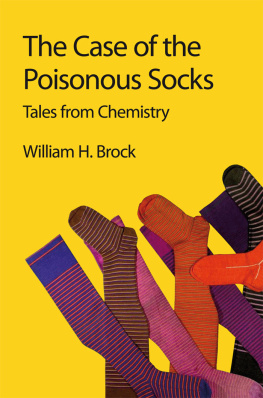

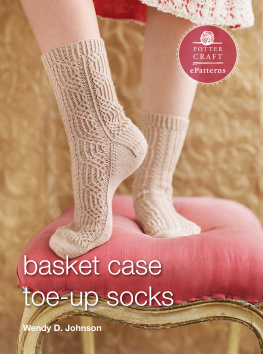

Front cover image: Stockings coloured by new bright synthetic dyestuffs prepared from aniline. Each stocking has NC & S 1862 woven into the welt to show that it was made by the Leicester company of Nathaniel Corah & Sons for the International Exhibition held in London in 1862. At the same exhibition, William Crookes exhibited a sample of thallium, a new metal he had detected spectroscopically the previous year. (Leicester Museums)

ISBN: 978-1-84973-324-3

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

William H. Brock, 2011

Reprinted 2015

All rights reserved

Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of research for non-commercial purposes or for private study, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003, this publication may not be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of The Royal Society of Chemistry or the copyright owner, or in the case of reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency in the UK, or in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the appropriate Reproduction Rights Organization outside the UK. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to The Royal Society of Chemistry at the address printed on this page.

The RSC is not responsible for individual opinions expressed in this work.

Published by The Royal Society of Chemistry,

Thomas Graham House, Science Park, Milton Road,

Cambridge CB4 0WF, UK

Registered Charity Number 207890

For further information see our web site at www.rsc.org

Preface

One of the many stories told of Ernest Rutherford is his reply when he was congratulated upon a particularly creative discovery. You are a lucky man, Rutherford, you are always on the crest of a wave.! To which Rutherford observed: Well, I made the wave, didnt I? Then, after a short pause, he added, At least to some extent. The moral of this anecdote is that even the most creative of scientific thoughts or experiments are dependent upon the work of earlier investigators.

Of the writings of histories of chemistry there can be no end. In the 1980s and 1990s there was a flourish of such historical activity. Three histories of chemistry were published in English in 1991, three more (one of them in French) in 1992. One of these contributions was David Knights Ideas in Chemistry: A History of the Science (1992), which was not a history of chemistry in the conventional sense. It did not offer the reader a chronological or thematically detailed account of the development of chemistry since antiquity. Rather, it was an account of scientific idea and practices in the form of self-contained essays in which chemistry was used as the exemplar. For Knight, chemistry was a finished science. He did not mean by this that, in future, chemistry would spring no surprises (Buckminster fullerenes were, after all, the chemical sensation of the 1990s), but that with its reduction to the behaviour of sub-atomic particles and electron clouds, chemistry was no longer at the leading edge of scientific ideas but instead, par excellence, the central service science which underwrites our understanding of biology, medicine, solid state physics and the whole gamut of everyday technology. In this sense, it is an ideal dead science whose biography can be written, rather like that of a writer or artist whose career and work is complete but whose paradigmatic inspiration lives on and whose writings or canvases invoke a plethora of normal science puzzle-making and puzzle-solving.

The essay form has had a long tradition in the history of chemistry, beginning in the seventeenth century with Robert Boyles effusive reports on colours and many other subjects and proceeding, notably, through Richard Watsons Chemical Essays (1781) and Justus Liebigs Familiar Letters on Chemistry (1843) to the twentieth century, with the thought-provoking writings of Primo Levi and Erwin Chargaff.

Liebigs essays, which began as informative newspaper articles, grew in book publication into vehicles for arguing a point of view and for paying off old scores, but above all for demonstrating that chemistry was essential knowledge for understanding plant and human physiology and for solving problems of health and nutrition, as well as saving the world from Malthusian agricultural damnation and misery. Inspired by Liebigs example, from the end of the nineteenth century until the 1940s it was common for historically-minded chemists to publish collections of their occasional contributions to non-scientific periodicals, informal talks and speeches to clubs and societies, and obituaries of chemical colleagues with whom they had trained or collaborated. Many of these, like August Wilhelm Hofmanns Zur Erinnerungen an vorangegangene Freunde (1888), W. A. Shenstones The New Physics and Chemistry (1906), James Campbell Browns Essays and Addresses (1914), Frederick Soddys Science and Life (1920) and John Reads Through Alchemy to Chemistry. A Procession of Ideas and Personalities (1957) are still consulted by historians today.

The present book contains essays and reviews written over the last forty years after I left chemistry to practise as an historian of chemistry. The essays have been revised and updated and shorn of academic documentation to make their reading simpler and, I hope, more enjoyable for historically-minded chemists, as well as for general readers. The collection is divided into six sections, each with its own introduction. The first, which is arranged in a rough chronological order, contains chemical tales which explore some of the ways that chemistry has seen its future. The second looks at the social history of chemistry and the way it has been organized. A third section offers vignettes of some major figures in chemistry. The fourth shows that women chemists have had a significant role in the development of chemistry. A fifth group of essays deals light-heartedly with a number of chemistry books and journals that have intrigued me. The book ends by examining a number of chemists who, for various reasons, have made their names in different fields. Some suggestions for further reading are given for readers who would like to follow up any of my chemical tales.

Books like this, wrote Knight in his Ideas in Chemistry, resemble paintings done with a broad brush, and are successful if they stimulate readers to take an interest in the history of chemistry. Like Liebig, my aim in this book is to beget a better public understanding of science, qua chemistry, via an historical viewpoint. It is in tune with the feelings of most responsible historians of science that our subject has a role to play in public and scientific education. Because science is the most important civilizing influence since Christendom, our historical interpretations deserve a wider audience than that of the seemingly diminishing number of professional historians of science.