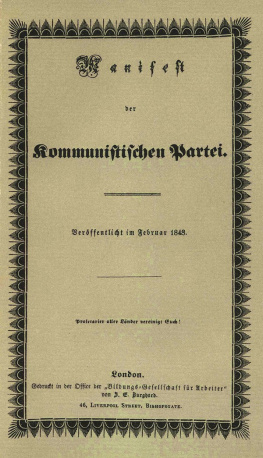

Manifesto of the

Communist Party

A Modern Edition

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

With an Introduction by Tariq Ali

First published by Verso 2016

Introductions Tariq Ali 2016

Notes to the Manifesto Eric Hobsbawm 1998, 2016

The April Theses translation Bernard Isaacs 1964, 2016

Letters from Afar translation M. S. Levin, Joe Fineberg et al.

Manifesto of the Communist Party first published in English 1848;

this translation first published 1888

The April Theses [The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present

Revolution] first published in Pravda no. 26, 7 April 1917; published in

English in V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 24, 4th ed. (Moscow 1964)

Letters from Afar published in English in Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 23

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-690-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-689-2 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-691-5 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Bembo by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

Introduction to the

Communist Manifesto

In Brechts famous parable of the Tailor of Ulm this sixteenth-century German artisan had been obsessed by the idea of building a device that would allow men to fly. One day, convinced that he had succeeded, he took his contraption to the Bishop and said, Look, I can fly. Challenged to prove it, the tailor launched himself into the air from the top of the church roof, and naturally, ended up in smithereens on the paving stones below. And yet, Brechts poem suggests: a few centuries later men did indeed learn to fly.

Lucio Magri, The Tailor of Ulm

The Manifesto is the last great document of the European Enlightenment and the first to register a completely new system of thought: historical materialism. As such it marks both a continuation and a break. Infinitely more radical than its French and American predecessors, written at a time when the impact of a huge political defeat was beginning to wear off, it was the product of two young German minds, both intellectuals in their twenties and both schooled in the Hegelian philosophical tradition that dominated Berlin and other German universities during the first half of the nineteenth century. This text was a major turning point in the revolutionary theory and practice of the last two centuries, insisting, as it does, that revolution is the inevitable outcome of capitalism in modern industrialized societies.

Occasionally, philosophical debates in Germany left a mark much uglier than the duelling scars of the era. It was the evolution of philosophy that resulted in the birth of a new left radical milieu in which Marx and Engels played a significant role. All their texts, especially this one, should be studied in the social, economic and philosophical context of the period in which they were written. To treat them as devotional tracts is to debase both meaning and method and, in the case of the Manifesto in particular, to render them harmless. The prescriptions and predictions are obviously outdated today, and capitalism itself, despite the triumph of 1991, appears more like a nervous disorder rather than an organism capable of taking humanity forward. We desperately need a new manifesto to meet the challenges of today and those that lie ahead, but till that time (and even afterwards) there is much to learn from the method, the lan and the language of this one.

Politics was decisive in pushing forward the further radicalization of the young German intelligentsia of the nineteenth century. There was no option left. Either they joined him or they had to move beyond Hegel. The period opened up by the French Revolution in 1789 had come to an end with Napoleons defeat at Waterloo in 1815. The Congress of Victors convened in Vienna later that year had agreed a map of Europe and discussed mechanisms through which dissent could be controlled and crushed. The Vienna Consensus would be policed by Russia, Prussia and Austria with the British Navy as an ever-reliable backdrop, a weapon of last resort. The triumph of reaction fuelled the retreat on the intellectual front. Hegel, the theorist of permanent mobility, insisted that history was never static, itself the result of a clash of ideas, a dialectic where past and present determined the future. This history, he insisted, was inevitable, unpredictable and, most importantly, unstoppable. Shaken by the defeat at Waterloo, he now accepted the end of history. The once dynamic world-spirit had cast aside Napoleons greatcoat, hat and the tricolour in favour of the steel helmets and the eagle of the Prussian Junkers. Field Marshal Blcher had defeated the upstart Corsican. A triumphant Prussia could well be a model state, confining the historical process to an eternal mausoleum. It was not to be.

Apart from all else, even though 1815 imposed a silence on the French Revolution, its social and juridical achievements were essentially maintained: the feudal estates were not restored to their former lords. The liberating impact of the Revolution lived on in the memories of the common people and not just in France. Rousseaus maxim was not forgotten: You are lost if you forget that land belongs to no one and its fruits belong to everyone.

Some of Hegels most gifted pupils and followers, including our two authors, followed events in France in minute detail. They were aware of the Conspiracy of Equals that had followed the Revolution. The attempt to establish a plebeian Vendee had been defeated and its commonist/communist planners executed. Franois Babeuf (who had adopted the pseudonym Gracchus) had stabbed himself to escape execution on 26 March 1797. These vibrant histories as well as those of the Revolution itself were eagerly devoured by young radicals in Germany and elsewhere. Secret societies, underground work, resistance, acts of individual violence were commonplace. Debates on what happened to the second revolution in France after Robespierres defeat by the Thermidorian Reaction never ceased. It was, after all, the language of the radicals, repudiated by the Directory and Napoleon, that anticipated the demands that would later envelop the continent: universal suffrage, separation of church and state, some redistribution of wealth.

That is why, despite the break with post-1815 Hegel, the German radicals, finding his conclusions deficient, carried on using important elements of his method to investigate the world. Intellectual fertility did not end with the masters retreat, and its offspring increased both in volume and content. Feuerbach had turned Hegel on his head, refuting the notion that ideas determined being. He insisted on the opposite: it was being that determined consciousness. Another precocious Left-Hegelian enhanced the critique further. Marx articulated social and class differences that existed within society as a whole. Might these, he enquired, have something to do with the difference in status between the King of Prussia, a Moselle peasant and a factory worker? What was it that produced the ensemble of social relations that highlighted the difference between one class and another? It was this that needed to be further investigated and mapped in order to understand how the world functioned. It was not enough to denounce property as theft or to state that humans were a product of their environment. Who could have fantasized that the world-spirit, expelled from its homeland by rampant reaction, would, thanks to Marx and Lenin, end up in Petrograd and Moscow and later travel to other continents and mingle with native spirits?