The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52969-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52972-1 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52986-8 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226529868.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Epp, Derek A., author.

Title: The structure of policy change / Derek A. Epp.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: lccn 2017047640 | isbn 9780226529691 (cloth : alk. paper) | isbn 9780226529721 (pbk : alk. paper) | isbn 9780226529868 (e-book)

Subjects: lcsh: Policy sciencesUnited States. | Public administrationUnited States. | United StatesPolitics and government.

Classification: lcc h97 .e76 2018 | ddc 320.60973dc23

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017047640

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my parents

This book would never have been possible without the guidance of Frank Baumgartner. The best decision I made as a graduate student was asking Frank to be my adviser. I entered graduate school knowing nothing about the profession, but I was tipped off that Frank would be a good choice for adviser by a wall in his office that is covered with teaching accolades. He lived up to his reputation. Long ago, Frank established himself as a terrific political scientist. What makes him a good mentor is that he is a terrific personthoughtful, generous, and unfailingly supportive. Thank you, Frank.

I was fortunate to have a lot of good mentors early in my career. Thank you, Jim Stimson, Virginia Gray, Tom Carsey, Chris Clark, Mike MacKuen, and Bryan Jones. Together with Frank, you taught me almost everything I know about political science; most important, that it is best practiced as a collective enterprise, in which we work together to think through new ideas.

This book benefited tremendously from three reviewers who read the entire manuscript. Thank you, Chris Wlezien, Chris Koski, and Peter Mortensen. Your reviews were top-notch in every respect: intellectually challenging and critical, but always constructive. Dedicated, thoughtful reviewers are such a luxury, and I am indebted to your insights. Thanks as well to Chuck Myers for your guidance and advice throughout the process.

I would like to thank all the faculty and staff at the Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College. In particular, thanks to Ron Shaiko for believing in me and hiring me for what is without any doubt the very best postdoc available in the profession. Your pursuit of excellence in pedagogy and your insistence that a successful department makes positive contributions to the local community was inspirational. Thanks to Jane DaSilva for being so kind and supportive. Thanks to Herschel Nachlis, Julie Rose, Sean Westwood, Jeff Friedman, Kathryn Schwartz, and David Cottrell for much-needed distractions from writing.

I thank Greg Wolf, Amanda Grigg, John Lovett, and the rest of my graduate student colleagues. I am proud of what we accomplished together during our time at Chapel Hill. I thank Brian Godfrey, my excellent and very capable research assistant. I thank Erica. Most of all, I would like to thank my wonderful parents.

The Rise and Fall of NASAs Budget and Other Instabilities

President Eisenhower was dismissive. Having been briefed on the R-7 Semyorka, the Soviet Unions powerful new rocket, he was well aware that the USSR was capable of putting a satellite into orbit. In a press conference shortly after Sputniks 1957 launch, Eisenhower attempted to reassure the American people, conceding that the Soviets had put one small ball in the air, but quickly adding I wouldnt believe that at this moment you have to fear the intelligence aspects of this. Later, his chief of staff, Sherman Adams, likened the satellite launch to one shot in an outer-space basketball game. What the Eisenhower administration had underestimated was the deep, almost visceral, reaction Americans had to news of the satellite. It was disconcerting on two levels. First, it appeared inconsistent with the prevailing notion that the Soviet Union was a technological backwater, incapable of matching the United States economic or scientific prowess. Second, people were skeptical of Eisenhowers assurance that they had nothing to fear. Radio stations had broadcast the satellites signal as it traveled over America, and it seemed obvious that something that so easily violated transnational boundaries presented security risks. Edward Teller, the famous nuclear arms proponent, warned that America has lost a battle more important and greater than Pearl Harbor. The public seemed inclined to agree with these ominous sentiments.

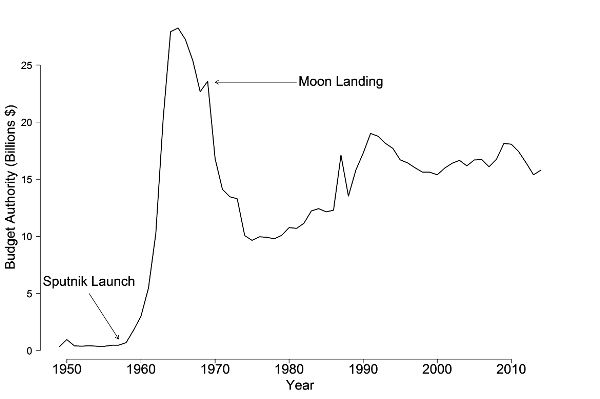

During the ensuing media frenzy, the Eisenhower administration bowed to public pressure and rethought its initial restraint. It appeared that a major undertaking was needed to reassure the public that America, although second out of the gate, was not going to lose the space race. Change came quickly. Within a year, Eisenhower signed legislation creating the Advanced Research Project Agency and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and passing the National Defense Education Act, which allocated billions of dollars to helping students go to college to get degrees in math and science. By 1961, when President Kennedy gave his famous speech about putting an American on the moon, US outlays toward spaceflight and technology, a budget category that scarcely existed in the early 1950s, had already increased tenfold from 1957 levels. Altogether, from the launch of Sputnik in 1959 to the moon landing in 1969, US spending on spaceflight increased by almost 5,000 percent.

the Soviet Union, no matter the stakes, the sacrifices, or the nature of the competition.

Figure 1.1. Annual budget authority for spaceflight

Note: Budget authority is presented in constant 2012 dollars.

Eventually, NASA turned that string of failures into a series of fantastic successes. In 1969, having successfully planned and executed a manned trip to the moon, NASAs directors had good reason to feel optimistic about Americas future in space. The next step was the Space Transportation System, which would feature a number of reusable space shuttles that could reliably move astronauts in and out of orbit, a series of space stations leading to a lunar base, and eventually a trip to Mars. Few at the time would have guessed that spending on spaceflight had peaked in 1965, four years before Apollo 11 put astronauts on the moon. Much like President Eisenhower, NASAs directors had seriously misjudged public sentiment. They had hoped that scientific exploration of space was the idea motivating Americas pursuit of the moon. This was partly true, but the overriding idea was one of fear of and competition with the Soviets. With the space race won decisively for America, enthusiasm for costly space adventures rapidly diminished. The price NASA paid for their success was a 50 percent reduction in their operating budget in the early 1970s. Policy makers had envisioned a trip to the moon, NASA had delivered, and that was as far as the vision went. Although reusable space shuttles were developed in the early 1980s, by 2011 the fleet was grounded due to safety concerns and high operating costs. Today, NASAs capacity to put people in orbit is less than it was in the 1960s, and, ironically, American astronauts currently buy passage to space on board Soyuz, spacecraft developed and operated by NASAs Russian counterpart.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).