More Praise for Lost on Earth

"I hope many people will be touched as I am by the human tragedies Lost on Earth conveys with such emotion and talent."

Elie Wiesel

"It is a rare bit of luck these past 10 years that put a writer as gifted as Mark Fritz at most of our worlds historic venues ... a remarkable blend of history, analysis and humanity."

Detroit Free Press

"This is an unpretentious book, but it brings out lucidly the moral and political problems caused by one of mankinds greatest migratory upheavals. Lost on Earth is a series of vivid dispatches from this shadowland of outlanders, and at their best they are the premier reports about the contemporary refugee."

Boston Globe

"Lost on Earth is an enjoyable read, not least because of Fritzs eye for details."

Washington Monthly

"Recommended reading. Helps put the new refugees (from Kosovo) in a larger context by examining the world's new homeless."

USA Today

"Unfolds like a series of loosely interconnected short stories. Fritz writes with streetwise empathy for his dislocated subjects."

Publishers Weekly

"An arresting eyewitness account of the end of the Cold War."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"This is a book about travel, but the travelers have no home to leave behind, their destination is nowhere, and the reason for the trip is anything but pleasure. The fact that our nation of immigrants (and tourists) has its borders closed to them is terrible and humiliating."

P. J. O'Rourke, author of Eat the Rich and Holidays in Hell

"A vivid account and thoughtful examination of history s largest human migration,... All too often, these are the stories that go ignored by the American media; one must praise Fritz for bringing them to light."

Kirkus

"This is inspired reporting a trek through a world of dislocation and distress, a microscopic look at the human consequences of poor leadership and ignorance among our so-called family of nations. Mark Fritz focuses upon individual lost souls, then makes the connections to the reverberating waves of displacement that are slowly, but steadily, coming away,"

Arthur Kent, Emmy Award

winning war correspondent

"These are not just touching stories of poor refugees caught in a world gone mad. They are stories that starkly demonstrate just how interdependent the world has become."

St. Petersburg Times

Accessible and insightful... provides a context that's missing from daily headlines and nightly news reports."

Portland Oregonian

"To make real the usually hidden human dimension of the high politics we read about in the morning paper; to show people's stories to be interconnected and overlapping with others whose existence they can barely fathom; to provide food for empathy all are ambitious and important tasks that Fritz accomplishes with flair."

Current History

"Street stories from the main theaters of the migrations of the 1990s.... Sharp, contemporary journalism gives depth to the daily news images."

Booklist

"Fritz has laced this easily read and absorbing book with vignettes of refugees' journeys across borders and into lands they had no idea they ever would see. So many news stories have passed before our eyes in the last decade that we need a book like this."

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

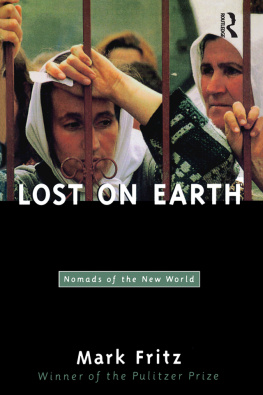

lost on earth

lost on earth

nomads of the new world

mark fritz

Published in the United States of America in 2000 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2000 by Mark Fritz

This edition published by arrangement with Little, Brown and Company, (Inc.). All rights reserved.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Fritz, Mark.

Lost on earth: nomads of the new world / by Mark Fritz.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-415-92609-2 (pb)

1. RefugeesHistory20th century. I. Title.

HV640.F75 2000

362.87'09'04dc21 99-088060

To Karyn

There is no greater sorrow on earth than

the loss of one's native land

EURIPIDES

WHO says the Berlin Wall has fallen? What do we mean the Berlin Wall has fallen? Did we see the Berlin Wall fall? Is there a big hole there?"

Frank Crepeau was holding a little slip of paper. It was a dispatch that had just come in from Berlin. It was filed with what was known as a flash priority, which was pretty much reserved for, say, the assassination of an American president or an invasion from outer space. It was a single sentence, unattributed, too remarkable to be real. It simply said that the Berlin Wall had fallen.

I was a copyeditor on the foreign desk of a wire service, The Associated Press in New York. Frank Crepeau was the assistant foreign editor. He'd worked in Moscow and Berlin and Prague, among other places, back in the days when nations were constructed to keep their citizens caged. I sat in the slot, the center of a horseshoe-shaped collection of desks, and he sat off to the side, waiting to pounce on the mistakes that the rewrites and the filers like me inevitably made during the chaos of deadline. So when something akin to science fiction popped up on the little printer at my right elbow, I handed the printer slip to him. And he looked at it with the incredulity of someone who had personally felt the chill winds of the Cold War.

He called the bureau in Berlin, East Germany's government had, indeed, lifted travel restrictions. The wall, technically, was open, Frank was satisfied. I pressed a key on my computer and put a bulletin on the wire. It was November 9, 1989. The Berlin Wall had fallen, and nobody could quite believe it.

Five months later, mostly by coincidence, I was sent to East Germany, and from there I took assignments to Moscow, the Persian Gulf, Somalia, Liberia, Rwanda, Bosnia and many other places. And it seemed like most of the stories I wrote in some way included a large number of people who had been forced to leave their homes, their jobs, their countries, their particular place in the world. Whether it was a Tutsi teenager on the road in Rwanda or a Togolese computer expert fleeing across the Sahara, every event seemed to have a sizable population of displaced people attached to it. But it wasn't until I came home five years later, after I'd left behind the little pieces of different places, that I realized how much all of these people were part of the same story.

In September 1995, during one of the many events held to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the United Nations, a group of diplomats, writers and humanitarians convened at Columbia University in New York to discuss a phenomenon that policy analysts refer to as forced migration. The purpose was to bring together people with a knowledge of the topic to discuss what to do about the multitude of refugees spawned by the porous borders, ethnically retooled homelands and overhauled ideologies that emerged when the Soviet Union quit the Cold War.