In June 2010 Americas war in Afghanistan surpassed the Vietnam War as the longest war in Americas history. American, British and coalition forces have been fighting in Afghanistan since October 2001, a month following the attacks on the Twin Towers in New York. By the end of the year the war seemed won. But a decade on, the ongoing conflict seems far from over.

Map of Afghanistan

Todays conflict has historical parallels in the nineteenth century Great Britain twice invaded Afghanistan, in 1839 and 1878. Both times it had seemingly defeated the Afghan forces only to find that the Afghan soldier, not knowing the meaning of defeat, fought back, inflicting humiliating retreats on the mighty British Empire.

A century later, the Soviet Union, technologically and militarily superior, also discovered to its cost that the Afghan was a tenacious foe, impossible to defeat. After a decade of conflict the Soviet Union withdrew, its military reputation in tatters.

Afghanistan has been in a state of constant conflict for almost four decades. When not fighting external enemies, its people have fought against each other. The civil war of 1989 to 1996, during which the Taliban emerged, was ferocious in its intensity.

The coalition forces of today are embroiled in a seemingly unending war. But why are we still fighting in Afghanistan? What are the lessons of history? Who are the Taliban; who are the Mujahideen, and why was Osama bin Laden so significant?

These, in an hour, are the Afghan Wars.

In the summer of 1837 the young Victoria ascended the British throne. The Empire was still expanding and at its core gleamed India, the jewel in the crown, the heart of the realm. But to the north-west lay Russia, a rival power with expansionist ambitions. The fear of Russia and Russian influence was a constant factor in Britains foreign affairs during the mid-nineteenth century, referred to euphemistically as the Great Game. When, in 1836, Russia extended her influence into Persia (modern-day Iran), Britain feared for India. Between Persia and Indias north-west frontier lay Afghanistan and it was to this rugged, inhospitable country that Britain turned its attention.

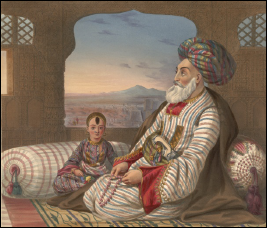

The Amir of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad Khan (pictured below), had received delegations from both British and Russian dignities. Although the British managed to persuade Dost to decline Russias offer of aid, they considered him unreliable and decided that in order to save Afghanistan from Russian interference they needed to replace him with someone more compliant to their own needs. The man they had in mind was Shah Shuja, a former king of Afghanistan, who had been deposed in 1809 and remained a figure of loathing throughout the country. But Shuja, now residing at Britains expense in India, had the advantage, in Britains eyes, of being pro-British.

Dost Mohammad Khan, Amir of Afghanistan, 18261839 and 18431863

Lord Auckland, Governor-General of India, proposed that the British army escort Shuja back into Afghanistan, oust Dost Mohammad, and place Shuja on the throne where, according to the British, he rightfully belonged. The Afghan nation saw Shuja in a different light but this inconvenient fact was ignored by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who agreed to Aucklands proposal, known as the Simla Manifesto. Thus the stage was set for the First Anglo-Afghan War and one of Britains greatest military humiliations.

Towards the end of 1838, Britains Army of the Indus was assembled in Lahore, consisting of almost 10,000 British soldiers and 6,000 soldiers loyal to Shah Shuja (pictured below). The typical British officer of Victorias earlier years did not travel light and insisted on bringing with him all the luxuries of the officers mess. Thus the troops were accompanied by 38,000 camp followers cooks, butlers, valets and servants, together with 30,000 camels to carry all the essentials of a military expedition wine, brandy, cigars, perfume, soap, bed linen and luxurious food. Add to this enough cattle, sheep and goats to feed the expedition for three months, together with the herdsmen to look after the beasts and the butchers to slaughter them.

Shah Shuja, Amir of Afghanistan, 18031809 and 18391842

By July 1839 this huge, cumbersome train of soldiers and personnel had reached the fortress city of Ghazni in eastern Afghanistan, south-west of Kabul. Along the way the soldiers had seen off numerous gangs of marauding Afghan tribesmen but Ghazni presented the first obstacle on the way to Kabul, capital of Afghanistan. The British stormed the walled city, massacred 500 of its inhabitants and secured fresh provisions. The route to Kabul now lay ahead, within easy reach.

As the convoy approached Kabul, Dost Mohammad fled. The British entered the city unopposed, placed Shah Shuja on the throne and congratulated themselves on a job well done. Having sent most of the army back to India, the remainder settled down to a life of indolence and luxury. They sent for their wives and families and enjoyed cricket, horse racing, music and dancing, while the local Afghans looked on with growing disdain.

Sir William Hay Macnaghten (pictured below) was appointed Minister of Kabul with Sir Alexander Burnes his second-in-command. After a year Macnaghten decided that their situation was secure enough to move out of the capital and set up a settlement, or cantonment, a mile north. It was a decision of staggering foolishness. Surrounded by aggrieved locals, the cantonment was separated from the city by an expanse of orchards, gardens and canals which, in an emergency, would hamper the movement of horses and men; the perimeter was too long to defend and the stores of provisions were situated a quarter of a mile outside the cantonment.

Sir William Hay Macnaghten (17931841)

A second British garrison had been stationed at Jalalabad, ninety miles east. In order to secure the route between the cities the British paid the local tribesmen who controlled the dangerous mountain passes for the guarantee of a safe passage. But in an effort to save money, Macnaghten cut the payment by half. Furious, the tribesmen plundered the first caravan to pass through. Macnaghtens economy drive had, in effect, cut the Kabul garrison off from Jalalabad.