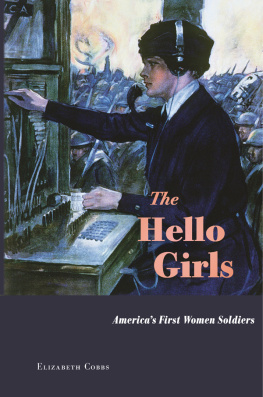

The Hello Girls

AMERICAS FIRST WOMEN SOLDIERS

Elizabeth Cobbs

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2017

Copyright 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Frontispiece: Merle Egan was twenty-nine, unmarried, and inspired to serve. After the war, she fought the U.S. Army another six decades. Merle Egan, 1917, National Personnel Records Center (NPRC), St. Louis, Missouri.

Jacket illustration: Back Our Girls Over There, Poster Collection, US 477, Hoover Institution Archives.

978-0-674-97147-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

978-0-674-97854-6 (EPUB)

978-0-674-97855-3 (MOBI)

978-0-674-97859-1 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Cobbs Hoffman, Elizabeth, author.

Title: The Hello Girls : Americas first women soldiers / Elizabeth Cobbs.

Other titles: Americas first women soldiers

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016038111

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19141918Communications. | Telephone operatorsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | World War, 19141918Participation, Female. | United States. Army. Signal CorpsHistory20th century. | United States. ArmyWomen History. | Women soldiersUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Women veteransUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Women soldiersLegal status, laws, etc.United States. | Sex discrimination against womenUnited StatesHistory20th century. | World War, 19141918Regimental historiesUnited States. | WomenSuffrageUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC D639.T4 C63 2017 | DDC 940.4/173082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016038111

for

James Christopher Shelley

CONTENTS

- Americas Last Citizens

- Neutrality Defeated, and the Telephone in War and Peace

- Looking for Soldiers and Finding Women

- Were Going Over

- Pack Your Kit

- Wilson Adopts Suffrage, and the Signal Corps Embarks

- Americans Find Their Way, Over There

- Better Late Than Never on the Marne

- Wilson Fights for Democracy at Home

- Together in the Crisis of Meuse-Argonne

- Peace without Their Victory Medals

- Soldiering Forward in the Twentieth Century

Over there, over there,

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming,

The Yanks are coming,

The drums rum-tumming

Everywhere.

So prepare, say a prayer,

Send the word, send the word to beware.

Well be over, were coming over,

And we wont come back till its over

Over there.

Hoist the flag and let her fly,

Yankee Doodle do or die.

Pack your little kit,

Show your grit, do your bit.

Yankee to the ranks,

From the towns and the tanks.

Make your mother proud of you,

And the old Red, White and Blue.

GEORGE M. COHAN, 1917

(UNOFFICIAL ANTHEM OF THE U.S. EXPEDITIONARY FORCES IN FRANCE)

SEVEN TOURING CARS, roadsters, and model T Fords constituted almost a traffic jam in the partially paved capital of windswept Montana in 1919. A local hero was coming home. The wide western sky was still luminous that June evening, when midsummers light bathed the town well past nine oclock and crickets took up their nightly chorus late.

Some in the party that wheeled jauntily up to the train station were veterans who had been discharged months earlier. Conspicuous with their colorful Victory Medals, the men drew up into an honor guard and saluted as the tall, dark-eyed woman stepped from the train in her blue army uniform after crossing five thousand miles of ocean, forest, and prairie. Thirty-year-old Merle Egan was a big towner and one of the best long-distance telephone operators in the United States even before she sailed to France. Now she was a local celebrity with her fitted suit, brass insignia, tan parade gloves, and cocky aviation cap. Merle smiled and waved, drained from her long ordeal but happy to spy the eager crowd and the copper dome of the state capitol. It meant she was home.

Montanans adored their girl, a soldier of unique distinction and one of the few women who was in the military service of the United States, the Helena Daily Independent boasted. Many patriotic Americans had done their bit to win the Great War, but Merle Egans bit was especially remarkable. She and two hundred other women had braved shot, shell, and submarines to operate the armys vital communications system overseas. General John Pershing recruited them personally. After the armistice, Merle commanded the switchboard for the epic peace conference at Versailles.

What wasnt clear as she shook hands with friends and admirers for nearly an hour on the crowded platform was where Merle Egan and other American women were going next. So much had changed in barely a year. The war had made women into soldiers and America into a world power. It had given the vote to women in Europe, then the United States. Only the week before, the U.S. Senate had approved the Susan B. Anthony Amendment after an exhausting seventy-year fight. Yet things were not entirely as they appeared. Despite the heros welcome, Merle would soon discover, to her great surprise, that the army denied she had ever been a soldier.

This wasnt what officials promised when they first went looking for women to run the telephones that American generals needed in order to command every advance or retreat. And Merle Egan was a woman who believed in promises. Little did she know that evening in Helena that the next leg of her journey, from army switchboard operator to womens rights organizer, would take sixty years.

Americas first female soldiers had been stationed throughout shell-shocked France as part of a compact branch of the U.S. Army known as the Signal Corps. The Signal Corps did not fire cannons, sink submarines, or bayonet invaders. Their job was to send messages. In March 1918, Stars and Stripes hailed the women who arrived during Germanys bombardment of Paris as Bilingual Wire Experts. They called them Uncle Sams Hello Girls.

Army nurses also served in uniform. Yet theirs was an altruistic occupation designed to alleviate the ravages of war, not to advance military objectives per se. The purpose of Signal Corps operators was to help the United States win its war. They were soldiers, not angels.

Technology set the course, propelling change in unexpected ways. In May 1917, the month after Congress declared war, General John Pershing sailed for France on a ship stuffed with equipment. Nicknamed Black Jack for having commanded an all-black regiment on the American frontier in the 1890s, Pershing made sure to carry not only standard gear but also the newest devices.

Military tackle had undergone a revolution since the last Indian wars only two decades earlier, when Black Jack rode with the Buffalo Soldiers of the Tenth Cavalry. Planes had replaced horses. Trucks had overtaken mule trains. Telephone wires had outrun semaphore flags and smoke signals.