THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

MIKLS BETHLEN

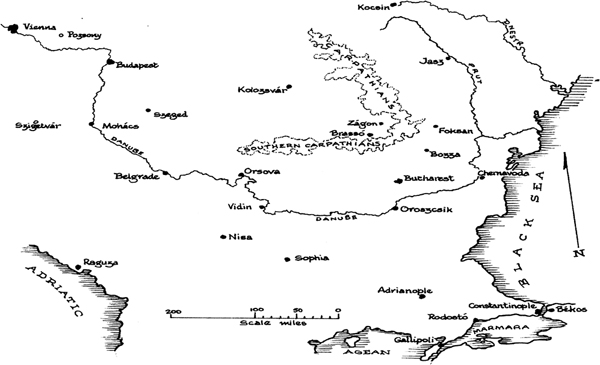

The Bethlen family was an ancient noble house of considerable wealth and influence in Transylvania. The earliest recorded member of the family is one who died while studying in Paris in 1184; such was the familys status even then that the king of Hungary was personally notified of the sad event. Over the years the Bethlens provided many a distinguished man to public life--Count Istvn, Prime Minister of Hungary 1921-31, was the last Bethlen to hold high office--among them Privy Councillors, Chief Justices, Fispns, military commanders and Chancellors of Transylvania. Their most famous member, Gbor Bethlen (1580-1629), ruled as Prince of Transylvania from 1613 and was elected King of Hungary in 1620, although he was never crowned. The writer of this autobiography, Count Mikls (born 1642), was a general in 1682, Privy Councillor in 1689, Fispn in 1690 and Chancellor in 1691, after an excellent education (including travel and study in western Europe) and a distinguished career in public life. He then clashed with General Rabutin, from 1696 the Austrian Commander in Chief in Transylvania, which led to his arrest and imprisonment on a charge of treason in 1703.

His autobiography, one of the most extensive of the literary memoirs that came from Transylvania at this period (among them the Letters from Turkey of Kelemen Mikes and Metamorphosis Transylvaniae of Pter Apor, both published by Kegan Paul in Bernard Adamss English translation), was written in prison and under sentence of death in Hungary and Austria. Transferred to Viennese confinement in 1708 and pardoned by Emperor Charles III in 1712, Bethlen was never allowed to return to Transylvania, spent his last years in relative freedom in Vienna, and died in 1716.

First published in 2004 by

Kegan Paul International

This edition first published in 2010 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0972-4 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0972-3 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Foreword

As one to whom the gate of eternity stands open, in view of my sixty-six years and the sentence of death that has been pronounced upon my head, perhaps I have not as many days or hours left as I have lived years. Thus Mikls Bethlen describes his situation in of his Introduction. The prospect of uncertainly imminent decapitation puts the autobiographer under pressures which it is hard to imagine.

Born into an ancient aristocratic Hungarian Transylvanian family, Bethlen rose to high office in the course of a turbulent life, and was cast down again, as was almost de rigueur in the society of the time and place. His account of his life presents details of his education, his studies and travels abroad (including a visit to England and a meeting with Charles II) and his ever deeper involvement in the events of the last years of the independent Principality of Transylvania and the early years of Habsburg rule. His insights--fruit of intimate personal knowledge--into the leading characters around him, such as Prince Mihly I, Princess Anna Bornemisza and Mihly Teleki, are uniquely revealing, as are those into the complex interrelationship of Transylvanian, Austrian and Turk, while the details of his family life--often left to be read between the lines--the financial problems that never quite left him, and the influence on all this of his sternly Calvinist background make for fascinating reading.

* * *

Bethlens own Introduction must be the longest in literary history, but it was clearly not intended at the outset to be such, and the circumstances of its composition are largely responsible. Writing in a month of tedium in May and June 1708 while in prison at Eszk en route from prison in Szeben to prison and execution in Vienna, Bethlen allows himself to digress, to stray, one might almost say, into a rambling analysis of the Calvinist mindset that had governed his career. The proposed Introduction seems at first to end with he ranges through contemporary philosophy and theology, touching on honour and reputation, displaying familiarity with both the Latin Classics--Ovid, Seneca, Cicero, Tacitus, Juvenal and Vergil are quoted--and the work of thinkers and scientists of his own era--Descartes, Newton and Galilei to name but three. He dips into cosmology with a discussion of time and eternity, into astronomy with comments on the relative merits of the solar and lunar years--oddly, he seems to be still using the Julian calendar--and into medicine with dietary advice and comments on the treatment of ailments. His chemistry, with its four elements, is medieval, but the physiology by which he analyses the response to a stimulus is surprisingly advanced. His theology is less than easy for modern man to grasp, while for much of what he says on most subjects he claims biblical authority, often backing his claims with quotations from scripture that reveal an encyclopaedic knowledge.

The Introduction is therefore intensely scriptural, setting the tone for what is to come. In translating it I was at first strongly tempted to use only --in many respects a perfectly good introduction--but the following chapters reveal so much of the character of the author and his psychological fabric that although the modern reader may well wonder quite where it is leading on more than one occasion he will be amply rewarded by following Bethlens cultural trail. This is a valuable, possibly unique, study in introspection from a philosophically alien time and place.

Bethlen is not immediately clear in the Introduction about the audience for which he writes. He is explicit at the end of of the Introduction, however, and elsewhere in the work, it is stated firmly that the intended principal beneficiary of the autobiography is Jzsef.

* * *

Book One deals with Bethlens ancestry, early life and education, ending with his return to Transylvania after study and travel abroad, and his first experience of public life. He makes little mention of his mother, who died early in 1661 when he was twenty. His father, however, was a man of no small importance, serving from 1659 as Chancellor of Transylvania, and despite his comparatively modest means was enlightened enough to spend as much as he could afford on his two sons education. Curiously enough, the first known member of the Bethlen family was one who died while studying in Paris in 1184, so young Mikls was in a long family tradition! A series of private tutors met with varing degrees of success until he was eventually placed with Pl Keresztri and, after Keresztris death, with Jnos Csere Apczai, under both of whom his father too had studied. The courses that he followed were essentially medieval, with rhetoric, logic, philosophy and poetics figuring largely, and were conducted in both Hungarian and Latin. Such mathematical instruction as he received was very basic. Under his last two tutors he became a precocious youth, a ready debater on theological subjects who attracted the attention of senior clergy and even the Prince himself at quite an early age.