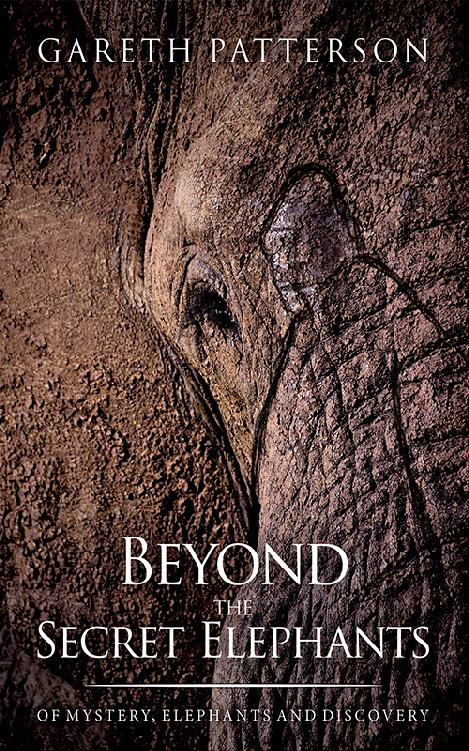

Fransje and I settled into a pine house on a hillside encircled by plantations, fynbos and patches of indigenous forest. To the south was a sweeping view down to the Knysna lagoon and to where the blue sky meets the blue waters of the Indian Ocean. To the north lay the wide expanse of the central portion of the dense and deep green Knysna forest, beyond which were the foothills of the Outeniqua Mountains.

The house was ideally situated, only seven kilometres from the town of Knysna, and literally almost a stones throw from the edge of the central forest.

In the years to come I was to discover that the Knysna elephants ranged as close as two kilometres to where we lived, and that also we were living in the midst of the range of the mysterious beings.

In undertaking full-time research into the Knysna elephants, my baseline objectives were to try to establish the number of the elephants and the extent of their range, to learn which habitats they were utilising within that range, and to establish what their diet was.

My objective was never to physically track down the elephants on foot, see them and photograph them. This would have been stressful for the elephants. My research was non-invasive and based on respect for the animals.

Elephants in the southern Cape had been tracked and hunted down since the white man first colonised southern Africa more than 350 years ago. It has been estimated that prior to colonisation some 100 000 elephants may have existed in what is present day South Africa with approximately 10 000 of these elephants existing in the southern Cape. By 1910 virtually the entire elephant population of the country had been wiped out by professional ivory hunters, sportsmen and settler farmers. By this time only some 200 elephants remained in four separate populations the southern-most being the Knysna elephants.

In 1970 elephant researcher Nick Carter, who spent a year studying these elephants, estimated that only eleven or twelve existed. The persecution did not stop. Just after Carters study, a forester working with the forestry department, in what was meant to be a clandestine killing, destroyed the most famous of the Knysna elephants the main breeding bull Carter had named Adam (and also known as Aftand by the local people). The killing was uncovered, and those involved were charged, but many believed that Adam was not the only Knysna elephant to have been killed by the forestry authorities.

The Knysna elephants that I was about to study and learn about were relict survivors descendants of victims of mass genocide.

My routine each day would be to drive out into the elephants range and to walk for half a day learning about the Knysna elephants from the signs they left behind, such as their droppings, footprints and feeding signs the strewn branches and leaves. It was calculated that in the first few years of the study I covered some 22 000 kilometres on foot, the equivalent of walking halfway around the world.

Early on, contrary to what had been previously claimed by the forestry authorities, I learnt that the Knysna elephants were not restricted to the dark confines of the forests, but roamed widely on the fynbos foothills of the mountains. At the commencement of my study it was thought that the last remaining elephant ranged in perhaps 100 square kilometres of the central forest. Today we know that the population ranged in over 700 square kilometres of mountain fynbos, the plantations, the forest and the forest edge.

Within several weeks of starting my study it was clear to me that definitely more than one elephant existed. I was finding footprints and droppings of various sizes, indicating different individuals. By measuring the diameter of the hind footprints of elephants, their ages can be determined, and the same applies to measuring the circumference of dung balls. Early evidence was showing that the Knysna elephant population was made up of comparatively young adults. Those were uplifting times.

***

During the early months of the elephant study, I do not think I ever thought about the mysterious beings the German tourists claimed to have seen two years earlier. This was to change one morning when I was having a meeting with a forestry department botanical scientist at his office in Knysna. The scientist, Johan, and I had arranged to meet to identify some of the plant types the Knysna elephants were eating. Somehow during the meeting, the subject changed to the bushman paintings in the vicinity of the Knysna forest.

Then, quite unexpectedly, Johan asked me, Gareth, while you are out walking in the forests and the mountain fynbos, have you ever come across a type of furry upright walking ape?

Juans story came flooding back into my mind.

I replied that I had not and enquired why he had asked.

I ask, said Johan, because in the past couple of years we have had two separate reports from our forest workers seeing such a creature. They were absolutely shocked at the sight. The men are adamant that it walks upright and is covered in hair. I would be very interested to know what it is.

I thought this conversation with Johan was curious. The story of the mysterious beings had arisen again, totally unprompted by me, and the subject had been brought up by a scientist who seemed to be open minded about its existence.

Thoughts about the mysterious being slipped out of my mind again in the days and weeks that followed as I began to find dramatic evidence of the Knysna elephants.

Early one grey overcast morning I was walking on a track through a pine plantation that borders an edge of the central forest when suddenly I heard a cracking sound ahead of me. I had a strong feeling that the source of the sound was elephants.

I continued onwards and at a point where the track split, one branch leading north, the other south, I found the fresh tracks of two young elephants.

The larger of the tracks was unlike any elephant footprint I had ever seen before. Instead of being etched with the usual mosaic of creases and lines, the back right footprint had an almost patchwork appearance. Immediately a name for this elephant came to mind Strangefoot.

Measuring Strangefoots hind track and that of the second and smaller elephant, indicated that they were approximately fourteen and eight years old respectively. I named the smaller one The Youngster. The fact that these were young elephants clearly illustrated that breeding had taken place in comparatively recent years, and that the Knysna elephants were a breeding population.

Continuing along the track, I soon came across a very fresh pile of droppings. The elephants had indeed been the source of the cracking sound I had heard earlier, and now they were close by. Walking onwards, I came across young trees that had been pulled to the ground and were strewn across the track. The weather was turning rapidly and the clouds had become menacingly dark.

Suddenly I heard the elephants to my right, followed by a loud crash of branches. As raindrops began to pelt down, I decided to move away. It would have been foolhardy to remain where I was, considering the conditions and my proximity to the elephants.

As I returned the way I had come, the rain began to pelt down hard and incessantly. Soon all I could hear was the rain. I had made the right decision.

Walking back through the forest to my vehicle in the pouring rain, I felt wonderfully elated by my discovery of the two young Knysna elephants.