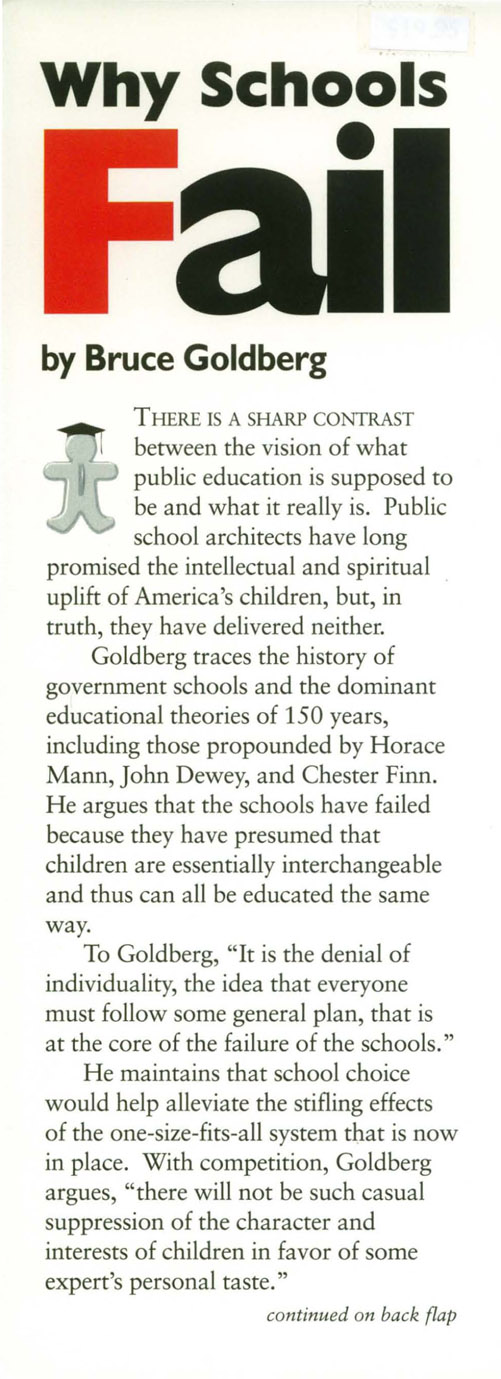

Why Schools

Fail

Why Schools

Fail

BRUCE GOLDBERG

Washington, D.C.

Copyright 1996 by the Cato Institute.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goldberg, Bruce, 1937-

Why schools fail / Bruce Goldberg. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 1-882577-39-6. ISBN 1-882577-40-X (pbk.)

EducationAims and ObjectivesUnited States. 2. EducationUnited StatesPhilosophy. 3. Education changeUnited States. I. Title

LA212.G64 1996

Cover Design by Mark Fondersmith.

Printed in the United States of America.

C ATO I NSTITUTE

1000 Massachusetts Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

To the memory of my mother

Gloria Goldberg

Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty

Introduction

In 1959 James B. Conant, former president of Harvard, writing about the American school system, said, "It works, most of us like it, and it appears to be as permanent a feature of our society as most of our political institutions." Given the widespread support for public schooling, there are probably not many people who would quarrel with the observation that the institution is permanent. Today, however, many people might hold that Conant somewhat overstated the case for his first two claims. For if there are those who do like the public school system, there are also many who do not. Dissatisfaction with schooling is widespread at all levels. Among high school students the dropout rate is 25 percent. A third of all new teachers leave the teaching profession after two years. Every day more than a million children are required to take psychoactive drugs so that their behavior in school will be "manageable."

Facts like those have led some observers to conclude that if the system can be said to be working, it is doing so very poorly. Within 10 years of Conant's optimistic study of high schools, there were calls for a complete restructuring, or even abandonment, of formal education, and the bestseller list featured such titles as Crisis in the Classroom, The Underachieving School, and Deschooling Society. The central question raised by those and other works was, Why is the system not working in anything like the way intended?

What seems undeniable is that there is a substantial contrast between the vision of what public education is supposed to be and the reality of schooling itself. Educators have tended to portray schooling in glowing terms. Horace Mann, the "father" of the public school system in America, claimed that the process of schooling would "build up the nature of the child into a capacity for the intellectual comprehension of the universe and a spiritual similitude to its Author."

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the schools have fallen somewhat short of achieving that vision. As marty observers have seen them, they are not the benevolent, beneficial places Mann envisioned. Schools are often, in effect if not in intent, rather dreadful places in which to spend time. Charles Silberman, then an editor of Fortune magazine, wrote in Crisis in the Classroom,

It is not possible to spend any prolonged period visiting public school classrooms without being appalled by the mutilation visible everywheremutilation of spontaneity, of joy in learning, of pleasure in creating, of sense of self. The public schools ... are the kind of institution one cannot really dislike until one gets to know them well. Because adults take the schools so much for granted, they fail to appreciate what grim, joyless places most American schools are, how oppressive and petty are the rules by which they are governed, how intellectually and esthetically barren the atmosphere.

When critics characterize the failure of schooling in terms of the mutilation of the child's sense of self or the suppression of the child's individuality, as opposed to declining Scholastic Aptitude Test scores, defenders of the status quo tend to react with derision. They see such criticisms as expressions of "naive romanticism" or" romantic individualism." A child's education, they say, is to be directed by educational professionals, implementing the knowledge they have gained from their study of educational science, that is, knowledge of the conditions required for children's optimal mental growth. Education is not to be left to the subjective intuitions of romantic dreamers with their foolish ideas about children being the best judges of what they need to know or being allowed to do whatever they want to do.

There are, I believe, two things wrong with that response. First, the claims educators have made to scientific knowledge of what children require do not sustain examination. To put the point more strongly, there is no such thing as educational science. When the views that have been offered as scientific are examined closely, they tum out to be not scientific at all but rather a combination of personal taste and simplistic, distorted versions of philosophical theories about how the mind works. Second, the denial of children's individuality is not to be taken lightly. What careful observation of children actually shows is that great harm is done when there is a systematic suppression of a child's interests, values, and idiosyncratic potentials. Indeed, it is the denial of individuality, the idea that everyone must follow some general plan, that is at the core of the failure of the schools.

In brief, defenders of schooling in its present form claim that its programs are arrived at scientifically and are applicable to everyone. I believe that the programs are not arrived at scientifically and are not applicable to everyone. The present work is an attempt to illustrate those points.

Footnotes

James B. Conant, The American High School Today (New York: Signet Books, 1959), p.19.

Horace Mann, Lectures and Annual Reports on Education, ed. Mary Mann (Cambridge, Mass.: Published for the editor, 1867), p.

Ibid., p.220.

Charles Silberman, Crisis in the Classroom (New York: Random House, 1970), p. 10.

1. Is Educational Theory Scientific?

Horace Mann was one of the first educators to claim that the process of formal schooling is based on scientific knowledge of how a child's mind develops. Without that knowledge, he said, one would have no right "to attempt to manage and direct ... a child's soul."

Combe held that the mind consisted of some faculties or "propensities," such as benevolence, combativeness, self-esteem, and veneration. Each of those faculties was located in a particular part of the brain. As the faculty developed, the area of the brain in which it was located got larger, pushing out the skull. Using that "scientific" knowledge, one could cultivate the desirable faculties and suppress the undesirable ones by using an objective method, that is, by measuring the "bumps" on the skull to determine how well the process was proceeding.