AFRICAN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIES

OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Volume 3

THE BASUTO

THE BASUTO

A Social Study of Traditional and Modern Lesotho

HUGH ASHTON

First published in 1952 and as a second edition in 1967 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1967 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-48710-9 (Volume 3) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-351-04306-9 (Volume 3) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

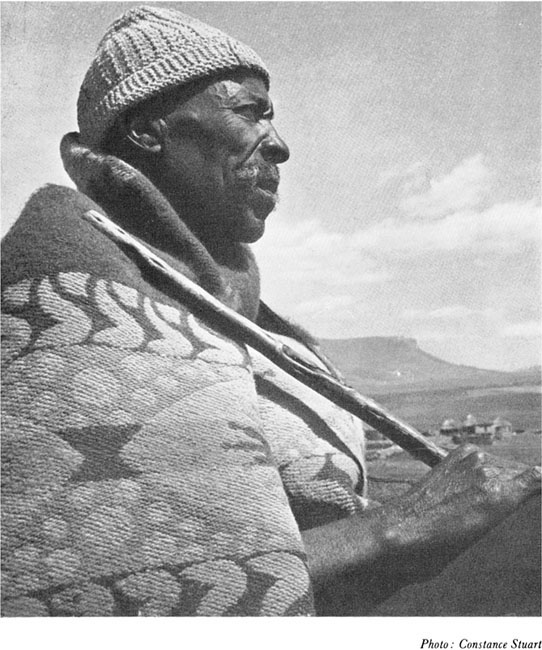

A Mosuto looks over the Lowlands

THE BASUTO

A SOCIAL STUDY OF TRADITIONAL

AND MODERN LESOTHO

by

HUGH ASHTON

Second Edition

Published for the

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by the

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

1967

CONTENTS

Oxford University Press, Ely House, London W.1

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON CAPE TOWN SALISBURY IBADAN NAIROBI LUSAKA ADDIS ABABA BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA KUALA LUMPUR HONG KONG TOKYO

New material in this edition

International African Institute 1967

First published 1952

Second edition 1967

Printed in Great Britain

LIST OF PLATES

A Mosuto looks over the Lowlands Frontispiece

Facing page

N INETY years ago, Eugne Casalis (of the Socit des Missions van-geliques, Paris) was the first to write a full account of the customs and beliefs of the Basuto, an interesting and forthcoming Bantu people living in South Africa. He was in a unique position to do so, and being one of the earliest Europeans to live amongst them, he could observe and describe their culture before the disrupting influences of Western civilization began to take effect. He was followed some fifty years later by two more of the French missionaries to whom Basutoland owes so much, Dieterlen and Kohler, who wrote on the Basuto of Yesterday and To-day in the Livre dOr published in 1912, to celebrate the missions Golden Jubilee. About that time appeared two historical publications, Ellenberger and MacGregors collection of tribal traditions and Lagdens two-volume political history. Since then, save for Duttons slight sketch, there have been no comprehensive descriptions of the Basutos changing culture, although there has been a spate of articles on different subjects. Of these the best include those written by Laydevant, another French missionary, but of a different persuasion from his predecessors, and some admirable technical surveys such as Stapless on the ecology and Stockleys on the geology of Basutoland. In this book I have attempted to synthesize all this published material together with the results of my own field work, and to present an all-round picture of the Basuto as they are to-day.

Casalis wrote his book to arouse his fellow-countrymens interest in the Basuto with a view to enlisting their material support for the work of the mission in its far-flung foreign fields. I, too, hope to interest the general public, not for any particular institution or policy, but for the sake of mutual understanding and enjoyment. I think it is fun to know how other people live, think, and tackle the fundamental human problems of education, sex, earning a living, law and order; but I also believe it is of paramount importance for the sake of peace and mutual accommodation, in a race-ridden society such as we have in Southern Africa, that there should be mutual respect and understanding. It is comparatively easy for the African to learn about the European way of lifein fact he can scarcely escape getting some ideas on the subjectbut the European has to make more of an effort as he has little direct contact with African life and little access to the available literature. I have therefore tried to make this a straightforward and readable account of the Basuto way of life and I must seek the indulgence of my fellow-anthropologists for eschewing jargon and adhering to common forms of spelling such as Basuto (instead of the technically correct but awkward-sounding BaSotho) and for omitting all theoretical discussion.

There are, however, two theoretical points that I should have liked to work out in detail. One is that culture is not a homogeneous, integrated whole. There is obviously a central pattern which gives a particular culture its general character and distinguishes it from other cultures; but it is not a rigid pattern nor yet all-embracing. It has all sorts of deviations and exceptions, some of which are due to individual aberration or choice, to changes of time, place or circumstance, while others are due to differences between whole sections of the community. This applies to the Basuto. There is undoubtedly a Basuto culture as distinct from the culture of the Zulus or the Bechuanaquite apart from that of Europeansbut it varies in detail from one area to another, from one group or one individual to another. Up in the mountains the Batlokoa still observe many of the old Basuto customs described by Casalis, and are closer than other Basuto to the traditional culture of pre-European times; but even here, there are wide variations between chiefs and commoners, rich and poor, educated and untutored; in the lowlands a few Basuto still follow the old ways, but most have left them and are living by a hotchpotch of old and new customs, and some have largely adopted European customs and modes of thought.

The second point concerns the theory that the function of some institutions and aspects of culture is to satisfy certain basic human needs: that systems of magic and religion provide reassurance regarding future life, allay mans fear of death and give him confidence to face the natural forces of storm and drought, pestilence and famine; the economic system directs his efforts to feed and clothe himself; the political and judicial systems provide for social order and stability. When societies were in a state of equilibrium, as many primitive ones were before the coming of the white man, it could reasonably be assumed that these systems effectively achieved their objects. Now that most primitive societies are changing and unstable, such an assumption is no longer valid and it behoves the anthropologist to assess the effectiveness of these institutions and aspects of culture: to judge the extent to which the economic system does satisfy the peoples material needs, in terms of health, physical development, and decent living; how far their political institutions are satisfactory, judged by such indices as stability of family and social relations, expressions of contentment or misery, grumbling and complaint, and the prevalence of crime. These are not easy assessments to make and many of them require the many-sided approach of a team of experts; but they should be attempted and to a limitedtoo limitedextent I have tried to assess the worth of Basuto economic and judicial institutions.