To the men and women whose work behind the scenes makes possible the flights of humans into space.

Foreword

Alfred Worden

Apollo 15 Astronaut

I was born and raised, along with five brothers and sisters, on a small farm in Michigan. By the time I was twelve I was working full days in the fields and milking cows. This was just after the Great Depression and at a time before space travel, before jet engines, in a year when the world's most sophisticated rockets were generally not getting much higher than a couple of hundred feetif they didn't blow up first.

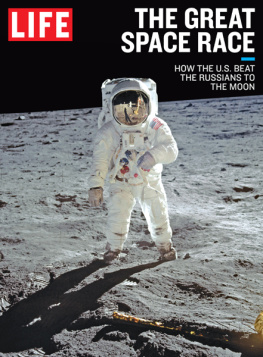

It would have been hard for me to imagine that only two decades after leaving that farm, I'd be heading into space on a rocket as large as a forty-story buildinga rocket so huge that I was a long, long way above the ground even before we lifted off. It was so tall, in fact, that it was not a noisy ridebecause the noise was generated about three hundred feet below us, about the length of a football field. But I could feel the force of rocketing into orbit. As the fuel burned out of the first stage and the vehicle became lighter we accelerated to about 4 g's, which was like four people sitting on me, and it was not pleasant. The Saturn V rocket, which took three of us all the way to the moon, was an incredibly accurate machine, operating to the precise split second planned. Our crew spent a lot of time training in case something went wrong during launch: for example, if the engines quit, an escape tower would pull us away to safety. But we never needed that trainingthe rocket worked just fine. I even wrote a couple of poems about that beautiful, majestic Saturn V rocket.

The Apollo 15 mission that I flew has been called the high point of human exploration. The rocket launch was just the beginning of the lunar journey, but I'd already taken a long journey in my career to get to that point.

As a teenager, working on that farm, I realized that farming was not what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I decided that I wanted to go to college, and I ended up with the equivalent of an engineering degree from the United States Military Academy at West Point. I still didn't have any real interest in flying or rocketry, but decided to go into the air force because I heard that the promotions were quicker there than in the army. I was wrong about that, but in the process I found out something else. I got really interested in how to fly an airplane, especially flying on instruments. I soon realized that I had a gift for it; I could do it pretty well. Flying airplanes is not the same as flying rockets, but it wasn't long until rocketry also became part of my career.

My first real interaction with rockets was when I was assigned to an air defense squadron in Washington DC. We were flying live missiles and rockets on those aircraft in defense of the nation's capital, and without a lot of flying time available I got really interested in the maintenance activity going on. Soon, I was running the section: we rebuilt the armament shop and turned it into a modern repair shop like you see today. Air Defense Command liked it so much they wanted me to head up a program to help other fighter squadrons do the same thing. Instead, I went back to college, this time to learn about guided missiles. That led me into being a test pilot the top of the heap in aviation.

I ended up teaching as well as flying, at the test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base. For a while I was training the pilots on the X-i5 rocket plane in landing techniques. I was even training astronauts like Gene Cernan and Charlie Bassett in a zero-gravity simulator that we had. I wrote and taught a number of the courses in spaceflight that the test pilots had to pass; my transition from flying planes to flying rockets was getting ever closer.

Although it was always something to work toward, I hadn't thought about being an astronaut; when I became a test pilot, there just weren't any openings. But after about a year and a half, they had a selection. I'd always thought of it like winning the lotteryit would be nice, but was never going to happen. Too many other people wanted it. We even fooled someone else in our squadron into thinking he was selected. We kept that prank going for about two weeks until we told the poor guy. I was very fortunatewith the right combination of college work and test pilot experience, I made the cut.

I soon realized that being a test pilot, the top of my profession, counted for nothing in the astronaut circle. I was one of the new, green kids on the block. I understood the gameI had to get on a rocket and make a flight before anyone would consider me a "real" astronaut. It was pretty humbling. Individually, I knew I had a lot of very hard work ahead of me, and collectively our new astronaut group really applied itself to the mammoth task ahead. During the first week, while undergoing instruction in orbital mechanics and rocket trajectories, we came to the realization that we could probably do a better job training ourselves. Our recommendation was accepted and a period of successful self-instruction began. Soon, I was working on the Apollo Command Modules as they were being built, and got to know their workings probably better than anybody.

I was on the support crew for Apollo 9, on the backup crew for the Apollo 12 moon landing mission, and then flew on Apollo 15. It was a lot of work, but a lot of fun too. We were launching so frequently there was not a lot of time between missions. Yet by the end of the training we felt that we could handle any malfunctions, any problems.

Our Apollo 15 mission truly was exploration at its greatest. Unlike previous lunar missions, where they only had limited time, we had better spacesuits, an upgraded Lunar Module that allowed a longer stay, and even a lunar rover, allowing my two crewmates to drive around on the surface. This lengthier missiontwelve days in spacealso meant that I was in lunar orbit longer than anyone had ever been before. After that Saturn rocket took us to lunar orbit I spent three days alone, a quarter of a million miles from earth, mapping the surface of the moon and operating remote sensors from the orbiting Command and Service Module.

I would have liked to have made a lunar landing, no question about that. But I was very happy where I was. In my thirty-five solo orbits of the moon, I was able to thoroughly observe a quarter of its surface, compared to the small area my crewmates were able to traverse after landing. It was a long way from home, and the only thing connecting me to earth was the radio. It was even a little scary. But after four days in a crowded spacecraft with two other guys, it was certainly nice to be on my own. If it wasn't for enormous and precisely functioning rockets, we would never have been able to achieve this incredible scientific exploration. But I was always aware of the risks we were taking. Before the launch, I talked to my family, and I remember thinking that this might be my goodbye: If the rocket malfunctioned, I might not be coming back to see them again. We astronauts accepted the risk because the rewards were worth it. My only real concern was if something did go wrong, I didn't want to be the one who had caused it.