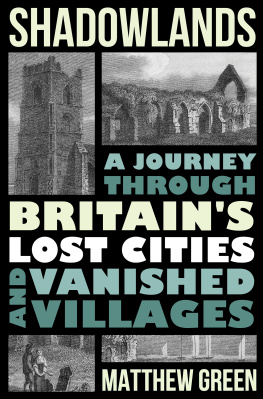

MATTHEW GREEN

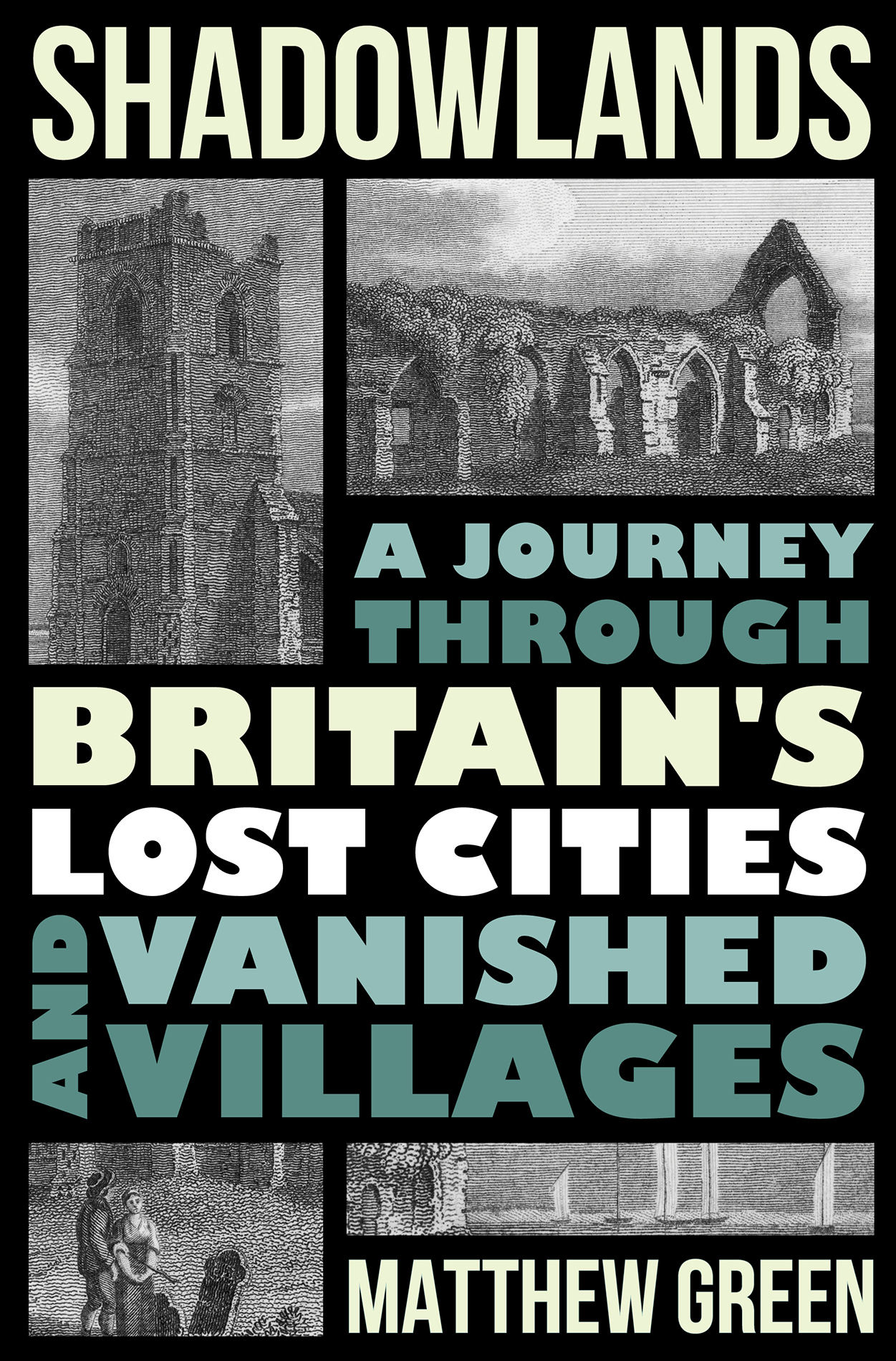

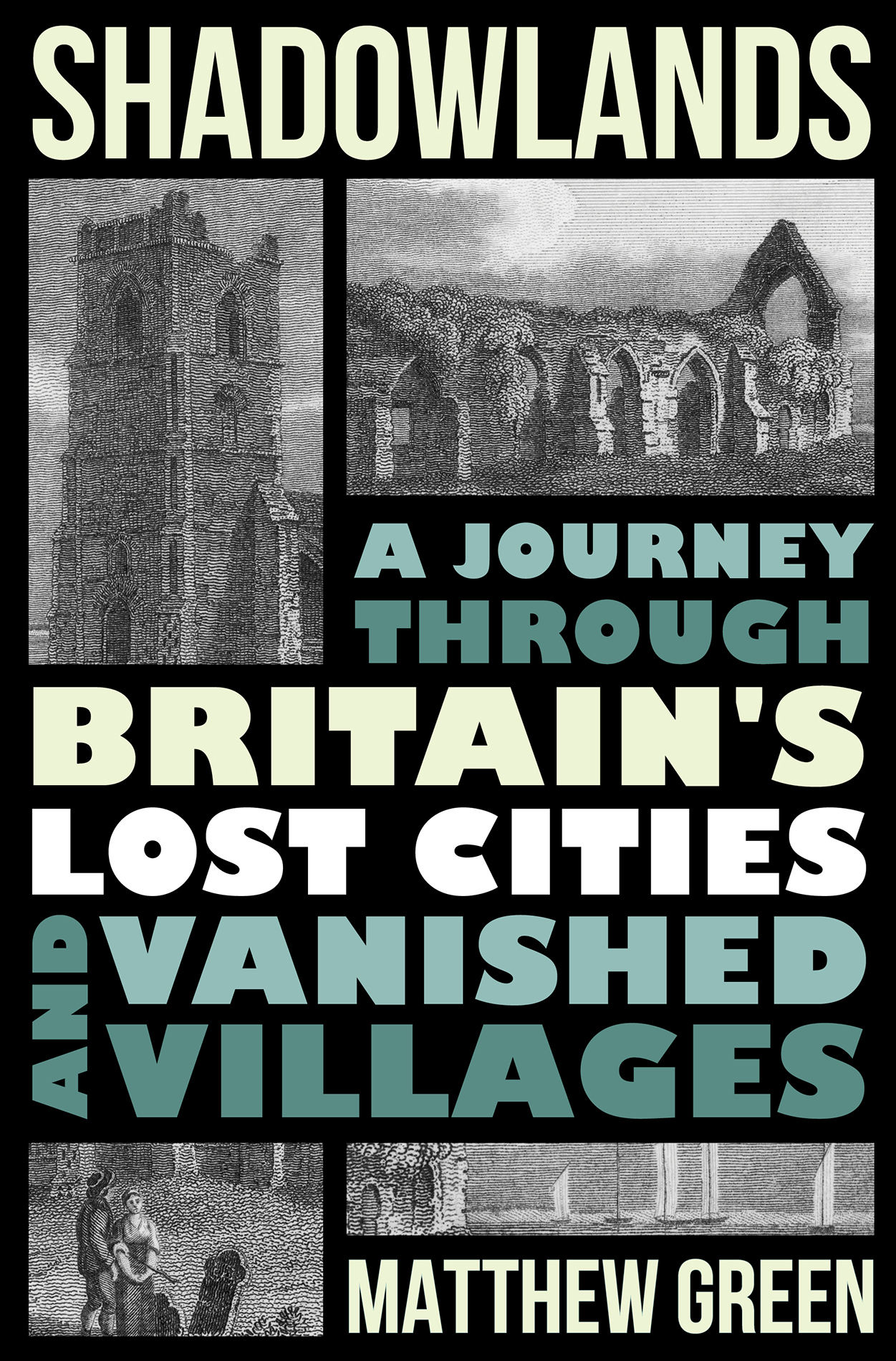

SHADOWLANDS

A Journey Through

Britain's Lost Cities and

Vanished Villages

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

For my father

was instantly poignant, not just prescient of climate change but an emblem too of the turbulent political mood of the day, with the vote to leave the European Union in Britain and the election of Donald Trump in the United States representing a new era of uncertainty: a sense of everything melting down and changing form.

The years that followed would be a time of turbulence in my own life, too; I split up with my wife and lost my father, which contributed to a period of great emotional turmoil and psychological despair. Ambushed by memories, with the past hanging like a pall in the air, the present seemed so thin as to barely to exist at all; the future was too terrifying to contemplate. Could these lost cities I hoped there was more than one provide me with perspectives that would allow me to move forward? The sunken medieval metropolis began to sound like a salutary tale, and I was determined to discover how our country has come to be shaped by absences, just as my life had come to be defined by what was no longer there.

Dunwichs demise was by no means a freak historical occurrence. Britain, as it turned out, was a great reservoir sometimes literally -of vanished places. A map of Britain in 1225 would show thousands of settlements not just villages but towns and cities too that do not appear on todays charts, or which exist only as a shadow of their former selves. Even a 1925 map shows dozens of settlements that lie forlorn and abandoned today. This, then, is the untold story of Britains lost cities, ghost towns and vanished villages, the places that slipped through the fingers of history. From the stone cottages of Skara Brae in Orkney, Europes most complete Neolithic village, to the lost city of Trellech in the Welsh Marches where England dissolves uneasily into its conquered neighbour Wales, the landscape of Britain is scarred with the relics of vanished places, their haunting and romantic beauty so often at odds with the violence and suddenness of their fate. I wanted to dig up not just the physical remains of Britains shadowlands but the extraordinary stories of how those places met their fate, evoking a cluster of lost worlds, animating the people who lived, worked, dreamed and died there, and showing how their disappearances explain why Britain looks the way it does. And I found out just how easy it was for cities, towns and villages to fall foul of the historical process and sink into oblivion. Yet if history had taken an ever-so-slightly different path, its feasible that some of these vanished places might very well still be thriving today.

I wanted to see them with my own eyes, to feel them. I recall my first journey vividly, waiting for eight listless hours in Aberdeen, finally boarding the night ferry to Orkney, standing on the deck, little pellets of rain tearing my face, as the port slowly faded from view and the ship coursed into the glittering black. On board, television sets beamed news into deserted corridors; a lonely cafeteria served meals to passengers who, shuffling gently to their tables, ate chips smothered in ketchup and stared out into the black waves; and, in the heart of the ferry, a cinema played to no one. I embraced the tilting of the boat as sleep came to my pod, before staggering into the cold, sea-sprayed air with wild, remote bells ringing in a charcoal sky. I walked up a dual carriageway towards the city of Kirkwall ahead of my trip to an abandoned Neolithic settlement the oldest in Europe the next day. It was the first of many journeys that would take me to the margins, to the shadowlands of Britain. In time, I would sail to an Outer Hebridean island of rock in the remotest part of the British Isles, peer into a lonely reservoir in the dying light in rural Gwynedd, and roam past ghost churches in Norfolks golden heathland and in the upland splendour of the Yorkshire Wolds.

The remains of disappeared places, wherever they are to be found, are deeply affecting. A priory standing forlorn on a cliff while the rest of the city moulders beneath the grey waves of the North Sea. The former streets and alleys of a plague village, scorched into lonely fields. A village sunk in a reservoir, its slimy carcass revealed in times of drought. A city gate stranded in an overgrown field of nettles. A street in a once-flourishing village now a heap of bullet-riddled ruins. The incongruity between the settlements in their prime and in the quiet misery of their ruin conveys the transience of all earthly things a truth so pat in words yet powerfully, ineffably, manifested in shrunken structures or total absence.

I came to realise that much of this timeless fascination with lost cities stems from their metaphorical and symbolic resonance, whether with Roman Pompeiis artefacts and buildings exquisitely preserved under volcanic ash and pumice for seventeen hundred years, the gold-rush towns of California left to rot in the desert, or, more recently, the inner-city prairies of Detroit. What were once vast monuments of human endeavour look, in their decay, like victims of hubris. Places like these can be soothing and uplifting, too, putting ones own troubles in perspective. Lost in a spiral of self-doubt staring at the battered remains of the church tower in a village wiped out following the Black Death in Yorkshire, I felt able to make peace with that doubt, and persist. The vanished place is a white-washed canvas on to which we can project.

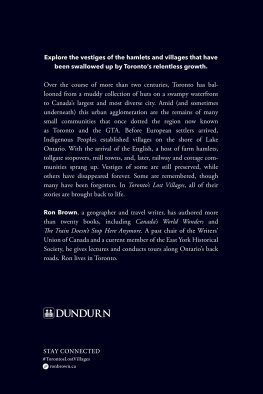

As an author and social historian originally specialising in the history of London, I have always striven to make the past live and live vividly. For almost a decade now, I have been leading immersive whirlwind tours, mainly through the City of London, powered by such things as bitter Muhammedan gruel (seventeenth-century coffee), creator of the worlds happiness (medieval wine) and of course mothers ruin (gin!). These tours are primarily to places and spaces that no longer exist: to the convivial, candlelit coffeehouses of the eighteenth century; medieval anchorite cells where living men and women were willingly entombed in a tiny, coffinlike space to bring them closer to God; Elizabethan bear pits and Victorian pornography shops. These are all places that, though their original buildings have long since crumbled away, helped shape the mentality of each successive age, and left their mark on the social life of the city, as well as the odd mournful remain. And so from lost London to lost Britain, I sought to chart Britains shadow topography, highlighting the fragility and fluidity of our twenty-first-century map, and revealing the continued impact of these unseen places on both the landscape and imagination of Britain.

It felt urgent to do this now, as the planet heats and parts of society are ravaged by the coronavirus pandemic. As is well known, if carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions are not dramatically lowered within the next thirty years, catastrophic heatwaves, floods, storms, other extreme weather events, famines and social unrest stemming from refugee crises and a global fight for scarce resources, not to mention the extinction of entire animal, insect and plant species, will wreak havoc upon our land. Many of Britains coastal communities are already vanishing into the sea, and Global warming is far from a new phenomenon. My itinerary of destruction includes two medieval cities that were swept into the sea by ferocious sea storms that coincided with the Medieval Warm Period, which saw temperatures and sea levels rise in western Europe, leading to the loss of hundreds of towns, villages, parishes and even islands between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries, and over 1.5 million lives. Medieval climate change was not man-made but the fates of the two sunken medieval cities encountered here, Old Winchelsea and Dunwich, nonetheless serve as an awful premonition of what lies ahead for some of our own homes as a direct result of climate change that

Next page