantine Greek monk who was fascinated by the ancient world, tracked down in the library the one manuscript he was looking for, a copy of Claudius Ptolemys Geographike Hyphegesis ( Guide to Drawing the Earth ). The rediscovery of the Geographike in the late thirteenth century, 1,000 years after it had been written down and presumed lost, was a seminal moment in the awakening of the western mind.

Planudes was not the only copy of the Geographike to survive; another was known to the Arabs and had been translated into Arabic in the ninth century. It was used by the nobly born cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who had been invited to join the cultured court of the Norman king of Sicily, Roger II, in about the year 1138. Al-Idrisi adopted Ptolemys concepts of longitude and latitude to create seventy regional maps in which all the sections were drawn to the same scale, the first time this had been done. The maps were recognizably accurate in delineating the known world of Ptolemy even though, according to Arabic convention, north and south were reversed. (Most illustrations of al-Idrisis maps follow the western convention of the north at the top.) They reflected the faith of its maker, so they showed the Arabian peninsula and Mecca at the centre and the text was in Arabic, but al-Idrisi used Greek, Latin and Arabic sources without discrimination. The open-minded Roger II took such an interest in the project that the volume containing the maps and accompanying text became known as the Tabula Rogeriana ( The Book of Roger ). Following the death of Roger who had proved such an enthusiastic patron to al-Idrisi in 1154, the climate of the times was hardly conducive to the dissemination of the work of the Tabula s creator. With the crusades dominating the Christian imagination, an Islamic map of this date, even one produced at a European court, was hardly likely to be welcomed. Al-Idrisis pioneering work therefore remained little known in Europe. Yet it serves to highlight one of the major themes of this book: the Arabs were well ahead of the Europeans in intellectual life at least until the thirteenth century and they were to make a formidable contribution to the revival of western learning.

Al-Idrisis 1154 map of the world as tabulated by Ptolemy is shown with the Arabic world at the top and Europe at the bottom.

A modern copy of the Tabula Rogeriana , made by Konrad Miller; Wikimedia Commons

The copy of Ptolemy found by Planudes proved more influential in Europe. The monk took his find to the Byzantine emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos, who was equally excited by the discovery. He soon had his finest copyists working on the manuscript and his best mathematicians plotting out the maps. Planudes added his own explanatory texts, translating the Greek numerals into the Arabic ones that we use today. Three copies of their atlases survive, in large folios with all the twenty-six maps Ptolemy had given co-ordinates for. Manuel Chrysoloras, a scholar from Constantinople, brought one copy to Florence when he initiated the teaching of Greek there in 1396. By 1410 the first Latin translation of the original Greek text had been made by one of Chrysolorass students, the Tuscan Jacobus Angelus, who dedicated it to Pope Alexander V. For the humanists the Geographike became honoured as another window into the minds of the ancients and as a text that was clearly superior to its competitors. It gradually supplanted medieval conceptions of the geography of Europe, the Christian mappae mundi and the portolan charts that used compass bearings to plot the ports of the Mediterranean. By the end of the fifteenth century, the Geographike was still dominating the world of the cartographers. As knowledge of the Earths land masses expanded, Ptolemys findings could be adapted to fit these new discoveries. So while Ptolemy knew nothing of Scandinavia the northernmost point in the Geographike was the semi-mythical island of Thule at 63 degrees his system could be used to incorporate the region in newly drawn maps.