I have to thank my agent Bill Hamilton for encouraging me to concentrate on the story of the horses rather than on the more general theme of Venice, which I had at first proposed. His faith that they would have a remarkable history was well placed. At Time Warner, my editor Richard Beswick was instrumental in advising on the shape of the book as it matured. Once the book was written, Gillian Somerscales corrected my clumsier sentences and spelling discrepancies with care and tact, while Linda Silverman tracked down not only those pictures I had requested but many more of interest that we were able to use. Viv Redman oversaw the production process with gentle yet firm efficiency and I am grateful to Sue Phillpott for proofreading and Dave Atkinson for compiling the index.

A. D. 381

THE CLOSING OF THE WESTERN MIND

EGYPT, GREECE AND ROME

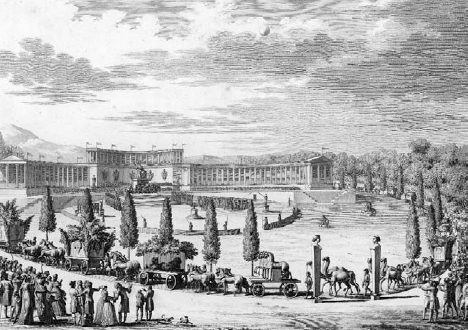

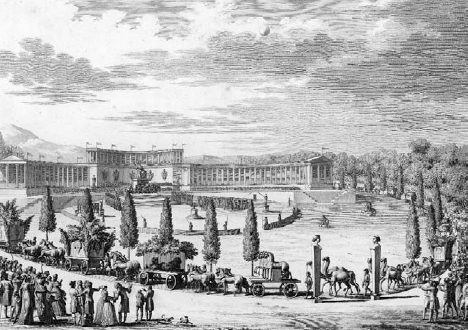

TOWARDS THE END OF JULY 1798 AN EXTRAORDINARY procession wound its way through the streets of Paris towards the Champ de Mars, the military parade ground which had been adopted by the Parisians of revolutionary France as the site of major festivals. Much of it consisted of large packing cases whose contents could only be guessed at from slogans on the side which proclaimed them to be art treasures. On open display there were animals among them caged lions, a bear and even a pair of dromedaries paraded alongside tropical plants, including palm, banana and coconut trees; but the only art works actually visible to the curious onlookers were four horses of gilded metal, larger than life-size, arrayed on a wagon which was itself drawn by six horses. They were known to have come from Venice, where they had been seized by Napoleon when the city had surrendered to him.

Those familiar with ancient history might have guessed that this was an attempted re-enactment of a Roman triumphal procession, and they would have been right. What they saw arriving in Paris were the victory spoils of one of Frances most successful military commanders: Napoleon Bonaparte, who still only twenty-eight had recently conquered much of Italy. Napoleon had followed the great Roman conquerors of the past in stripping his enemies of many of their finest works of art and taking them back to his own capital. The city which had suffered most from his looting was, ironically, Rome itself, where the pope, Pius VI, had given up some of the most prestigious of his possessions: world-renowned classical statues, among them the Capitoline Venus, the Laocon, and the Belvedere Apollo. With this in mind, the assembled Parisian crowds had been given a song to sing:

The horses make their triumphal entry into Paris in July 1798. The columned building at the far end of the Champ de Mars is the Temple of the Fatherland where the horses and other trophies were received by the academicians. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Rome nest plus dans Rome

Elle est tout Paris

Rome is no longer in Rome, it is all in Paris. And indeed, as well as the statues, which themselves made Paris the most richly endowed city in original classical art in Europe, the conqueror had brought home a comparable haul of Renaissance treasures. Among the trophies crammed into those packing cases was a startling number of sixteenth-century paintings by masters such as Raphael, Correggio, Titian and Tintoretto.

When news of Napoleons plunder had first reached Paris, many had wondered whether the French government, the Directory bourgeois and unimaginative when compared with the fervour of the earlier revolutionary regimes would accept the treasures into this new Rome with a celebration worthy of the occasion. No one had seemed prepared to put up the money to mount a proper display, and the commissioners who had selected the works in Italy began to worry. Will we let the precious booty from Rome arrive in Paris like charcoal barges and will we have it disembarked on the Quai du Louvre like crates of soap? said one. Then a government official had the inspired idea of asking Napoleon himself to finance the transport and display of the hoard. Napoleon had been assiduous in proclaiming the extent of his gains in letters to the Directory, and it was clear that he saw them as valuable propaganda for himself as much as works of art won for the nation. He would not be able to lead the celebrations himself he was about to embark on his expedition to Egypt but a triumphal procession modelled on those of republican Rome could be staged in his absence. So, once the ministry of foreign affairs had announced Napoleons agreement to the proposal, a formal approach was made by the minister of the interior to the Directory on behalf of the commissioners and, it was claimed, poets, philosophers, and public officials, that all those who feel the need of restoring public spirit and to increase national pride by having the spoils of conquered peoples pass before the eyes of our people, all join in requesting that the day that these fruits of our victories enter into Paris be celebrated by a festival.

The date of the festival, however, was continually postponed as the logistics of transporting so many heavy crates were sorted out. The horses and other treasures had come by sea from Venice, while those from Rome had been loaded on to ships at Leghorn(Livorno); all were disembarked at Marseilles, from where they came by barge up the French canal network. Their reception in Paris was eventually fixed for 27 and 28 July, when it would coincide with the fourth anniversary of the overthrow of an earlier casualty of the revolution, the tyrant Maximilien Robespierre.

That the revolutionary leaders should look to classical Rome for inspiration was understandable. Many of them had received a traditional classical education, and even before 1789 republican Rome Rome in the period from the overthrow of the king Tarquinius Superbus in 509 BC to the assumption of power by Augustus, Romes first emperor, in 27 BC had been upheld as a model of civic virtue in which citizens dedicated their energies to their country in both peace and war. The procession of 1798 was modelled on one held in Rome in 167 BC by the conqueror of Macedonia, Aemilius Paulus. His exploits and the victory procession itself had been described in the Lives of Plutarch, a Greek philosopher and biographer of the first and second centuries AD who was widely read in the eighteenth century. According to Plutarch, the triumph had lasted over three days, the first of which had been taken up with a parade of 250 wagons full of works of art. The second day had been devoted to the piles of armour stripped from the enemy, the third to gold plate and coins and to the display of Perseus, the defeated Macedonian leader, and his family. In the Paris triumph there were again three sections, but this time the divisions reflected not the generic types of booty but the preoccupation of Enlightenment thinkers with the classification of knowledge: Napoleons prizes were categorized as natural history, books and manuscripts and fine arts. Each section was provided with an escort of foot troops and cavalry, and a military band to lead the exhibits. The natural history section included the banana, palm and coconut trees, which came from Trinidad; the lions and dromedaries, from Africa; and the bear, which had had a less exotic home a zoo in Bern. An early draft of the plans required that the antiquities be dedicated at the Altar of the Fatherland on the Champ de Mars, in the same way that Roman victors such as Aemilius had offered theirs to the Temple of Jupiter, the Father of the Gods, on the Capitoline Hill in Rome. In the event the suggestion was replaced by a more sober one in which political leaders and members of the august Acadmie Franaise, the arbiter of French language and culture, would welcome the antiquities on behalf of the French government and its learned institutions. Only one of the objects the most sacred of all, a bust of Junius Brutus, the Brutus who had assassinated the dictator Julius Caesar, from the Capitoline Museum in Rome was to be placed on a pedestal in front of the altar, where it would evoke Frances own overthrow of monarchy. The rest were destined for display in the city or in the new museum planned in the former royal palace of the Louvre.

![Bosworth - Italian Venice: a history[Electronic book]](/uploads/posts/book/194557/thumbs/bosworth-italian-venice-a-history-electronic.jpg)