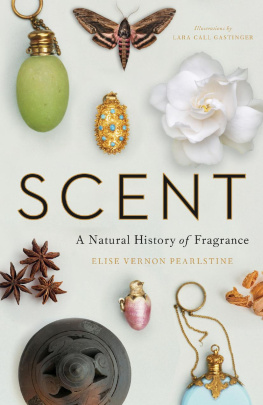

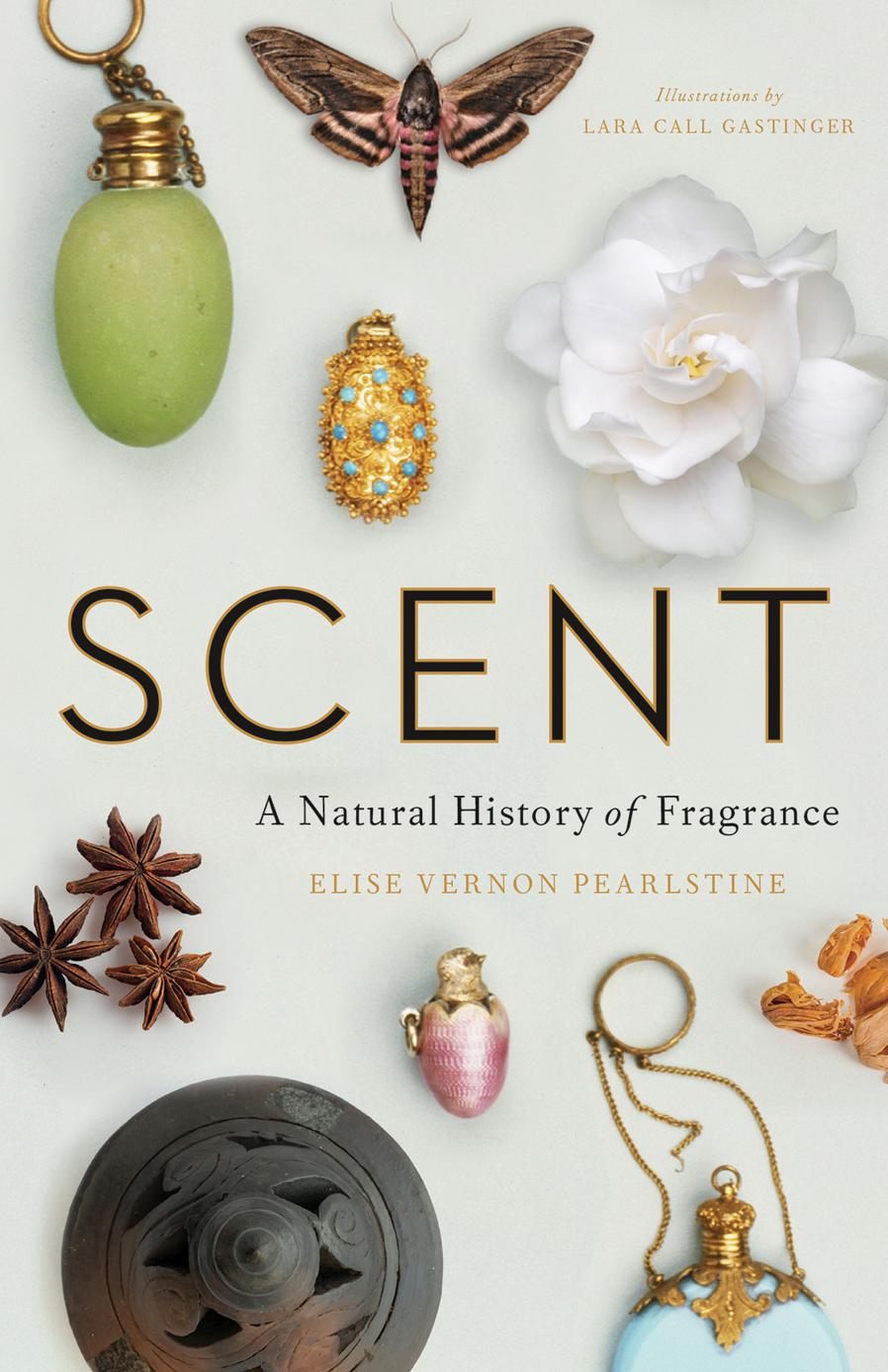

Scent

This page intentionally left blank

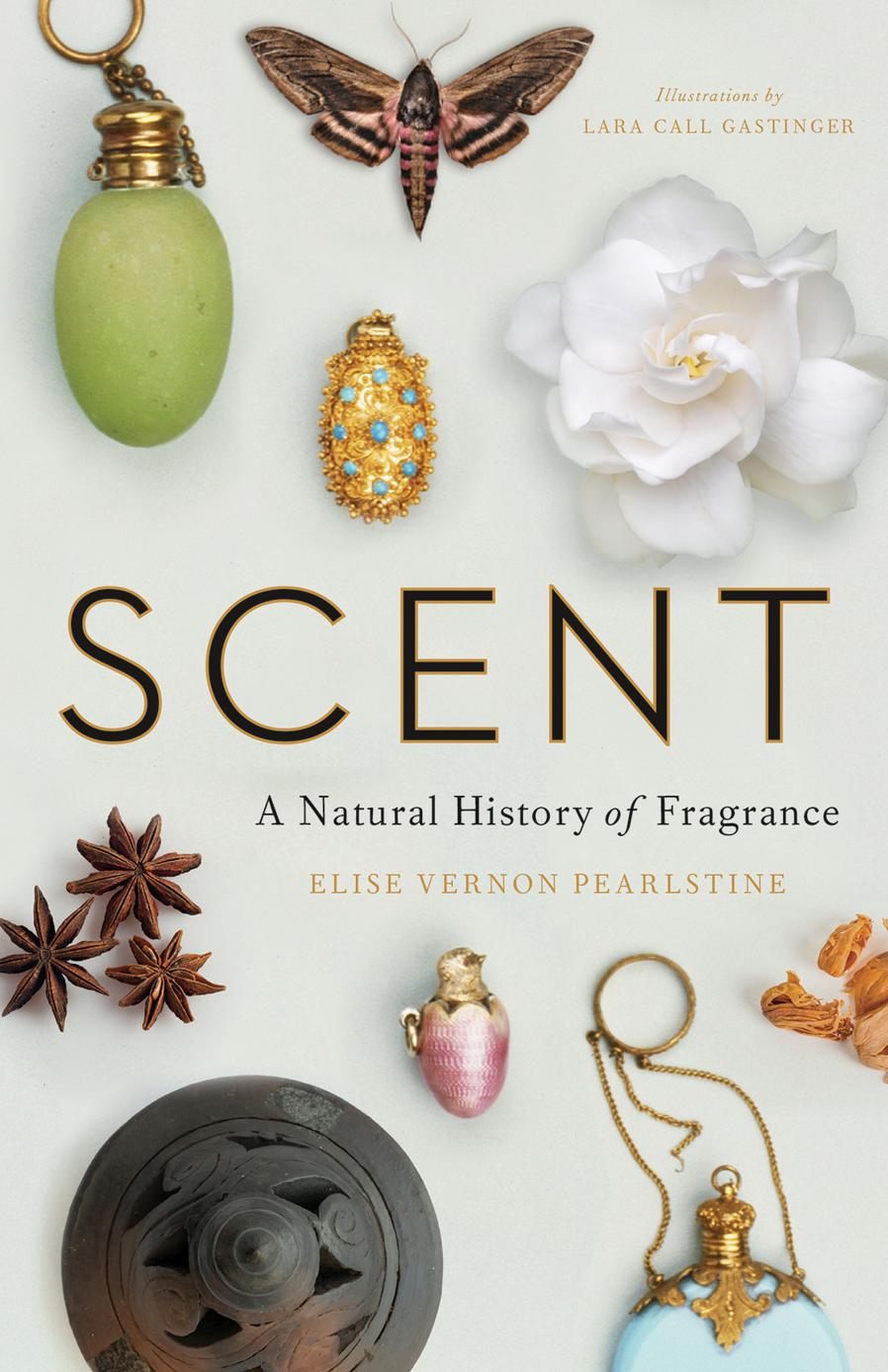

S C E N T

A N A T U R A L H I S T O R Y

O F F R A G R A N C E

E L I S E V E R N O N

P E A R L S T I N E

I L L U S T R A T I O N S B Y

L A R A C A L L G A S T I N G E R

New Haven and London

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2022 by Elise Vernon Pearlstine.

Illustrations copyright 2020 by Lara Call Gastinger.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including

illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107

and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail

(U.K. office).

Set in Adobe Garamond type by IDS Infotech Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021948038

ISBN 978-0-300-24696-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Leonard, who listens to my stories, and to Alison, Mike, Ben, Tim, Andrew, and Avery

To Michelyn, who helped me find my voice

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

vii

C O N T E N T S

viii

Before history recorded such things, people would strew aromatic

herbs on a floor, use pine boughs to freshen a home, or blend flower petals in oil to rub on chapped hands as a way to add fragrance to their lives. Today there may be an aromatic candle or two, fragrant lotion, perfumes and potions, and even scented toilet paper. Gardeners value aromatic plants, waiting impatiently for their fragrant lilacs to bloom, and nearly everyone will bury their nose in a bouquet of flowers to get a sniff of the floral and green. Visit any bookstore and you will find books about gardening, even gardening for specific interests or regions.

There are also an increasing number of books on the behavior of

plantshow they respond to each other, attract pollinators, and interact with their environment. You can find blogs and books about perfumes and fragrance. What ties these themes together are aromatic

chemicals called plant secondary compounds that play a role in the protection, pollination, behavior, environmental response, and health of plants. Blending story and science, this book will take you through history and around the world to investigate the smelly molecules that plants produce and how they have affected our world. Although we

love our fragrant plants and their products, humans have played a minor role in the evolution of aromatic compounds, also called volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. It is the moth, the bee, the beetle, the bat, the fungus, and the microbe that have driven evolution in plants to give us ingredients for perfume, incense, potions, and medicine. As ix

P R E FA C E

a perfumer and naturalist, I have found the inspiration to research and write this book through my appreciation for scented plants and their tiny friends and enemies.

The natural history of fragrance involves tales of incense, spice, gardens, and perfume. From frankincense to jasmine, plants show us their relationship with humans and the world around them through

the functions that aromatic chemicals play in flower, leaf, and seed.

Environmental characteristics, often called terroir, influence the volatiles that a plant produces, and this book places familiar scented plants and their products in the soil of their homeland. History has turned on aromatic products such as incense and spice, and industries have been built on fragrant ingredients. Ancient and modern global patterns of trade and manufacturing provide context and contrast with the intimate experience of smelling a flower from your garden, cooking with spices, or perfuming your personal spaces.

Fragrance perception is a difficult thing to quantify, very per

sonal, and one of the senses for which we have few descriptors. For the plants in this book, I have included descriptions of scent that are derived from my knowledge of plant essential oils and extracts gained from years of comparison and contrast to build my scent

memory, as well as from descriptions that can be found in the literature. Not everyone smells things the same way, and my goal is to

provide some groundwork on how to experience and describe a scent

and to show you a way to smell, describe, and enjoy the fragrant world that surrounds us all. Writing about volatile organic chemicals involves naming and describing the molecules that influence a plants interactions with the world. Depending on your interest you may

want to treat the constituents in the book as tools the plant uses, or you may be interested enough to read more about the chemistry

behind fragrances. Using plants as medicine is a practice as old as time and the subject of much current research, but aside from a few in-x

P R E FA C E

stances, I have chosen to limit discussion of medical uses to keep the focus on fragrance.

Although we did not cause the rose to breathe out scent or the

frankincense tree to shed fragrant tears, our stories are intertwined and mediated through the plant secondary compounds that we call

fragrance. Released from damaged leaves, delicate petals, resinous trunks, green stems, pollen, nectar, seeds, and leaves, plant volatiles are made in response to pollinators, predators, and pathogens. Apart from a small percentage of plants bred for scent, the smells we appreciate, and use, are created neither by us nor for us.

To tell the story, my tale will follow the history of our use of aromatics from ancient times to modern day with themes of spirituality and mysticism; power, revolutions, and control; gardens; and fragrance as perfume, industry, and fashion. For people, the story begins with mysticism and with scented smoke rising to the heavens, taking its sweet smell as a message to the gods. Resins such as frankincense, myrrh, cannabis, and copal and woods such as sandalwood and agarwood have a long history of use for incense and trade. Molecules from the wood of trees are complex; they are often large, they are healing, and they are greatly valued in perfumes, traditional medicine, and religion. Resins smell of pine, lemon, freshness, and terpenes, smaller molecules that can be experienced in woodland walks or the rising

smoke of incense.

Small enough to fit into little bottles on a kitchen shelf and yet with a huge fragrance, spices have had a worldwide influence on trade and exploration. There was a time when the mysterious sources of such spices as pepper, clove, nutmeg, ginger, and cardamom were the subject of secrecy and legends. Explorers followed those elusive hints to find the sources and help establish empires and create vast wealth.

Spices are the flowers, fruit, bark, roots, and seeds of herbs, vines, and trees, each producing characteristic fragrances and tastes from a suite of xi

P R E FA C E

molecules that are often antimicrobial and protective in nature. Their habitats are the warm woodlands and remote islands of the world.

Next page