Table of Contents

Karl Marx (18181883) was born in Trier to a German Jewish family that had converted to Christianity. As a student he was influenced by Hegels dialectical philosophy but later reacted against his mentors idealism and turned instead to the then new socialist movement. The Communist Manifesto (utilizing drafts by his friend Friedrich Engels) was written in Brussels for a German emigr society, the Communist League. After taking part in the failed revolutions of 1848, Marx fled to London, where he and his family lived in poverty alleviated only by Engels financial help. For some years, Marx was a London correspondent for a New York newspaper. He spent most of his time, however, researching in the British Museum to document his theories of class struggle and the internal contradictions undermining capitalism. His works include The Poverty of Philosophy, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, The German Ideology , and A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.

Friedrich Engels (18201895) was born in Germany, the son of a textile manufacturer. After his military training in Berlin, he became an agent of his fathers business in Manchester and immersed himself in Chartism and the problems of the new urban proletariat created by the industrial revolution. In 1844, the year he met Karl Marx, he wrote The Condition of the Working Class in England. The pairs ideas were incorporated into The Communist Manifesto. After Marxs death, Engels continued his work on Das Kapital and completed it in 1894, a year before his own death. He also wrote The Peasant War in Germany, The Origin of the Family, and Socialism, Utopian and Scientific.

Martin Malia did his undergraduate work at Yale and earned his PhD at Harvard. He has spent most of his teaching career at the University of California at Berkeley. His principal works include Alexander Herzen and the Birth of Russian Socialism, 18121855, The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 19171991, and Russia Under Western Eyes: From the Bronze Horseman to the Lenin Mausoleum.

Stephen Kotkin teaches history and international affairs at Princeton. His books include Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse 19702000 and Uncivil Society: 1989 and the Implosion of the Communist Establishment. He formerly directed Princetons Russian and Eurasian studies program (19962009) and served as the regular business book reviewer for the New York Times Sunday Business section (20062008). He founded and runs Princetons Global History initiative.

INTRODUCTION

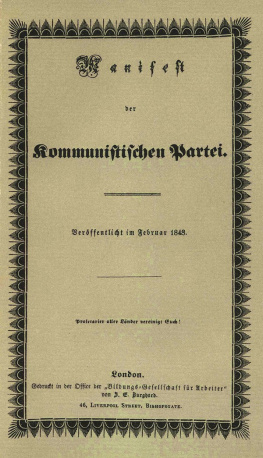

When the Manifesto of the Communist Party was published on the eve of the February Revolution of 1848 in Paris, its principal author, Karl Marx, then barely thirty, was convinced that the triumph of his cause was imminent: the proletariat was about to rise to the position of ruling class in France, England, and Germany, and its victory worldwide was only a matter of time. One hundred and fifty years later, of course, these fantasies have proved to be just that. Yet it took almost that long for this to be demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt; and meanwhile the Communist Specter he invoked in truth never ceased to haunt the world.

The sesquicentennial of the Manifesto, then, raises two questions: why did its prophesies appear so alluring to so many for so long; and why did they ultimately prove to be so hollow, even perverse? Since the specter has now been cast on the ashheap of history (where Trotsky consigned Bolshevisms adversaries in October 1917), the answer is best pursued by tracing its quite unexpected migrations from the advanced West to the backward East, and from the revolutionary springtime of 1848 to the twilight of utopia-in-power in 198991.

I: THE PATH TO THEMANIFESTO

It is the convention to explain Marxisms founding document as a response to the human costs of the Industrial Revolution; and this is indeed part of the story. But just as important is the conjunction of the new market society with the ideological heritage of the French Revolution: nascent industrialism, after all, was at its most advanced in England, whereas the epicenter of emerging socialism was France. It is less often emphasized, however, that the variant of socialism the Manifesto called Communist was produced by a pair of intellectuals, and that they hailed from then-preindustrial Germany.

Of course, Marx himself pointed out that his system was a synthesis of British political economy, French socialism, and German philosophy. Even so, until the discovery of his early manuscripts in the 1930s, it did not become clear that the German element of his amalgam was not only the first in time, but the most basic in substance.

Briefly put, classical German philosophy was an Idealism in which the world conformed to mind (in Kants phrase), whereas the Anglo-French Enlightenment against which it was reacting was an empiricism in which mind conformed to the world. With Hegel, moreover, philosophy for the first time became historical in its essence, and truth was now a perpetual unfolding rather than a set system. In general terms, Marx sought to make this metaphysical historicism once again empirical by transforming it into a social science in the Anglo-French manner, or what he called historical materialism.

As a Left-Hegelian, Marxs starting point was Hegels vision of history as the progression of rationality through dialectical negation and transcendence to absolute self-consciousness, a culmination which also signifies human freedom. Marx then assigned to this process the leveling goals and the commitment to class struggle of revolutionary French socialism. Finally, he made Hegels conceptual logic materialistic by recasting it in a critical adaptation of the economic categories of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Yet in the resulting system, the key componentthe element which made it a system and gave it its allurewas the overarching logic of German philosophy.

Marx effected this synthesis during his first emigration, in Paris and Brussels, between 1843 and 1846. Simultaneously, he began his collaboration with Engels, who brought to the mix first-hand acquaintance with advanced English industrialism. And so, by 1846, in The German Ideology (their joint settling of accounts with Hegelianism, unpublished until 1932) all the essential elements of future Marxism had been fused.

At the same time, the pair were engaged in organizing migr German workers in Paris, Brussels and London to prepare for an expected German revolution. In 1847 a secret society of such workers, using the ominous name Communist League, commissioned Marx and Engels to write a programmatic statement. Seizing the occasion, Marx condensed his new theory into shock phrases as a revolutionary catechism. The result was that marvelously timed masterpiece of propagandistic literature which was the Manifesto of 1848.

The Manifestos aim was to promote a Second Coming of the French Revolution in socialist guise, an aim common to a range of radical sects of the 1840s. The route to their ambition ran as follows.

The revolution of 178993 had for the first time in history posed the question of democracy in its modern sensethat is, a polity founded on the proposition that all men, simply by virtue of being human, are equal before the law and endowed with full rights of participation in government. These principles are summed up as the rights of man and the citizen and universal suffrage. The events of 1789 did not, of course, succeed in institutionalizing universal (manhood) suffrage democracy; but this is not to say it failed, as is often averred. It had accomplished the epochal feat of mortally wounding Europes millennial