Copyright 2005 by David G. Campbell

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Campbell, David G.

A land of ghosts : the braided lives of people and the forest in far western Amazonia / David G. Campbell

p cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-395-71284-x

1. Indians of South AmericaBrazilAcreHistory. 2. Indians of South AmericaJuru River Valley (Peru and Brazil)History. 3. Indians of South AmericaJuru River Valley (Peru and Brazil)Social conditions. 4. Indigenous peoplesJuru River Valley (Peru and Brazil)Ecology. 5. Rain forest ecologyJuru River Valley (Peru and Brazil) 6. EthnobotanyJuru River Valley (Peru and Brazil) 7. Endangered ecosystemsJuru River Valley (Peru and Brazil) 8. Juru River Valley (Peru and Brazil)Social conditions 9. Juru River Valley (Peru and Brazil)Environmental conditions. I. Title.

F 2519.1. A 27 C 36 2005 981.1200498dc22 2004047532

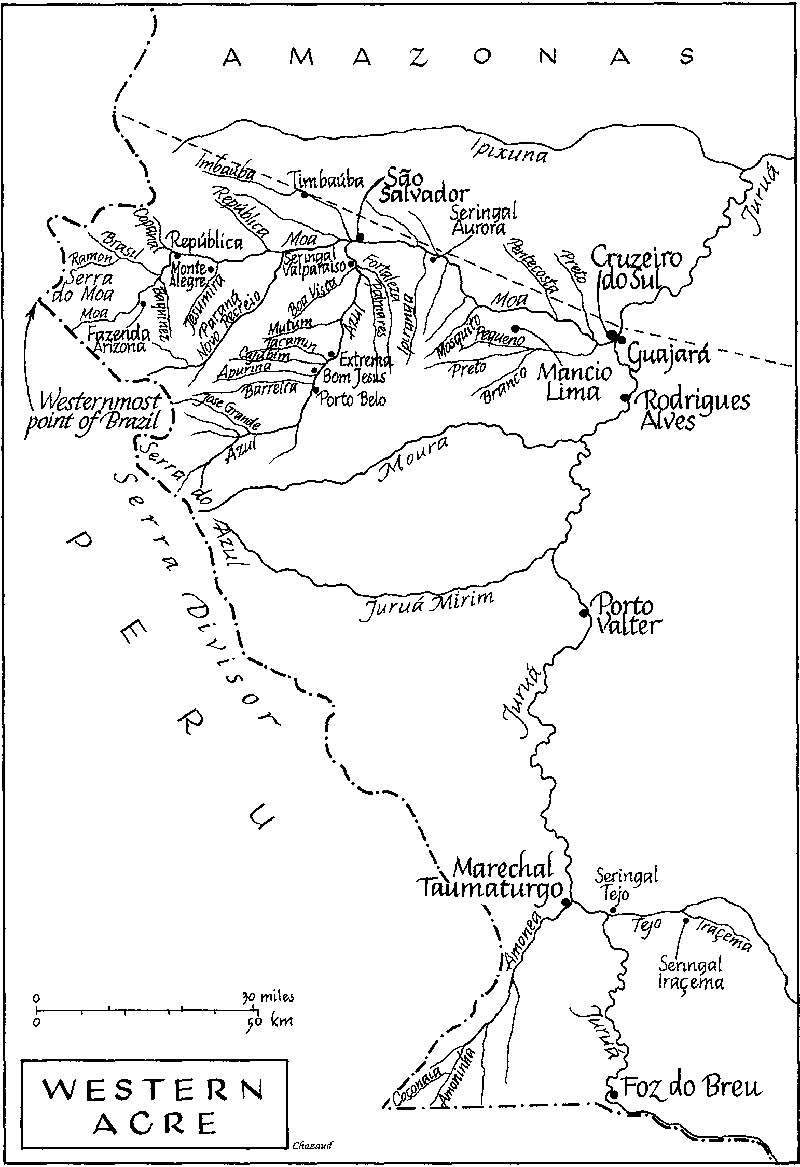

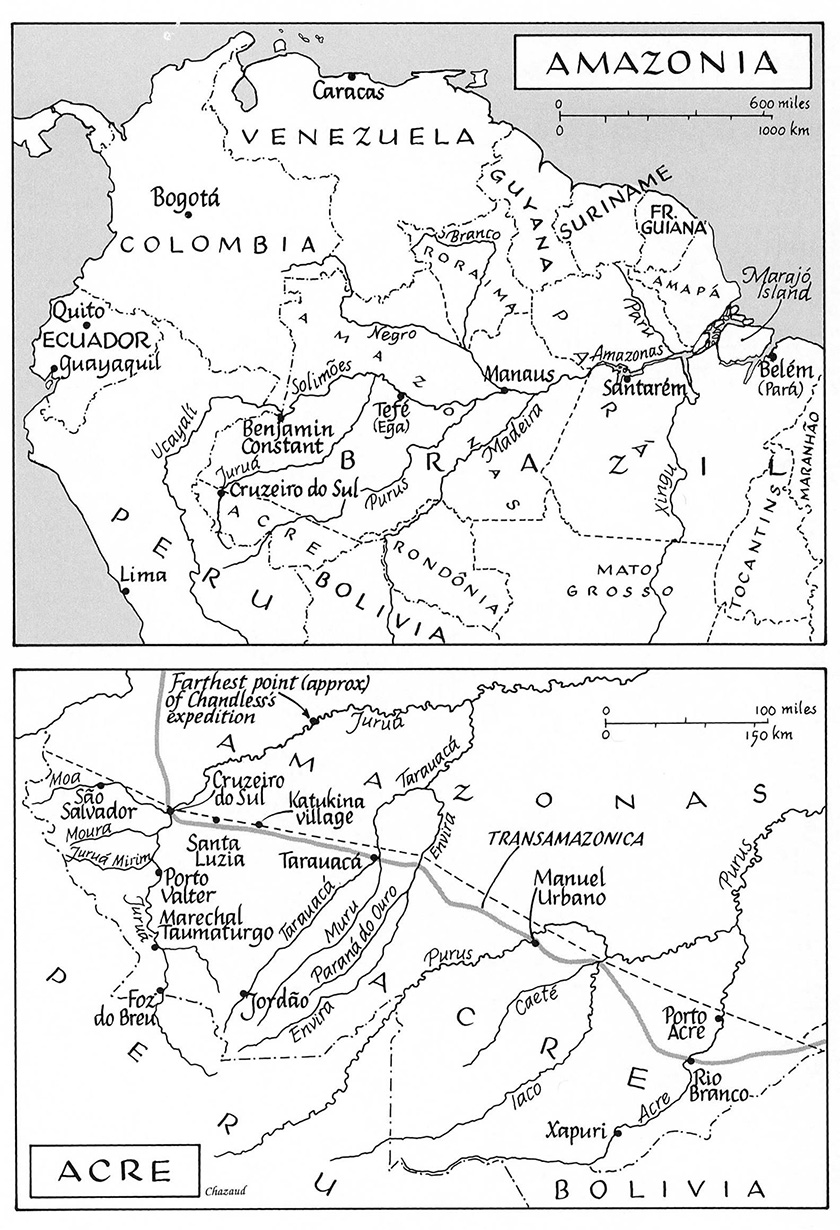

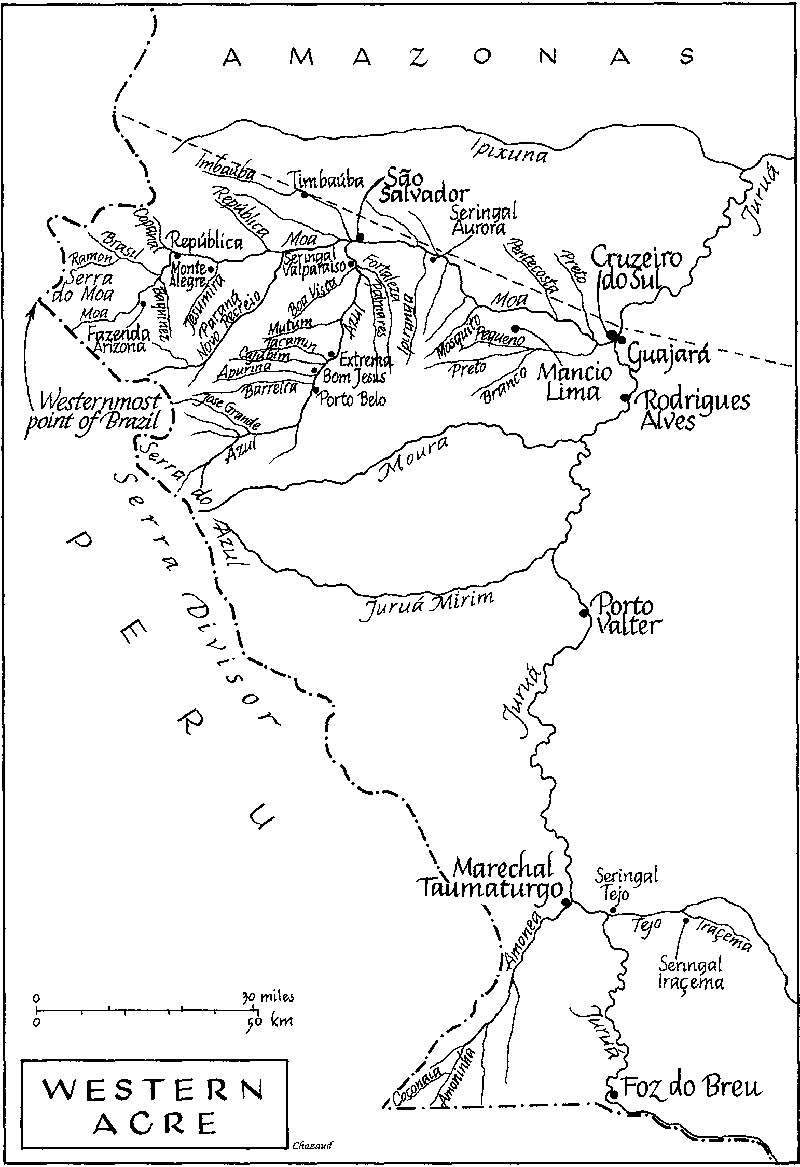

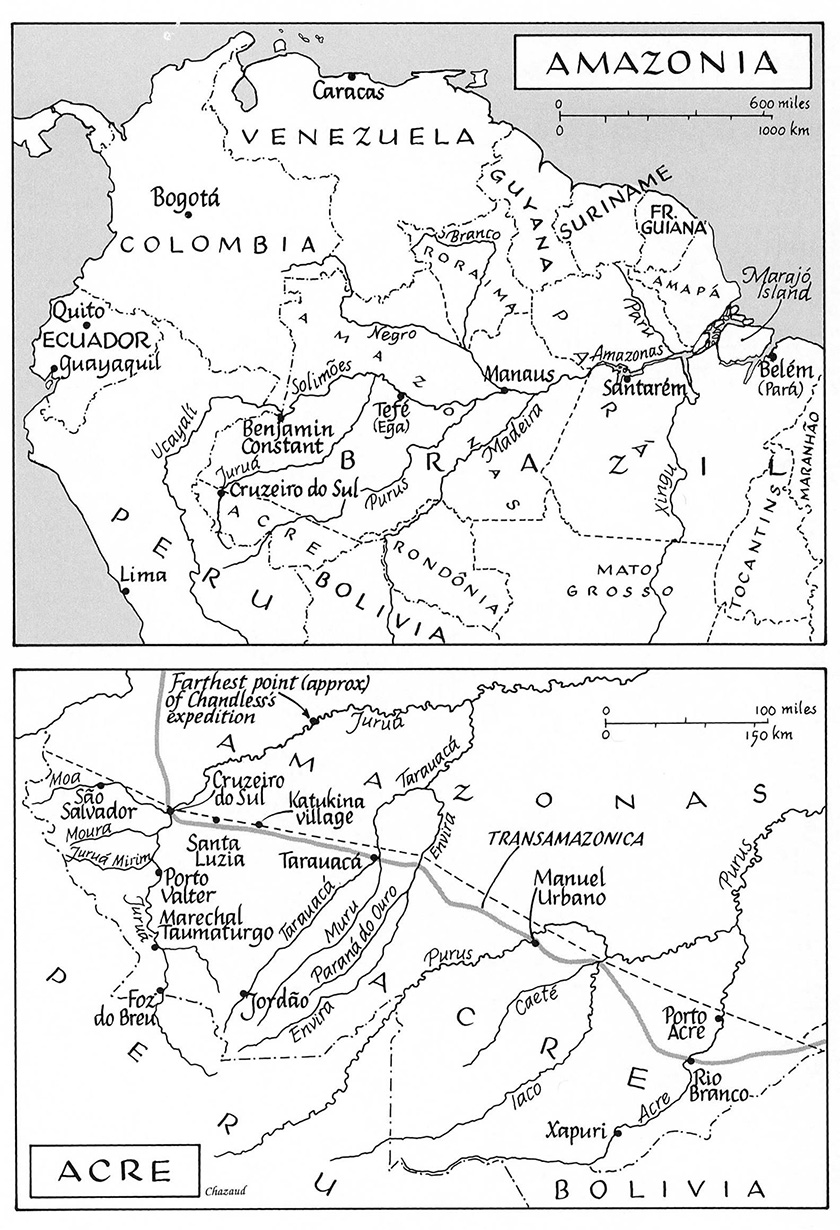

Maps by Jaques Chazaud

e ISBN 978-0-547-52343-9

v2.0421

FOR ORIA

Prologue

The Odyssey

The reality of yesterday becomes a fable

... and one forgets it.

Paul Gauguin

T HIS IS A STORY from the edge of the human presence on our planet, the far western Amazon River Valley, where the forest envelops the horizon and the sky vaults in indifference to our small ways. It is a tale of men and women on a frontier so vast that they seem eclipsed by it. It is the story of their survival and their despairand sometimes their triumph. It is a record of scientists who seek understanding of the natural world and of Native Americans who are losing that world, as their age-old cultureand their cosmosdisintegrates.

For thirty years I have conducted ecological studies in the Brazilian Amazon, in particular around the remote headwaters of the Rio Juru, in the state of Acre, near the Peruvian border. In the course of my journeys there, I have become friends withindeed, part of the extended family ofthe pioneers along the rivers and highways. A wanderer from another continent, I have shared their lives and for a moment was captivated.

I lived among four cultures: the recently arrived colonists from Brazils densely populated east who have settled along the Transamazon Highway; the Caboclos, people of mixed heritage who are masters at making a living along the rivers in this intractable land; the local Native Americans; and the university-trained scholars of the Western empirical scientific tradition.

The colonists settle along the moth-eaten edge of the highwaythe Transamazonicagrowing manioc and coffee and raising a few pigs and chickens in the sandy soils. Some bring the inappropriate farming technologies of Brazils arid east to the tropical rainforest; or, worse, some are city folk with no understanding of farming or the soil. The colonists inevitably fail; the forest succumbs to ephemeral small fires; its fertility is transient.

The Caboclos are fiercely defensive of their lonely environment. Of African, European, even Middle Eastern descentthe vestiges of past diasporasthey are mostly Native American. They all speak Portuguese now. Although most have lost their native languages, they have not necessarily lost all their native skills. They know how to eke out a living in the river and forest. Still, they are not masters of their environment. They are seduced by the forces of commerce, especially by rubber-tapping and cattle-ranching.

The Native Americans, who once understood every nuance of this forest and had a name for every one of its species, have become dislocated and confused, coveting Western ways but unable to grasp them. In a generation many will become Caboclos themselves, but in the quantum jump from Native American to Caboclo they will lose their traditions, their culture, and their very language.

Each family along the rivers has its own tale, often tragic, sometimes heroic. The best interests of the different groups are often in conflict in a land where there is no law, a land neglected by an indifferent government hundreds of miles away. As in the North American West of more than a century and a half ago, conflicts in western Acre today are settled by gunfights and knives; feuds endure for generations.

I came to the River for scienceto explore one of the great and enduring conundrums of nature: how can so many species coexist in such a small patch of this earthly orb? My colleagues and I try to decipher how ecosystems evolve and are maintained. I suppose, in retrospect, that my particular discipline, botany, was irrelevant. I could just as easily have been an entomologist or an ichthyologist. In any case, this lonely terrain would have seduced me into returning again and again. For me, what was important was to bear witness to this place that is like no other, to be a player in the game of science, and to have a dalliance with knowingaware all the while that the paradigms of today will be supplanted by better ideas tomorrow.

How privileged I was to experience this place at this moment in history. Had I made this journey 150 years ago, the vistas and ways of life would have been the same, although my tale would have had more danger. As I do today, I would have reveled in the dumbfounding diversity of life forms. Unlike today, however, then I could have done little more than pose questions.

One might imagine that its a simple goal to understand the way things are assembled on this planet, the rules of order. Yet the measurement of patterns of species abundance and rarityand the slow realization that this diversity was generated not by a benign and constant environment but by disturbance and inconstancyhas been one of the great intellectual quests of our time. How many species can evolve in a small space and be held there? What are those species? Can we ever count them all, describe them? Are they all variations on a limited number of themes, or are they a richly diverse mlange? Why are there any rare species at all? Why havent the most successful species pushed aside the others?

The field work necessary to answer these questions is laborious: every tree and shrub on each small plot must be collected, identified, and mapped. The task is all the more difficult because many of the species in the area I study are new to science, or have been described only in an arcane monograph in a specialized library. I now have data from a total of 18 hectares. A hectare is an area of only 100 by 100 meters, and 18 hectares is just a mote in the vast Amazon Valley. But that small area seems a universe to me. Its diversity is stunning: more than 20,000 individual trees belonging to about 2,000 speciesthree times as many tree species as there are in all of North America. And each tree is an ecosystem unto itself, bearing fungi, lichens, mosses, ferns, aerophytes, orchids, lianas, reptiles, mammals, birds, spiders, scorpions, centipedes, millipedes, mites, and uncountable legions of insects. The number of insect species aloneespecially of beetlesmay exceed the combined total of all the other species of plants and animals in the forest.

From repeated observation and from the patient teaching of the Native Americans and the Caboclos, I have learned to regard each tree on my study sites as an individual: I know its indigenous name, the lore that surrounds it, the medicines that can be made from it, its uses for food or fiber, and myriad other arcane items of its natural history. I know its hitchhikers, the traplining bees that are its pollinators, the bats that disperse its seeds, its parasites, and the lianas that steal its light. I know how the sap smells and feels; how the ocelots have raked its bark and scent-marked it with their urine. I know the generations of pacas that live under its flying buttresses, the army ants that bivouac every few years in its hollow trunk, the tinamou that forlornly flutes from its highest bough. Ive observed its seasons of poverty, when the land is unyielding and sparse, and of productivity, when the red-footed tortoises and white-lipped peccaries eat its fruits. The story of each tree is a story of seasons of birth and death, a story as old as Earth herself.