The

Baby

on the

Fire

Escape

CREATIVITY, MOTHERHOOD, AND THE MIND-BABY PROBLEM

Julie Phillips

To Kit, Jan, Eise, and Jooske

My mother, my husband, my children

Contents

[is] a figure that disrupts or interrupts our notions of subjectivity. (LISA BARAITSER)

... that motherhood is an undiscovered country in the literary sense, one we must venture into lest our experience [go] unrecorded. (SARAH RUHL)

P ICTURE AN ARTIST OR WRITER at work, and you probably imagine sustained, solitary concentration. Proust, scribbling in bed in his cork-lined room. Yeats, descending from his tower, encountering his two children, and asking, Who are they? Wittgenstein, who is said to have eaten nothing but Swiss cheese sandwiches for weeks on end because even changes in the flavor of his food disturbed his thoughts.

The artist may be in the midst of family life but obsessively at work, like Henri Matisse, whose painting pulled him in like a vortex. He could think of nothing else, his daughter said. The creator may be an art monster, Jenny Offills term for the creator who lives only for the work.

The great writer may be a detached observer, a flneur soaking up scenes of city life. If natural beauty is his subject he may write alone in a cabin in the woods or wander lonely as a cloud, enjoying the bliss of solitude. She may agree with the poet Mary Oliver that a lot of time to be a genius, you have to sit around so much doing nothing, really doing nothing.

A typical picture of a woman with children is of someone whose children are constantly breaking in. Perhaps she has shut herself into a room to write. Her kids have promised not to knock or to make noise. But she knows they are there because they are lying down and breathing under the door. Adrienne Rich longed in vain, amid of her thumb / a giant stopper in my throat.

In place of the solitary flneur, imagine Naomi Mitchison in a London park, writing on a board balanced on her pram. Think of Shirley Jackson making plot notes in the kitchen while dinner was on the stove; Toni Morrison driving to work with a pad of paper in the car so that she could write whenever the traffic slowed. Here the act of writing is not continuous but provisional, contingent, subject to disruptionand yet the words are still coming and the work is getting done.

T HE DIVISION BETWEEN mothering and creative work once seemed (more or less) absolute. Sylvia Plath feared that a woman must physically attractive and patient and nurturing and docile and sensitive and deferential... contradicts and must collide with the egocentricity and aggressiveness and the indifference to self that a large creative gift requires in order to flourish, Susan Sontag said, overstating things as usual, but the expectation that women (more than men, even now) should be ever present for their children does compete with creative selfhood.

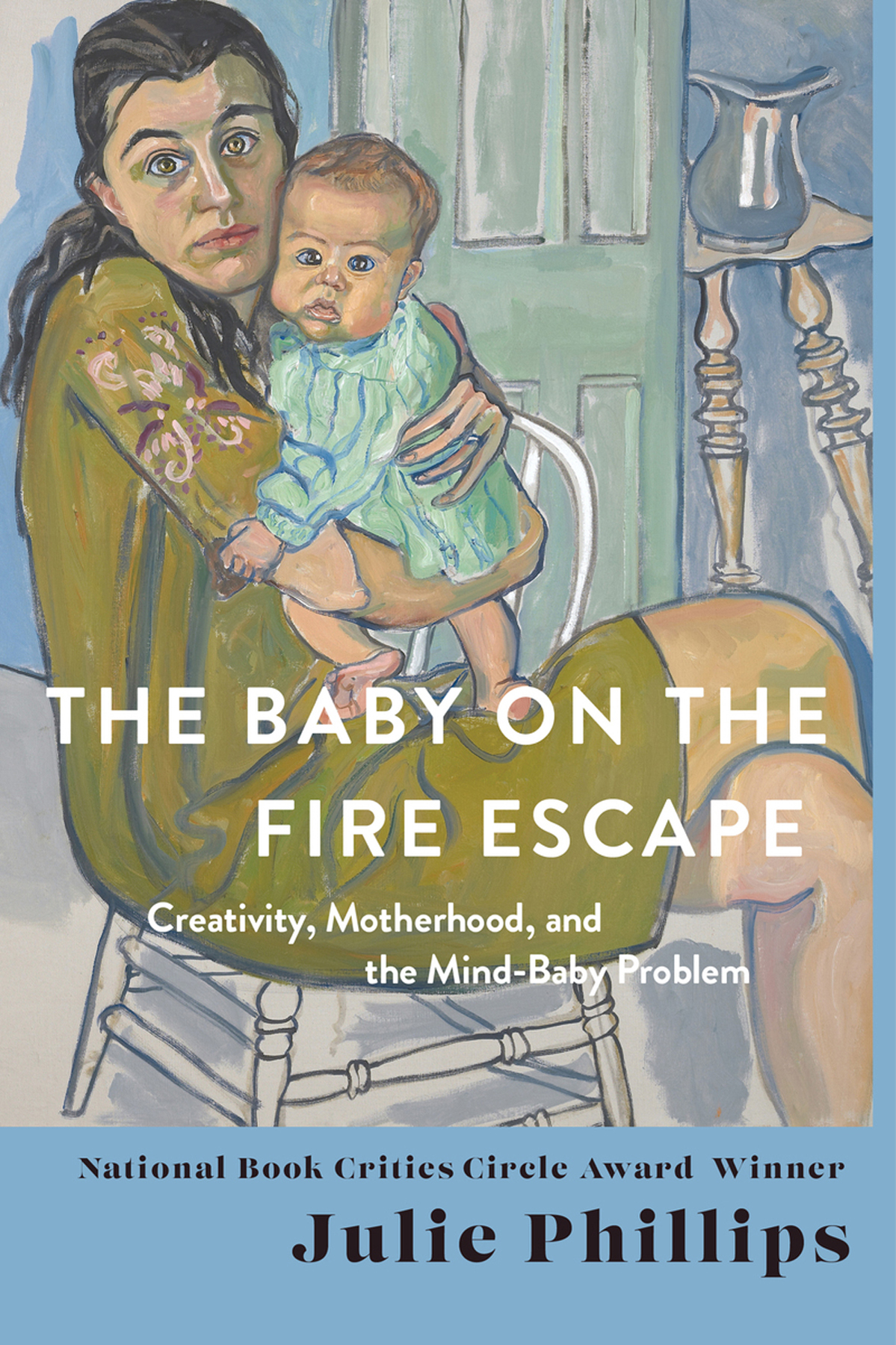

Sometimes mothers had trouble giving themselves permission. Alice Neel said that until she received a major retrospective in her seventies, felt in a sense that I didnt have a right to paint because I had two sons and I had so many things I should be doing and here I was painting. Sometimes the judgment came from others: Neels in-laws claimed, on no evidence, that she had once left her baby on the fire escape of her New York apartment when she was trying to finish a painting. Its a vivid image of the dangers, in their mind, of trying to do two things at once.

Maternal bliss conspires with maternal guilt to erode creative work. Margaret Mead: [Its] for your child has a way of obliterating whatever you used to think you loved.

In 1962 Olsen could still state that almost no mothers, or any other persons, had written books that would endure. But in or about that same year, the careers of women with children were beginning to flourish, not just in ones and twos but in numbers big enough to matter. Mothers found ways to do their work, and were recognized for it: Doris Lessing won the Nobel Prize; Ursula K. Le Guin was awarded the National Book Medal, Americas highest literary honor. Alice Walker won a Pulitzer and sold millions; Audre Lorde opened a conversation around intersectionality. Angela Carter was acknowledged as one of the defining literary voices of twentieth-century Britain, and Susan Sontag as one of the great English-language critics. Alice Neel saw her art accepted into the canon.

Ive tried in this book to trace the course of that change. Ive tried to find out what mothering plus creativity looks like, not just in the first few years, but as part of a life story. What does it mean to create, not alone in a room of ones own, but in a shared space? What kinds of work have come out of that space? What is the shape of a creative mothers life?

T HIS WAS MY PLAN : to explore the blank spot on the map where mothering and creativity converge. I had never been able to convey the full power of my own life as a mother: I remember how empty even the simple sentence I have two children felt in comparison to the experience, as though I was recounting a dream that made no sense in daylight. Because I didnt have words, I wanted others to speak for me. In investigating the lives of great women, I hoped to see my own experience with new eyes.

That blank spot should have told me something. The more I read and wrote, the more the place where mothering and creative work come together seemed not to be an intersection of identities, but a negative space, an impossible position. I read brilliant first-person accounts of mothering but couldnt see patterns or a path. The stories of my subjects lives as mothers wouldnt hang together. When I looked at the work, the mothering vanished, and vice versa. When I read essays, memoirs, and stories, I found contradictions, fragments, anecdotes, scraps of enlightenment. I encountered what psychoanalytic theorist Lisa Baraitser calls the of how... intellectual and maternal labor appear to cancel one another out.

Parenting affects, and is affected by, each persons circumstances, and is affected too by race, resources, sexuality, family relationships, (dis)ability. Not all mothers have given birth; not all end up raising their children. The women I wanted to write about came to mothering by different paths, did or didnt have a partner, were older or younger, had more or less money and support. They became pregnant by accident or by choice, fostered a teenager, confronted infertility, lost a child. They admitted anger and pain, rejected stereotypes (superwoman, angel in the house), explored maternal ambivalence.

But where is mothers creative self? Do mothers have inner lives? What is the subjective experience of being a mother, and why, despite a steadily growing body of writing on the phenomenology of mothering, does it still seem, on a deeper level, so unnarratable, undramatic, everywhere in practice, but in theory nowhere?

I started saying I was exploring maternal subjectivity. That got some peoples attention, especially academics, or at least it didnt make their eyes glaze over the way Im writing about mothers did. Proposing mother as a subject position surprises people, and it also, on the evidence, baffles them. Over and over again my friends forgot the subject of my book, until I started to wonder if my blank space on the map was unthinkable, beyond memory.