THE WORKS OF HAROLD J. LASKI

Volume 14

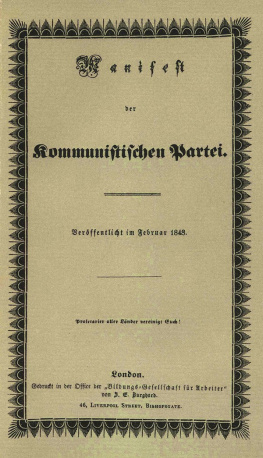

COMMUNIST MANIFESTO SOCIALIST LANDMARK

First published in 1948 by George Allen and Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2015

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1948 George Allen and Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-81912-2 (Set)

eISBN: 978-1-315-74273-1 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-138-82222-1 (Volume 14)

eISBN: 978-1-315-74256-4 (Volume 14)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1948

SECOND IMPRESSION 1951

THIRD IMPRESSION 1954

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1911, no portion may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiry should be made to the publisher.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

JARROLD AND SONS LIMITED, NORWICH

Contents

IN presenting this centenary volume of the Communist Manifesto, with the valuable Historical Introduction by Professor Laski, the Labour Party acknowledges its indebtedness to Marx and Engels as two of the men who have been the inspiration of the whole working-class movement.

The British Labour Party has its roots in the history of Britain. The Levellers, Chartists, Christian Socialists, the Fabians and many other bodies, all made their contributions, and the British Trade Unions made it possible to carry theory into practice. John Ball, Robert Owen, William Morris, Keir Hardie, John Burns, Sidney Webb, and many more British men and women have played outstanding parts in the development of socialist thought and organisation. But British socialists have never isolated themselves from their fellows on the continent of Europe. Our own ideas have been different from those of continental socialism which stemmed more directly from Marx, but we, too, have been influenced in a hundred ways by European thinkers and fighters, and, above all, by the authors of the Manifesto.

Britain played a large part in the lives and work of both Marx and Engels. Marx spent most of his adult life here and is buried in Highgate cemetery. Engels was a child of Manchester, the very symbol of capitalist industrialism. When they wrote of bourgeois exploitation they were drawing mainly on English experience.

The authors were the first to admit that principles must be applied in the light of existing conditions, but even the detailed programme they put forward is of great interest to us. Abolition of private property in land has long been a demand of the Labour movement. A heavy progressive income tax is being enforced by the present Labour Government as a means of achieving social justice. We have gone far towards abolition of the right of inheritance by our heavy death duties. Centralisation of credit in the hands of the State is partially attained in the Bank of England Act and other measures. We have largely nationalised the means of communication while extending public ownership of the factories and instruments of production. We have declared the equal obligation of all to work. We are engaged in redressing the balance between town and country, between industry and agriculture. Finally, we have largely established free education for all children in publicly-owned schools. Who, remembering that these were demands of the Manifesto, can doubt our common inspiration?

Finally, a word about the Introduction. In his preface to the 1922 Russian edition of the Manifesto, Ryazanoff pointed out that a commentary would need to do three things:

To give the history of the social and revolutionary movement which called the Manifesto into life as the programme of the first international communist organisation.

To trace the genesis, the source, of the basic ideas contained in the Manifesto, to show their place in the history of thought, to bring out what was new in the philosophy of Marx and Engels, what differentiates them from earlier thinkers.

To indicate to what extent the Manifesto stands the test of historical criticism and how far it needs amplification and correction in certain points.

Ryazanoff did not produce such a massive work; Professor Laski has gone far towards it, and we look forward to the further material that he promises. Since his publication of Communism, twenty years ago, he has been the foremost English authority on the subject. It is unnecessary to do more than commend to all the present scholarly Introduction which he has presented to the Labour Party for this special centenary edition of the Manifesto.

IN the spring of this year the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party decided to celebrate the centenary of the Communist Manifesto by the publication of a new edition with an historical introduction and illustrative material. At their request I undertook this task.

What is now published is only the Manifesto itself and the Historical Introduction. In the present circumstances it has seemed better to postpone the publication of the illustrative material, and a considerable body of notes, until the paper situation is less difficult; and I have also refrained from printing the very considerable annotated bibliography I have prepared. I hope these will appear in a separate pamphlet at a later date.

It is only necessary to add that, for English readers, by far the best lives of Marx and Engels are those by F. Mehring and Gustav Mayer respectively. They are of irreplaceable value in seeking to put the Manifesto in its full biographical perspective.

H.J.L.

London, 3 November 1947

THE Communist Manifesto was published in February, 1848. Of its two authors, Karl Marx was then in his thirtieth, and Friedrich Engels in his twenty-eighth, year. Both had already not only a wide acquaintance with the literature of socialism, but intimate relations with most sections of the socialist agitation in Western Europe. They had been close friends for four years; each of them had published books and articles that are landmarks in the history of socialist doctrine. Marx had already had a stormy career as a journalist and social philosopher; he was already sufficiently a thorn in the side of reactionary governments to have been a refugee in both Paris and Brussels. Engels, his military service over, and his conversion to socialism completed after he had accepted the view of Moses Hess that the central problem of German philosophy was the social question, and that it could only be solved in socialist terms, had already passed nearly fifteen months of his commercial training in his fathers firm in Manchester by the end of 1843. He had gained a deep insight into English conditions. He had come to understand the meaning of the conflict between the major political parties, the significance of Irish nationalism, then under the leadership of Daniel OConnell, and all the stresses and strains within the Chartist Movement; he appreciated the meaning of Chartism, and he had joined its ranks. He realised how great had been both the insight and the influence of Robert Owen. He had been an eager reader of the