First published 2014 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2014 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2013032563

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Plight and fate of children during and following genocide / Samuel Totten, editor.

pages cm. (Genocide: a critical bibliographic review; volume 10)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-5355-2

1. Genocide. 2. ChildrenCrimes against. 3. Crimes against humanityHistory20th century. 4. Crimes against humanityHistory21st century. I. Totten, Samuel.

HV6322.7.P59 2014

362.88083dc23

2013032563

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-5355-2 (hbk)

Samuel Totten

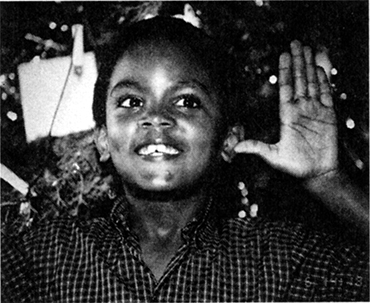

Generally, when I make my way through museums dealing with genocide I find myself feeling sad and angry but I forge on and make my way through the exhibits. This, I have done, time and again, beginning back in 1978 when I first visited Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1993, and the tiny museum on the Armenian genocide located in the basement of a church in Deir et Zor (Syria) in 2005. But then, in 2006, as I made my way through the museum at the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre in Rwanda, I entered the Childrens Wing, and within ten minutes my heart was shattered. I had only managed to view a tenth of the photographs and accompanying information in the room, but I simply could not go on. I literally wanted to scream and flay away at a world that would allow such horrific injustice and atrocities to be perpetrated.

I shall never forget the last photo and captions that ripped my heart apart. It was the sweetest picture of a young man, Patrick, seven years of age, Ive ever seen. His smile and bright sparkling eyes exuded joy. Then, I read the captions:

Name: Patrick Murinzi Minega

Favorite Sport: Swimming

Favorite Sweets: Chocolate

Favorite Person: His Mum

Personality: Gregarious

Cause of Death: Bludgeoned with Club

Over the years (during which I served as a Fulbright Scholar at the Centre for Conflict Management at the National University of Rwanda, and on subsequent research trips when Rafiki Ubaldo, a survivor of the 1994 genocide, and I conducted interviews for our book, We CannotForget: Interviews with Survivors of the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda), I returned to the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre several times in order to try to view all of the photographs and captions in the Childrens Wing. Each and every time Id only get so far before I was overwhelmed with sorrow, and, yet again, would depart without having viewed the entire exhibit. To this day Ive not viewed the entireexhibit.

The killing of infants, preschoolers, school-age children, and pradolescents should be beyond the pale. Unfortunately, and sadly, it is notat least not for those who are apt to committing crimes against humanity and genocide. And its not just killing that the latter engage in, but also the torture and butchery of babies and young children.

When perpetrators kill infants and children there is often a sadistic tone and tenor to their actions. They seem to enjoy exhibiting their perverted power over the victim population. They seem to enjoy crushing the spirits of those parents and siblings who are forced to watch their children and babies and young brothers and sisters, respectively, be brutalized in the most horrific ways possible. They seem to enjoy instilling terror into the victim population by ripping apart, crushing the skulls of, slicing the heads off of, and stabbing and shooting helpless and totally innocent members of the victim population.

Not even fetuses are safe from the ravages perpetrated by genocidaries. In just about every genocide one reads about, some perpetrators have ripped open the wombs of pregnant mothers, pulled out the fetuses, and destroyed them in front of the mothers eyes. It makes for ghastly reading; but that, obviously, is nothing next to what the horrified mother and her loved ones live through. In most instances, the mother, who is carved up as if she were some inanimate piece of meat, ends up dead.

There are, of course, numerous reasons why children are targeted during periods of genocide. Children are brutalized and killed by perpetrators in order to terrorize targeted groups and force them to flee from those areas coveted by the perpetrators or by those perpetrators who wish to cleanse an area of those others. By attacking the victim groups children, perpetrators believe that the targeted group is more likely to flee for safety and thus abandon their homes, villages, and/or farms.

Children are also targeted by genocidaires in order to cut off the lifeblood of the targeted group. Time and again during genocide, male infants and young boys have been targeted due to the perpetrators perception of them as potential foes and thus a security threat. This was certainly the case during the 1994 Rwandan genocide: The targeting of Tutsi children along with adults carried the idea ofself-defense to its logically absurd and genocidal end. To encourage assailants to kill children, some instigators stated that even the youngest could pose a threat; they often reminded others that Paul Kagame or Fred Rwigema, RPF commanders who led the guerilla force, had once been babies too (Human Rights Watch 2003, n.p.).

Female infants and young girls are targeted because they constitute the future bearers of children of the targeted group. In various societies (such as in Darfur, where Muslims perceive those girls and women who had been raped as damaged and not worthy of remaining with their families and fellow villagers), perpetrators targeted women knowing full well that, in many, if not most, cases, the babies conceived of the rapes would be considered Arab or Janjaweed babies, and thus ostracized by their own family members and fellow villagers, and, in the end, would not grow up to produce more foes of the perpetrators.

In those cases where children have been forced to fight alongside military, militia or rebel troops, they are perceived as fair game, since they pose a danger to the opposition. This is just one more reason as to why children should never be recruited to serve with any group of combatants.

This volume, the last I shall be editing for the Genocide: A Bibliographical Series (more on that below), is comprised of the following chapters by the following authors: (1) Australias Aboriginal Children: Stolen or Saved? by Colin Tatz; (2) Hell Is for Children: The Impact of Genocide on Young Armenians and the Consequences for the Target Group as a Whole by Henry C. Theriault; (3) Children: The Most Vulnerable Victims of the Armenian Genocide by Asya Darbinyan and Rubina Peroomian; (4) Children and the Holocaust by Jeffrey Blutinger; (5) The Fate of Mentally and Physically Disabled Children in Nazi Germany by Jeffrey Blutinger; (6) The Plight and Fate of Children vis--vis the Guatemalan Genocide by Samuel Totten; (7) The Plight of Children during and following the 1994 Rwandan Genocide by Amanda Grzyb; (8) The Darfur Genocide: The Plight and Fate of the Black African Children by Samuel Totten; (9) Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Children during Genocide by Elisa von Joeden-Forgey; and (10) Child Soldiers: Childrens Rights in the Time of War and Genocide by Hannibal Travis and Sara Demir.