Europe in the early twentieth century was a continent of superpowers and would-be superpowers. Motivated by ambitions of self-aggrandizement and self-preservation, they eyed each other with suspicion, envy and often fear bordering on the paranoia.

Germany

Germany was the cause of much of this fear. A unified country only since 1871, Germany, under the careful management of its chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, had rapidly built itself up into a modern, militaristic, industrial powerhouse. It looked to the colonial assets of its neighbours, especially the vast, sprawling empire of Great Britain, and set on a course of obtaining its own empire, colonies, its own place in the sun. And for that, it needed a navy that could rival Britains, whose naval supremacy had ruled the waves since the days of Nelson a century before. The German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, had, as a boy, admired the proud British ships, and wished as an adult to possess a navy as fine as the English.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, 1905

Germany realized that Russia was becoming stronger, building its military and industrial capacity and extending its network of railways a vital factor in moving huge armies across large distances. If there was to be war, the longer it was delayed, the greater the strength of Russia: Every year we wait, lessens our chances, said the German chief-of-staff, Helmuth von Moltke (the Younger).

Great Britain

Great Britain, on her part, wanted nothing more than to protect her empire which, as every British schoolchild was taught, covered a quarter of the globes landmass and the associated opportunities for commerce the empire provided. For much of the latter half of the nineteenth century, Britain had remained aloof from international affairs, concentrating only on matters of self-interest and its empire consisting of 400 million people a situation it called its splendid isolation. The emergence of Germany as a perceived new threat, to both Britains colonial holdings and to the nation itself, changed that.

Knowing the importance of its navy not simply for the empire but for home security as well, and increasingly fearful of Germanys expansive desires, Britain was determined to maintain its dominance. In 1906, Britain launched the first of a much-feared new class of battleship, HMS Dreadnought, which was far superior to anything that had previously sailed. As well as this, Britain implemented legislation to ensure continual commitment to naval expansion, despite the enormous cost involved, thus engaging in an arms race with Germany. (By 1914, Britains fleet of battleships numbered forty-nine, outstripping Germanys fleet of twenty-nine.)

Britains fears of German intent were also fuelled by the widening of the Kiel Canal. The sixty-mile canal, originally opened in 1895, cut through the base of the Jutland peninsula, linking the Baltic Sea on the east and the North Sea on the west. Its widening, and deepening, completed in early 1914, allowed the passage of German warships, giving them easy access into the North Sea, a prospect viewed with dismay in Britain.

Britains sense of military superiority had been temporarily dented following the Second Boer War of 1899 to 1902. Technically, Britain had walked away the victors, but that it took three years and some unethical, ungentlemanly tactics to defeat a perceived ragamuffin collection of white South Africans of Dutch origin had shaken the British military and political establishment to the core. But calls in Britain to introduce military conscription in order to be better prepared in the event of a future war, and not suffer another humiliation as experienced in South Africa, were continually dismissed by Herbert Asquith, Liberal prime minister from 1908.

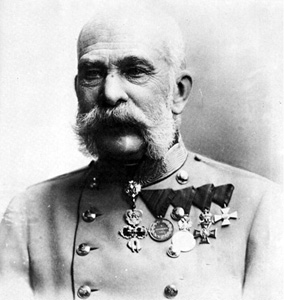

Austro-Hungarian emperor, Franz Joseph, c. 1915

France

France was a nation that was still licking its wounds since the humiliating defeat to the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War of 18701. The Prussians, Germanys predecessors, had taken as a spoil of war the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine and extracted massive reparations to the tune of 5 billion francs, and for the French this was the cause of much indignation. It was a wrong that needed to be righted. But the French knew full well they were no match for the expanding might of Germany. And this was the cause of much anxiety.

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia

Russia also harboured dreams of expansion towards the Pacific in the east. But, after a two-year war, the Russians, like the British in South Africa, were humbled by a supposedly inferior foe, the Japanese. The Russian tsar, Nicholas II, had hoped the Russo-Japanese War of 19045 would distract his people and quell the simmering unrest infecting his empire and restore national prestige. Instead, defeat merely intensified the sense of dissatisfaction with the tsar and his autocratic rule, leading to unrest and public demonstrations. Nicholas responded to what became known as the Russian Revolution of 1905 with the promise of democracy and reform, promises he reneged on almost as soon as they had been implemented.