U.S. Foreign Policy, Women, and Saudi Arabia

So there are these tensions between what the real purpose of foreign aid is: Is it to do development or is it a tool of the geostrategic interests of the United States?

Andrew Natsios, former USAID administrator

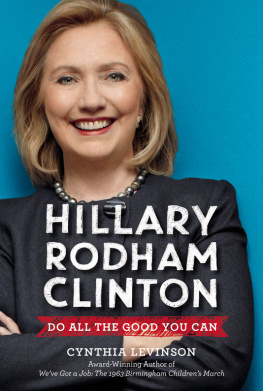

For proponents of the Hillary Doctrine, no irony was more cruel than seeing Secretary of State Hillary Clinton smiling broadly in her trademark pantsuit as she walked the red carpet from her plane on the tarmac in Riyadh with the Saudi foreign minister, Prince Saud al-Faisal, in February 2010.

It brought to mind an incongruity no less extreme than if Frederick Douglass had been appointed ambassador to the Confederacy and found himself sipping tea and making small talk with Nathan Bedford Forrest. For, to be sure, in Saudi Arabia the subordination of women is as finely calibrated as was slavery in the antebellum South. The question of how Hillary Clinton could so seemingly brush her own doctrine to one side in this caseostensibly in the name of national interestis a crucial one.

The either/or vision of foreign aid and diplomacy described by Natsios in the opening quote of this chapter suggests that U.S. foreign policy officials have viewed womens rights as orthogonal to national security. To these officials, national interests and womens interests occupy different planes entirely, and national interests are viewed as the higher plane. This has played out most vividly with reference to Saudi Arabia and its colonization of Yemen, and in this chapter we will explore whether that stance represents a necessary accommodation to reality.

A Gulag for Women: Saudi Arabia and the Export of Islamic Extremism

One day in 2012, Saudi Arabias Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice made a public announcement. The men of the committee will interfere to force women to cover their eyes, intoned spokesman Sheikh Motlab al-Nabet. Especially, he added, the tempting ones. And then, perhaps a little defensively, [We] have the right to do so.

Especially the tempting ones? Well!

The Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, otherwise known as the mutaween or religious police, has been enforcing moral standards in the kingdom since 1940. Although this Orwellian goon squad, dressed in gold-embroidered muslin and carrying wooden staves, routinely rounds up anyone whose behavior is deemed morally suspect, it reserves special venom for women and girls, who are routinely beaten, lashed, and thrown in jail for infringements, real or imagined, of the sexual code of conduct.

Saudi Arabia ranks 145th of 158 countries in the U.N. Development Programmes Gender Inequality Indexmaking it among the worst countries in which to be born female despite its considerable oil wealth.

While Saudi Arabias maternal mortality rate is similar to that of the United States, child marriage is not uncommon because there is no legal minimum age of marriage. Indeed, the media has highlighted a number of notorious child marriage cases, such as when an eight-year-old girl requested the courts in May 2009 to grant her a divorce from her fifty-year-old husband. Consent in marriage is clearly not required from the bride. And in a slightly surreal twist, in Saudi Arabia, a woman need not even be present for her own marriage, as long as her male guardian and her groom agree.

Complicating matters is that Saudi Arabia has no written criminal code. This vacuum puts human rights activists and women at considerable risk because in the absence of written law, Sharia is applied capriciously depending on the geographic location, gender, wealth, reputation, and kinship ties of both accused and plaintiff.

Nevertheless, in 2011, Saudi women finally gained the right to vote and to run in municipal electionsbeginning in 2015. Today, 20 percent of the Kings Consultative Council (Majlis as-Shura) is also made up of women.

It is a puzzling set of ill-fitting pieces, to be sure.

Mobility is one of the most vexing problems facing Saudi women. Women are forbidden to drive (apparently it would hurt their ovaries), or go on a picnic. They cannot travel outside the country nor marry a man of their choosing without the permission of the ubiquitous male guardian.

Gender segregation is extreme. Because of the cultural interdictions against unrelated men and women occupying the same location at the same time, and despite the significant rise in female labor force participation over the past decade, only 17.7 percent of women work outside of the home, compared to 74.1 percent of all males. Eleanor A. Doumato, a professor at Brown University, reports:

One crime for which women are especially targeted is khulwa (the illegal mixing of unrelated men and women), which can occur whether men and women are dining together in a restaurant, riding in a taxi, or meeting for business.... Women are prohibited from most ministry buildings and discouraged from walking along public streets or attending mosques except at pilgrimage.... The public spaces in Saudi Arabia that are intended for the enjoyment of the general public, such as parks, zoos, libraries, museums, and the national Jinadriyah Festival of Folklore and Culture, are also segregated by hours of access, with men allocated the greater number and most convenient time slots.... Prohibited from driving themselves, unable to afford private taxis or cars, and faced with a lack of accessible public transportation, working women are often forced to walk on the streets, where they may be apprehended by the religious police on accusations of soliciting sex.

The watchful eyes of male relatives and the dreaded mutaween circumscribe womens every movementso much so that in a cable to U.S. diplomats, Wajeha al-Huwaidera Saudi womens rights activist who recently challenged the ban on female driversdescribed the country as the worlds largest prison for women.

Perhaps the most telling example of the extremes to which Arab authorities are determined to enforce their grim code occurred in 2002. It was the middle of the night when a blaze broke out in a girls school in Mecca. Firefighters arrived on the scene as eight hundred girls fled for their lives. Also in attendance was the mutaween. As it turned out, they were not there to help save the girls but to prevent them from leaving because they were not wearing their abayas.

The school was locked at the time to ensure the full segregation of the sexesalthough male students are not similarly imprisoned. The father of one of the dead girls later told a news outlet that the school watchman even refused to open the gates to let the girls out, while the Saudi Gazette quoted witnesses as saying that the mutaween had warned, it is a sinful [sic] to approach them.

Fifteen girls died that night because police forced them back into the inferno. Apparently, the police deemed it preferable for schoolgirls to be immolated alive than to risk offending societal norms of modesty by appearing in public improperly attired.