First published in paperback in the UK in 2018 by

Intellect, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in paperback in the USA in 2018 by

Intellect, The University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street,

Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2018 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

Copy-editor: MPS Technologies

Cover designer: Jake Simonds-Malamud

Production manager: Faith Newcombe

Typesetting: Contentra Technologies

Print ISBN: 978-1-78320-874-6

ePDF ISBN: 978-1-78320-876-0

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78320-875-3

Printed and bound by Short Run Press Ltd, UK.

This is a peer reviewed publication.

Chapter 1

Home and Away

To be a mass tourist, for me, is to become a pure late-date American: alien, ignorant, greedy for something you cannot ever have, disappointed in a way you can never admit. It is to spoil, by way of sheer ontology, the very unspoiledness you are there to experience.

David Foster Wallace (2009)

The first thing we see as we travel round the world is our own filth, thrown into the face of mankind.

Claude Lvi-Strauss (1992: 24)

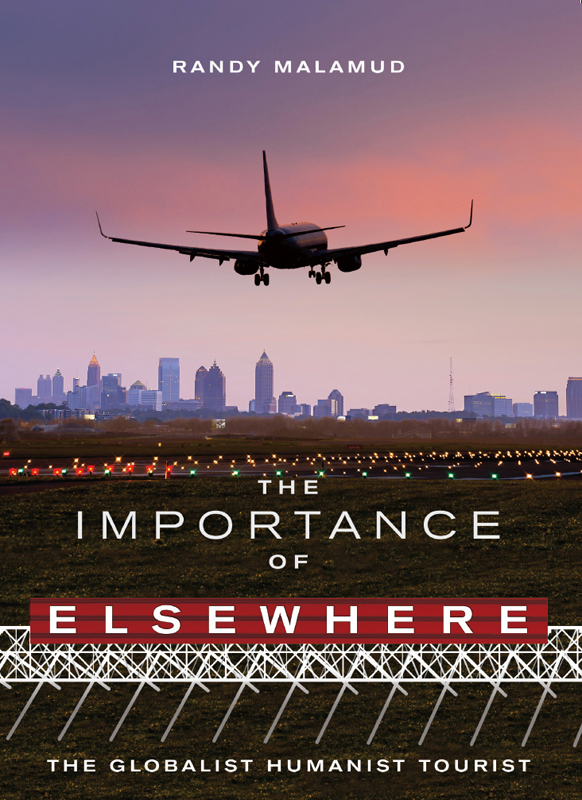

T raveling begins with basic, pragmatic questions: where are we going, how long will we stay, how much will it cost, what will we do? Alongside these, I want to pose some more theoretical and philosophical inquiries: What does travel mean? How and why do we do it? How do we think (and talk and write) about our travels? What experiences render us changed (and how) when we return? How does traveling intersect with culture cultural artifacts, cultural experiences, cultural appreciation? In this difficult moment for the world, is traveling really fundamentally important, or is it just an escapist indulgence reflecting privileged hedonism? How has travel changed in this globalist era, and what do we hope to achieve by stepping into globalism?

Stepping into globalism may sound lofty, but it fittingly captures my ambitions as a traveler. Globalism is a vast and daunting concept: corporate, institutional, hardly relevant (as most people understand the term) to the mere traveler, the mere individual. My own mere humanism involves reading a great deal, writing a bit, and moderating semiformal discussions with two dozen young people every Monday and Wednesday about such matters as ekphrasis, Imagism, and intertextuality. How presumptuous it must seem to suggest that my cerebral literary credentials provide any authority to represent myself and my work as globalist.

The trope of globalism is overwhelming: billions of people, trillions of dollars, innumerable inventories of soybeans, or microchips, or some other kind of widget. Globalism means industry, finance, technology, transportation, health, militarism, and diplomacy, all ensconced in a technocratic vocabulary of geopolitics and multinationalism infelicitous to those of us who engage the world on a more human scale and in a more mellifluous timbre. As globalism became a twenty-first-century buzzword in academia (and in commerce, media, activism, and most other realms of civic participation), have we writers, artists, philosophers, and other assorted aesthetes fallen out of the loop? Globalism seems to connote a world where humanists should fear to tread too large, too complicated for our simple and delicate engagements. Our everpresent anxieties impel us to worry that we are out of our league when it comes to such macrocosmic, important, real-world phenomena. A globalist conveys the sense that I am large, I contain multitudes, although the astute humanist will recognize that this phrase comes not from a president or a CEO but rather from Walt Whitman: one of ours.

Global signals urgency, and often danger: global terror, global contagion, global warming. Global systems and problems global trade, global health, global security operate in a realm far beyond the reach of humanism. Far is the key obstacle here: globalism is large, and its components are distant. Humanism, on the other hand, is proximate, intimate, local, contained it takes place, to be tautological, on a human scale. The globe is a colossal realm though in another sense, a globe itself (an office desk globe, or a free-standing classroom globe) is not all that large: perhaps only a foot or two in diameter. What a globe represents, as a scale model of our planet, is indeed large. That facet, that fact of representationality, suggests the humanists ingress: we are clever at understanding and grappling with representations of things.

In the mid-sixteenth century, the Latin word globus (a round, three-dimensional structure) produced an English cognate, globe: a spherical representation of the earth with its map on the surface, often fixed to a stand which may be rotated on a vertical axis. Not long after the word appeared, a London dramatist of some renown founded a theater he called The Globe, featuring plays where a few dozen actors, with the aid of some colorful costumes, minimal props, a bit of background music and dancing, and some highly imaginative dialogue, created a dazzling array of stories about not just England but also Verona, Egypt, Scotland, Denmark, Troy, Vienna, Rome, Harfleur, Paris, Navarre, Bohemia, Venice, Athens, Tyre, Sicily, Cyprus, Padua, and, for the most engrossing global travel narrative of his age, a remote enchanted island of indeterminate geographic location.

You may guess where this is leading.

It is indeed possible (and also fun!) to transgress an implicit proscription by becoming a globalist humanist. I have done it. Traveling to China and Dubai, Iceland and Budapest, Costa Rica and Lisbon, I have ticked off more countries than I ever thought I would 40 at present, and still tramping the perpetual journey (Whitman again) across the globe.

The expedition embodied in this book grows out of my own personal and intellectual excursions. My approach is autotheoretical: autobiographical writing that exceeds the boundaries of the personal, as Maggie Nelson, author of The Argonauts, characterizes it, deploying [ones] own experience as an engine for thinking that spins out into the world (Lorentzen). I celebrate myself, and sing myself, and theorize myself. Following the disciplinary pathways that have shaped me, I am drawn to analyze the metaphorical and semiotic strata that overlay, or underlie, the practice of traveling. But I value equally the simple, colorful, and sometimes mundane details of my trips how I got there, what I saw, and enjoyed, and ate, and learned before it was time to return home.

My itineraries often start with museums. After I have seen as many of them as I can stand, I drop in on authors homes, arthouse cinemas, and architectural spectacles. I visit historical sites, famous and obscure, and also touchstones of urban design: the Paris arcades, Londons and Milans canals, Warsaws socialist showpiece Marszakowska Dzielnica Mieszkaniowa (MDM) sector, Tel Avivs art deco district. Language permitting, I attend theaters and cabarets. Next, food venues (markets, ethnic enclaves, cafs, street food) and neighborhoods known for fashion, design, antiques and collectibles, murals and other public art. I go shopping (for the purposes of cultural anthropological investigation, of course). I like to stroll through riverwalks and quays, business districts, parks, gardens. I take organized walking tours, and also impromptu ad hoc excursions that is, I get blissfully lost. I enjoy spending much longer than necessary in train stations and airports taking mental notes as I watch other people at the beginnings and endpoints of their travels. Public squares are great places for humanist fieldwork, as are libraries. I tour a countrys parliament building and supreme court whenever possible; banking museums, too, I find, are usually unexpectedly fascinating. I visit places that manifest extraordinary beauty Bruges, the ancient city of Petra, the hills looming over Lake Como, any gothic cathedral as well as places that embody a less famous but still profound appeal. I enjoy both the usual tourist sites and ones that are off the beaten track; places with plaques and statues, and places without; things that millions before me have Instagrammed ad absurdum, along with things I seem to have happened upon on my own, accidentally, serendipitously.