The Grover E. Murray Studies in the American Southwest

Also in the series

Brujeras: Stories of Witchcraft and the Supernatural in the American Southwest and Beyond , by Nasario Garca

Cacti of Texas: A Field Guide , by A. Michael Powell, James F. Weedin, and Shirley A. Powell

Cacti of the Trans-Pecos and Adjacent Areas , by A. Michael Powell and James F. Weedin

Cowboy Park: Steer-Roping Contests on the Border , by John O. Baxter

Dance All Night: Those Other Southwestern Swing Bands, Past and Present , by Jean A. Boyd

Deep Time and the Texas High Plains: History and Geology , by Paul H. Carlson

From Texas to San Diego in 1851: The Overland Journal of Dr. S. W. Woodhouse, Surgeon-Naturalist of the Sitgreaves Expedition , edited by Andrew Wallace and Richard H. Hevly

Grasses of South Texas: A Guide to Identification and Value , by James H. Everitt, D. Lynn Drawe, Christopher R. Little, and Robert I. Lonard

In the Shadow of the Carmens: Afield with a Naturalist in the Northern Mexican Mountains , by Bonnie Reynolds McKinney

Javelinas: Collared Peccaries of the Southwest , by Jane Manaster

Little Big Bend: Common, Uncommon, and Rare Plants of Big Bend National Park , by Roy Morey

Lone Star Wildflowers: A Guide to Texas Flowering Plants , by LaShara J. Nieland and Willa F. Finley

Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker , by Paul H. Carlson and Tom Crum

Pecans: The Story in a Nutshell , by Jane Manaster

Picturing a Different West: Vision, Illustration, and the Tradition of Austin and Cather , by Janis P. Stout

Texas, New Mexico, and the Compromise of 1850: Boundary Dispute and Sectional Crisis , by Mark J. Stegmaier

Texas Quilts and Quilters: A Lone Star Legacy , by Marcia Kaylakie with Janice Whittington

The Wineslinger Chronicles: Texas on the Vine , by Russell D. Kane

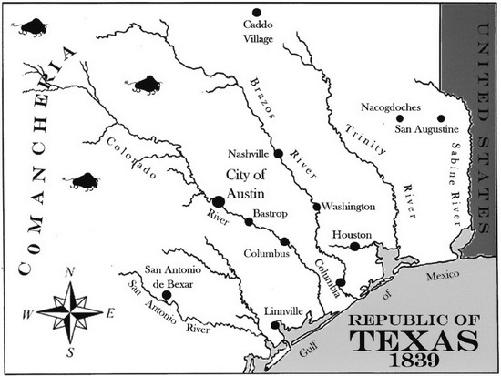

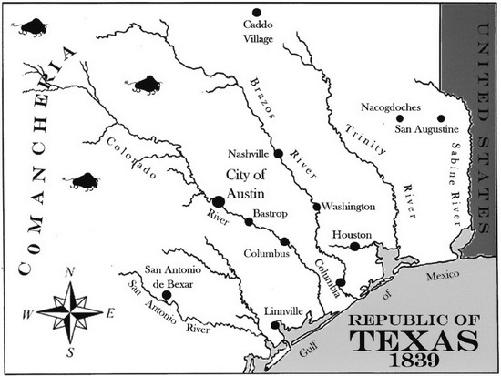

Map of Austin area, 1839. Courtesy of the author.

TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY PRESS

Copyright 2013 by Jeffrey Stuart Kerr

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage and retrieval systems, except by explicit prior written permission of the publisher. Brief passages excerpted for review and critical purposes are excepted.

This book is typeset in Monotype Amasis. The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997).

Designed by Kasey McBeath

On the cover: (top left) Mirabeau Lamar, courtesy the San Jacinto Museum of History, Houston, Texas; (top right) Sam Houston, courtesy the George Eastman House; (center) detail from Austins original city plan, c. 1839, courtesy the Texas State Archives; (bottom) view of Austin, c. 1860, courtesy the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, the University of Texas at Austin, CN12190.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kerr, Jeffrey Stuart, 1957

Seat of empire: the embattled birth of Austin, Texas / Jeffrey Stuart Kerr.

pages cm. (The Grover E. Murray Studies in the American Southwest)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-89672-782-3 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-89672-783-0

(e-book) 1. Austin (Tex.)History. 2. TexasCapital and capitolHistory.

I. Title.

F394.A957K475 2013

976.4'31dc23 2013011214

Printed in the United States of America

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 / 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Texas Tech University Press

Box 41037 | Lubbock, Texas 794091037 USA

800.832.4042 | ttup@ttu.edu | www.ttupress.org

In memory of the men, women,

and children forcibly evicted from and carried

to frontier Austin and its territory

CONTENTS

ix

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

ILLUSTRATIONS

Introduction

W ant of political unity is the one consistent theme threading its way through the fabric of early Anglo-Texan history. Seemingly no action occurred without bitter squabbling beforehand and angry finger-pointing after the fact. That an independent Texas emerged from those hectic days, given the divided goals and loyalties afflicting the leaders of the Texas Revolution, is nothing short of remarkable.

A split command at the Alamo certainly added little to the effectiveness of its garrison as a fighting unit. Then, after the Alamo disaster, General Sam Houston drew charges of cowardice as he led his army on a tactical retreat toward the east. Realizing that two of his officers had no intention of obeying orders to retreat beyond the Brazos River town of San Felipe, he instead ordered them to stay at the Brazos to delay the enemy advance. Bickering continued right through the decisive Battle of San Jacinto. Many officers and men in Houstons army believed strongly that Houston had turned toward Santa Annas army instead of retreating into Louisiana only because they had forced him to do so at a critical road junction. Mirabeau Lamar, who figures prominently in this book, claimed that the successful charge against the Mexican camp had been launched over Houstons objections. For years after the battle men exchanged heated words over whether Sam Houstons actions had constituted cowardice or heroism. The fact that few minds were changed by these arguments planted the seeds for the growth of two political camps in the na-scent republic.

Victory in the revolution did little to quell strife. Santa Annas life would have ended in front of a Texian firing squad if many, Mirabeau Lamar included, had had their way. When President David Burnet named Lamar Commander-in-Chief of the army, enough soldiers balked that Lamar quickly resigned. Burnet himself resigned not long thereafter due to plausible threats of a military overthrow. One of Sam Houstons initial actions as the first elected President of the Republic, therefore, was to begin furloughing as many soldiers as possible.

The 1836 election that installed Sam Houston as President of the Republic also ushered Mirabeau Lamar onto the national stage as Houstons vice president. A more unfortunate pairing can hardly be imagined. Tall and athletic, outgoing, and at the time still prone to drunkenness, Houston struck Lamar as an overrated demagogue. Short and squat, taciturn, and sober, Lamar impressed Houston as a bumbling fool. Although they may have encountered each other along the march to San Jacinto, the two men first came into more direct contact on the battlefield itself. When Lamars bold action during a skirmish the day before the battle saved two lives, General Houston offered him command of the artillery. Lamar declined. Later, though, when several cavalrymen and officers insisted that Lamar lead the cavalry in the upcoming battle, he agreed to do so. Houston later expressed puzzlement rather than annoyance at all this, but it was an inauspicious start to the pairs relationship.