First published 1994 in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

Copyright 1994 Routledge

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Politics of Immigration in Western

Europe.(Journal of West European

Politics, ISSN 0140-2382)

I. Baldwin-Edwards, Martin II. Schain,

Martin A. III. Series

325.4

ISBN 0-7146-4593-1 (hardback)

ISBN 0-7146-4137-5 (paperback)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The politics of immigration in Western Europe / edited by Martin

Baldwin-Edwards and Martin A. Schain.

p. cm.

First appeared in a special issue on The Politics of immigration in Western Europe of West European politics, vol. 17, no. 2 (April 1994)T.p. verso.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-7146-4593-1 (cloth)ISBN 0-7146-4137-5 (paper)

1. EuropeEmigration and immigrationGovernment policy. I. Baldwin-Edwards, Martin, 1956- II. Schain, Martin A., 1940

JV7590.P66 1994

325.24dc20 94-11485

CIP

This group of studies first appeared in a Special Issue on The Politics of Immigration in Western Europe1 of West European Politics, Vol. 17, No. 2 (April 1994), published by Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Routledge

Typeset by Florencetype Ltd, Kewstoke, Avon

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

MARTIN BALDWIN-EDWARDS and MARTIN A. SCHAIN

Immigration has emerged as a powerful political issue throughout all of Western Europe during the past decade. Hardly a day passes without some new revelation of an act of violence, an electoral change, the emergence of a new political party or association, or the debate of some policy initiative in a major European country. Indeed, in ways that were wholly unexpected just a few years ago, every aspect of political life has been touched by the issue of immigration. In every country in Western Europe, new movements have emerged, anti-immigrant political parties have gained electoral strength and have altered the balance of political forces. This new balance has influenced policy changes as governments have attempted to deal with challenges that threaten understandings and agreements which have existed for decades. The emergence of the issue of immigration has influenced the way in which European governments perceive and deal with such diverse problems as economic growth and change, social policy, security, and the political construction of Europe.

This Special Issue of West European Politics is devoted to an analysis of how immigration has emerged as a political issue, how the politics of immigration have been constructed, and what have been the consequences of this construction for politics in Western Europe. As we can see from the articles in this Special Issue, what has been termed the issue of immigration in fact involves far more than the flow of migrants legally entering Western Europe. It also involves asylum-seekers, residents without papers and the numerous foreigners and people of foreign origin who have been resident in Western Europe for many years and (in some countries) for several generations. The word immigration has often been applied to ethnic relations in what is becoming a de facto multi-cultural Europe. Mass publics perceive a vast increase in the presence of immigrants and the cross-border flow of migrants during the past five years. In fact, whatever the political validity of the perception, the reality is far more complex.

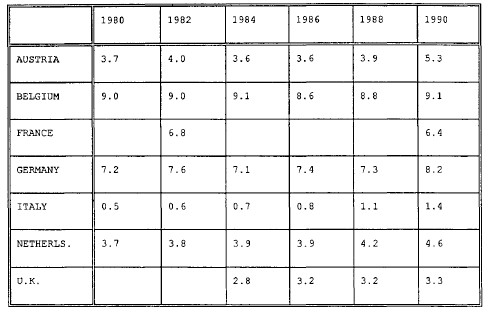

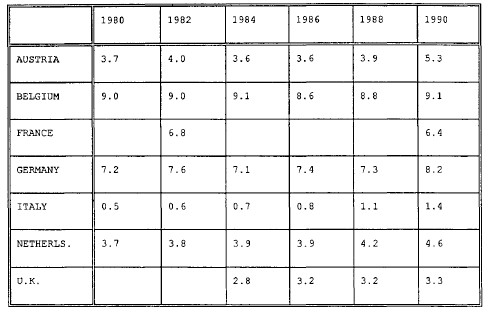

TABLE 1

PERCENTAGE OF FOREIGN POPULATION IN SELECTED OECD COUNTRIES

Source: SOPEMI, Trends in International Migration (Paris: OECD, 1992), p. 131.

TRENDS IN EUROPEAN IMMIGRATION

Legal immigration into Western Europe has been low if steady since the oil crisis of the 1970s, when most countries restricted immigration from non-European Community countries. During the decade of the 1980s, the percentage of foreign legal residents in Western Europe increased slightly (see Table 1), with the largest proportionate increases in Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Austria. In absolute terms, the foreign population increased most in Germany and actually declined in France. However, these figures must be read in the context of the low rate of naturalisation in Germany and the relatively high rate in France.

The legally present foreign population of Italy increased threefold during the 1980s, but remained under 800, 000. Perhaps more important, for the first time in modern history, Italy, along with other southern European countries, in the past decade has become a country of net immigration rather than of emigration. Despite these changes, the overall distribution of foreigners across Europe has remained largely unchanged, with the vast majority located in Germany and France, followed by the UK, Switzerland and Belgium.

Starting in the late 1980s, new flows of migrants have occurred.1 These include increases in both family reunion and guestworkers; flows

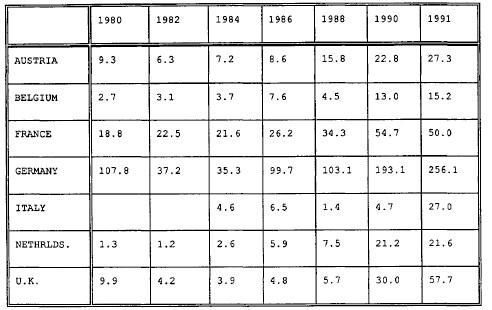

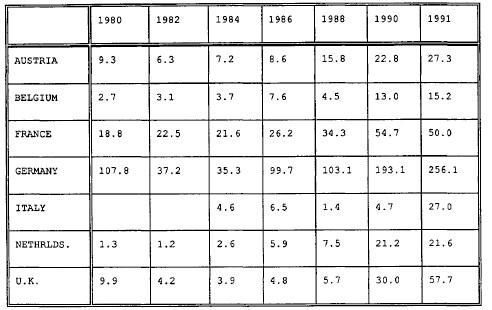

TABLE 2

ASYLUM SEEKERS INTO SELECTED OECD COUNTRIES (THOUSANDS)

Source: SOPEMI, Trends in International Migration (Paris: OECD, 1992), p. 132.

from Eastern Europe, mainly affecting Germany and Austria; largely illegal migration, mostly originating from Africa, into the southern European countries; and a marked increase in the number of asylumseekers.

Asylum-seekers

The number of asylum seekers increased dramatically in the late 1980s (see Table 2). The largest increase in absolute numbers was in newly unified Germany, although proportionately short-term influxes were greater in Belgium and the UK. Even before unification, more asylumseekers were entering Germany than the rest of the European Community. With the collapse of communist regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and with the expansion of the war in former Yugoslavia, the number of asylum-seekers grew rapidly in every country in Western Europe. This was particularly true in Germany, but only in Germany and Sweden did the number continue to increase through 1992. In France, the number of asylum-seekers declined after 1989, in Spain after 1990, and in the UK, Italy and Austria after 1991.