originated as a lecture to the Shavano Institute of Hillsdale College. Miss Kristen Sifert, Miss Eileen Balajadia, Mr. Matthew Davis, and Mr. Alan Cornettall Fellows of the Marguerite Eyer Wilbur Foundationmuch assisted me in preparation of the index to this volume.

Introduction

Mark C. Henne

I t is a commonplace that the defining characteristic of that characteristically modern literary form, the novel, is a concern for the revelation of the ordinary mans inner life. Hence the frequent use, beginning early in the novels history, of the device of diaries or letters (for example, in Richardson's Clarissa or Defoe's Robinson Crusoe ), culminating eventually in the stream-of-consciousness style of Joyce. This internal focus of attention stands in contrast to the classical concern of the epic with the external deeds of the extra ordinary man.

The modern psyche hungers to identify itself with a protagonist , and ashamedly eschews the implicit judgment against the prosaic rendered by the exemplary life of the hero. The modern self seeks to have its undemanding gestures of sentimentality confirmed as natural, even praiseworthy, and expects to see even bourgeois virtue revealed as hypocritical inauthenticity. In its critical mood, the modern self seeks to rummage beneath the public deeds of conventionally heroic figures to discover below the real, all-too-human, private man. Thereby, the modern self finds reassurance in its own mediocrity and moral failure. The tell-all biography is a special delectation for moderns.

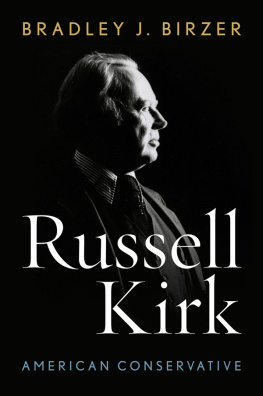

In The Sword of Imagination (1995), his autobiography and his last book, the late Russell Kirk (1918-1994) completed a lifetime of chastening the unruly passions and interests of modern men. In that book, a reader in search of confessional display and melancholy introspection is quickly confounded, as the dean of the conservative intellectual movement in America recounts a life of much incident, both public and private, a life, as he calls it, of literary conflict. And yet, as written, it remains a life in which the figure of Kirk stands at a distance, just beyond our grasp in his decorous equanimity. It is a life of formal reserve, propriety in the midst of domestic happiness; and it is a life that ends in quiet gratitude for the graces which are acknowledged to be such, unmerited. So little does Kirks memoir meet our modern expectation of the form that we are perplexed: why go to the trouble to write a memoir, only to hide ones authentic self behind a mask of eighteenth-century pious platitudes?

Most extraordinarily, a modern reader is confounded by Kirks decision to write his memoirs in the third person, thereby definitively frustrating the hunger for novelistic self-disclosure. Surelyone can hear the irritated objectionthis is simply impossible, this is affectation gone too far. To some critics, this last stylistic choice constituted a kind of proof that Kirk could be dismissed as no thinker, but only a poseur practicing an elaborate form of the Tory harrumph. The style of Kirk's prosethe meandering sentences, the unattributed references to Bunyan, the promiscuous use of aphorisms and epigrams, the disengagement from details, the sheer, untroubled confidence of the historical and theoretical assertionsis certainly a provocation to the contemporary academic mind. His ornate prose is often a stumbling block even for those who come to Kirk's writings with an open mind. But rather than dismissing the message because of the medium, perhaps it would be wiser to consider Kirk's provoking style in a different lightas a prompting to inquiry.

For there remains a larger Kirk problem to be resolved, a decade after his death; it is a problem about categorization. What exactly was the nature of Kirk's project? What kind of thinker and writer was he? The Conservative Mind (1953), Kirks major achievement and the book that gave the modern American conservative movement its very name, is at one level a work of historical scholarship. But as it purports to be a history of normative political theories, a normative dimension cannot be ignored. And when we examine the rest of Kirks large corpus, we find familiar essays, reminiscences, literary criticism, local histories and grand histories, character sketcheseven ghost stories and textbooksand in this book, a collection of lectures, all but one first delivered at the Heritage Foundation, one of Washington's premier public policy think tanks. With little variation, the style is always the same. What was Kirk attempting to effect with his idiosyncratic writing? To what was he responding? How might his writings constitute a response?

Even if we restrict ourselves to Kirk's scholarship, ought we to consider The Conservative Mind as a work of political theory? If so, it is political theory of an eccentric sort. The book begins with an encapsulation of conservative thought in six canons. But these appear to be yoked by no logical necessity, and none of them has more than an indirect relationship to political forms and institutions. The canons have none of the reductive clarity of the terms in which one can consider the development of, say, liberalism: parliamentary representation, the protection of rights, the priority of property, etc. As Kirk moves through his account, it is even evident that various of his conservative minds violate one or another of the canons.

Ought we instead to consider The Conservative Mind as a work of intellectual history? Again, it would be a very odd contribution to that literature. Kirk troubles himself not at all with demonstrating chains of intellectual influence, content with adducing something like a family resemblance among the thinkers he discusses. The negative work of careful discrimination, so necessary for intellectual history, appears only sporadically. The particularities of historical circumstances tend to fall away as Kirk works up a conservative archetype in that extended essay in definition.

Rather than as either a political theorist or as an intellectual historian, Kirk considered himself to be a man of letters, going so far as to have this inscribed on his tombstone in Mecosta, Michigan. This is a term which has nearly disappeared from current usage. While there is now a cottage industry of journalists decrying the depletion of our stock of public intellectuals, the man of letters is so distant from contemporary experience that we can scarcely conjure any image of the type. The man of letters is a writer: but what kind of writer? In its imprecision and deliberate archaism, the term seems merely to keep Kirk at a distance. But it also invites us further into the question of how Kirk understood his workand how we can understand it as well. The place to begin is The Conservative Mindy which was first published half a century ago.

T he intellectual milieu in which Kirks thick book appeared has been frequently recounted, notably in George Nash's definitive study, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. In 1950, the Columbia literary critic Lionel Trilling had written that in the United States of his day, liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition. By 1955, the Harvard political theorist Louis Hartz would trump Trilling, contending that, in fact, there never had been nor could be anything but a Lockean liberal tradition in America, because America had been bourgeois from the beginning. Hartz's maxim was, no feudalism, no socialism , but a necessary corollaryunstated, because so patently obvious was: no true conservatism either. Daniel Bells 1962 book, The End of Ideology consisting of chapters written during the 1950scaptured well the spirit of this period. It was the first end of history, with Americas elites unable to imagine anything but the never-ending advance of various syntheses of liberal and socialist progressivisms.