Table of Contents

For T.J.

I pondered all these things, and how men fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.

William Morris,A Dream of John Ball

The best story Ive ever heard about The Communist Manifesto came from Hans Morgenthau, the great theorist of international relations who died in 1980. It was the early seventies at CUNY, and he was reminiscing about his childhood in Bavaria before World War I. Morgenthaus father, a doctor in a working-class neighborhood of Coburg, often took his son along on house calls. Many of his patients were dying of TB; a doctor could do nothing to save their lives, but might help them die with dignity. When his father asked about last requests, many workers said they wanted to have the Manifesto buried with them when they died. They implored the doctor to see that the priest didnt sneak in and plant the Bible on them instead....

As the nineties end, we find ourselves in a dynamic global society ever more unified by downsizing, de-skilling, and dreadjust like the old man said....At the dawn of the twentieth century, there were workers who were ready to die with The Communist Manifesto. At the dawn of the twenty-first, there may be even more who are ready to live with it.

Marshall Berman,Unchained Melody

Preface and Acknowledgements

There are dozens of editions of The Communist Manifesto currently in printdo we really need another? I think a combination of three things makes this edition distinctive and worthwhile. First, it is edited by someone who is sympathetic to Marxs general political perspective and views the Manifesto as more than an interesting historical relic. Second, it is aimed specifically at both students reading the Manifesto for the first time and young political activistsfighting against corporate globalization, war, environmental destruction, and all forms of oppressionwho want to know whether Marxs ideas are useful guides for them today. Third, it includes not just an introduction and a few notes on the text, but a full set of annotations, as well as study and discussion questions, an afterword on the contemporary relevance of the Manifesto, and a glossary. Several of the extant editions have one or even two of these features, but none has all three. The only other fully annotated version of the Manifesto in English that I am aware of is Hal Drapers The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto (1994). Drapers book is an important resource, which I often found valuable in writing my own commentary, but it is both difficult to obtain and written at a level of scholarly detail that most new readers of the Manifesto would find intimidating. While Drapers annotations contain many penetrating insights, it is often hard to see the forest for the trees. In what follows, I hope the forest remains fully visible.

Thanks are owed to many people. Anthony Arnove and Julie Fain encouraged me to take on this project and prodded me to finish it. Lance Selfa, Snehal Shingavi, and, in particular, Paul DAmato gave me helpful comments on earlier drafts. Mikki Smith and Dao Tran did the vital jobs of copy editing and proofreading. Eric Ruder designed the striking cover. Alan Maass did amazing work on the books layout. Special thanks to Kim Rabuck for her support, advice, and patience. My gratitude to everyone. Needless to say, any remaining mistakes are my own.

P.G.

June 2005

INTRODUCTION

Historys Most Important Political Document

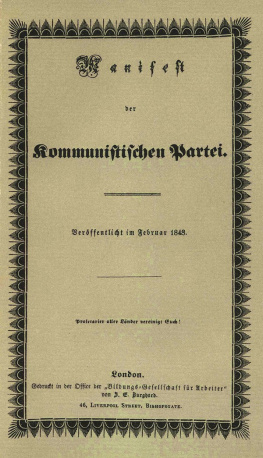

The Communist Manifesto was first published in February 1848. Why is it still worth reading a book that was written so long ago? One answer to that question is that the authors of the

Manifesto, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, describe a world that is still recognizably our own. In the

Manifesto they call it bourgeois societyin other words, a society in which the bourgeois class (defined by Engels as the class of modern capitalists, owners of the means of social production, and employers of wage labor) is dominantbut later Marx himself would popularize the name by which it is now commonly known: capitalism. Much has changed since the mid-nineteenth century, but like Marx and Engels, we still live in a capitalist society. When they were writing, capitalism was established in relatively few places, most importantly in parts of western Europe and North America, but Marx and Engels envisioned that capitalism would eventually become a global system. Today nearly every area of the world is part of a single capitalist economic system. Precisely because Marx and Engels lived at a time when modern capitalism was young, they were able to analyze the system in a way that still seems to many to capture its essential features and its core dynamic. Here, for instance, is their dazzling description of the incessant change that capitalism brings in its wake:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life and his relations with his kind. (I.18)

Change can be exhilarating, and Marx and Engels praise the way in which capitalism has shattered narrow horizons and produced technological marvels. But they also see capitalism as a system that is increasingly running out of control, a system that concentrates wealth and power in the hands of a small minority, creates huge pools of poverty, turns life into a daily grind that prevents most people from fulfilling their potential, and experiences frequent and enormously wasteful economic crises. Capitalist development is also highly destructive of the natural environment, and economic competition between capitalist states often leads to military confrontation and war. The only solution to these potentially devastating problems, according to the Manifesto, is the abolition of capitalism itself and its replacement by a system in which the majority of the population democratically control societys economic resourcesin other words, genuine communism. Marx and Engels proposal is, to say the least, controversial. However, a strong case can be made that the problems they diagnose have not disappeared. If the roots of these problems run as deeply as Marx and Engels contend, then radical action remains necessary. That, perhaps, is reason enough to ponder the alternative they advocate.