Preface

When the powers and prerogatives of Congress are discussed, the power of the purse is usually mentioned as the most formidable control exercised by Congress. Alexander Hamilton referred to it as a most complete and effective weapon.1 Despite the fact that the appropriations process is at the heart of the spending power, little analysis has been attempted of a crucial type of appropriations supervisionnonstatutory control operating through hearings, committee reports, floor debates, and informal meetings.

During this century extralegal appropriations techniques have increased markedly in frequency and significance. In 1943 Arthur MacMahon observed that there had been a significant change of emphasis in the Congressional attitude toward administrative discretion and its control.2 He asserted that the complex tasks government fulfills in the twentieth century require administrative flexibility, and consequently appropriations control through the detailed character of the statute is in many instances unfeasible. MacMahon concluded: The weight is no longer on the initial insertion of statutory detail or upon judicial review. Rather the legislative body itself seeks to be continuously a participant in guiding administrative conduct and the exercise of discretion. The cords that Congress now seeks to attach to administrative action are not merely the predrawn leading strings of statutes of which Woodrow Wilson wrote in Congressional Government.3

The relative importance of legislative intent was further enhanced by the recommendations of the 1949 Hoover Commission. In accordance with the commissions chief recommendation, the performance budget concept was implemented to make the statute more meaningful and to reduce the number of appropriations accounts (from 2,000 in 1940 to 375 in 1960).4 Hence, the appropriations committees no longer attempt to supervise the executive by specifying in the act the amount for everything from stationery to the salary of the guards at the Boston Ship Yard. Instead they employ statements in the committee reports and negotiate transfers informally during the year that exert a more flexible but, nevertheless, effective type of oversight.

Through the years the rules prohibiting legislation in an appropriations bill have been refined and many precedents are now established. The appropriations committees are not always content, however, to operate within the spirit of the rules, and therefore, use legislative intent to circumvent points of order that might be made against legislation in their bills. Furthermore, interviews with appropriations committee members reveal a decided preference for nonstatutory devices in many situations where the statute could be employed. As a result of these developments statutory provisos are restricted largely to housekeeping matters with a consequent increase in Congressional control techniques that do not involve the appropriations act.

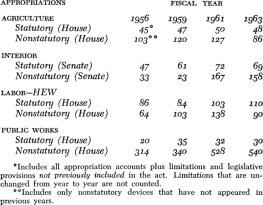

This study is based on Congressional consideration of six appropriations bills: LaborHealth, Education and Welfare; Public Works; Interior; Agriculture; State Department USIA; and Defense. The writer analyzed the basic Congressional documents for the period 1953-62: House and Senate Appropriations Committee reports, the hearings before the five subcommittees, and debate on appropriations bills in the Congressional Record. The reports were reviewed initially for committee expectations and instructions; second, the hearings were examined, particularly for discussion pertinent to the points identified in the reports; and third, the Congressional Record was reviewed for significant and relevant floor debate. A subcommittee demand or desire was followed, wherever possible, to a point of recognizable response by the executive branch.

This study relies on the printed record, and therefore, many instances of off-the-record control are not included. Some important generalizations, however, are derived from interviews that provided insights that could not be gathered from the record.

The interviews were semistructured and averaged forty minutes in length. Certain key questions, all open-ended, were asked of all respondents. The format was kept very flexible, however, in order to allow particular subjects to be explored with individuals best equipped to analyze them. In order to improve rapport with the respondent, notes were not taken but were transcribed immediately after the interview. Where unattributed quotations appear in the text, they are as nearly verbatim as the authors memory permits.

The writer interviewed three members from the House Appropriations Committee and three from the Senate Committee (who served on four different subcommittees). The chief clerks of three Senate subcommittees and three House subcommittees responded freely to all questions and made available the subcommittee mark-up notes. A draft of this manuscript was provided to the Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress and the writers conclusions were reviewed for their accuracy. Budget officers in all departments involved in the study were also interviewed.

1. Robert Wallace, Congressional Control of Spending (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1960), p. vii.

2. Arthur W. MacMahon, Congressional Oversight of Administration: The Power of the Purse, Political Science Quarterly, 58 (1943), 162.

3. Ibid., p. 162.

4. U. S. Congress, Senate Committee on Government Operations, Financial Management in the Federal Government, Senate Document No. 11, 87th Congress, 1st Session (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1961), p. 133.

Acknowledgments

The writer is indebted to the many government officials who furnished numerous insights into the importance and operation of appropriations control without passing laws. Although they must remain anonymous, no doubt they will recognize their contributions and statements throughout the study. The same must be said for the members of Congress and their staffs who gave unstintingly of their time.

Without the encouragement and counsel of Arthur Maass, chairman of the Department of Government at Harvard University, the writer would never have completed the study. His assistance was invaluable and his impress is on almost every section. Joseph Cooper of Harvard University played a crucial part in the conceptual framework. A Harvard seminar paper by John Berg provided the data on the Defense Department appropriations and a critique of several hypotheses advanced in this volume. Finally, W. Devier Pearson of the Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress was a most helpful critic. All contributors, however, must be absolved of any responsibility for the contents.