For Jean, Karen, and Tatiana

First Mariner Books edition 2002

Copyright 1992 by David G. Campbell

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Campbell, David G.

The crystal desert : summers in Antarctica / David G. Campbell,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-395-58969-x ISBN 0-618-21921-8 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-618-21921-6 (pbk.)

1. Natural historyAntarctic regions. 2. SummerAntarctic regions. 3. Campbell, David G.JourneysAntarctic regions. 4. Antarctic regionsDescription and travel. I. Title.

QH 84.2. C 36 1992 92-10583

508.98'9dc20 CIP

e ISBN 978-0-547-52761-1

v2.0421

Acknowledgments

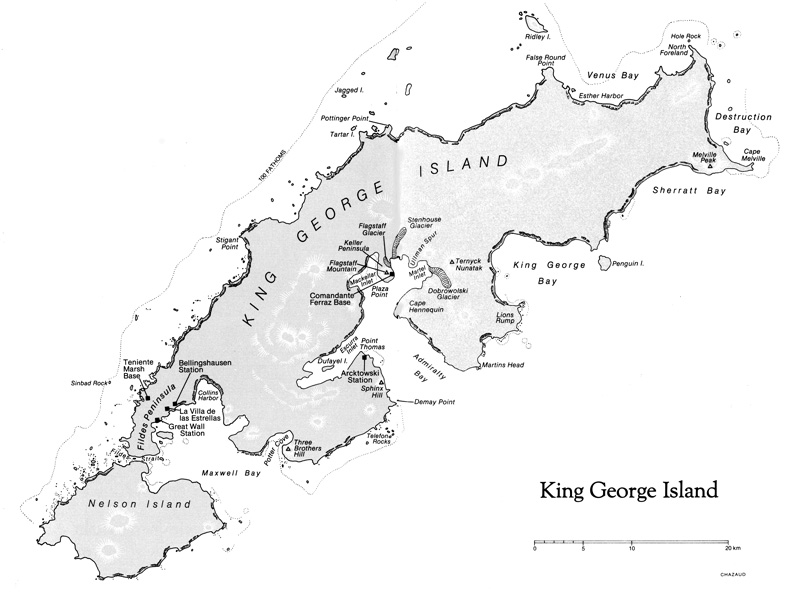

No human can survive alone in the Antarctic, and ones companions in that hostile continent become lifelong friends. I am deeply indebted to Dr. Renato George Ferreira Garcia for inviting me to conduct research at Comandante Ferraz, the Brazilian Antarctic station, for showing me the ropes, and for a fruitful scientific collaboration,. which continues today. I would also like to thank Captain Antonio Jos Gomez Queiroz, Dr. Alexandre de Azavedo Dutra, Dr. Mirian Maria Ferreira Garcia, Dr. Edson Rodrigues, Dr. Claude de Broyer, Gautier Chapelle, Dr. Johann-Wolfgang Wgele, Dr. Hans Gerd Mers, Dr. Phan Van Ngan, Helena Guiro P. P. Coelho, and zero Izidorio Tardin.

I am grateful to Pat Wilcoxon, University of Chicago Libraries, for access to that wonderful collection. I thank G. Douglas, Librarian of the Linnaean Society of London; and William Mills, Librarian, and Robert Headland, Archivist, of the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, for providing records of the early exploration of the Antarctic Peninsula.

For making many helpful comments as to content and style of the manuscript, I thank Dr. Diane Ackerman, Charles Bassett, Lizzie Grossman, Dr. Charles Swithinbank, Dr. Jere Lipps, Dr. Susan Trivelpiece and, especially, Harry Foster and Peg Anderson, editors at Houghton Mifflin.

Prologue: Admiralty Bay

The summers flower is to the summer sweet,

Though to itself it only live and die.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

I SPENT THREE SUMMERS in Antarctica, in places beyond the horizon of most of the rest of my species. The journeys all took place during that single long day that begins in October and ends in March. Sometimes, in the sere, glaciated interior of the continent, Antarctica seemed to be a prebiotic place, as the world must have looked before the broth of life bubbled and popped into whales and tropical forestsand humans. I was as lonely as an astronaut walking on the moon. But at other times, during the short, erotic summer along the ocean margins of the continent, Antarctica seemed to be a celebration of everything living, of unchecked DNA in all its procreative frenzy, transmuting sunlight and minerals into life itself, hatching, squabbling, swimming, and soaring on the sea wind.

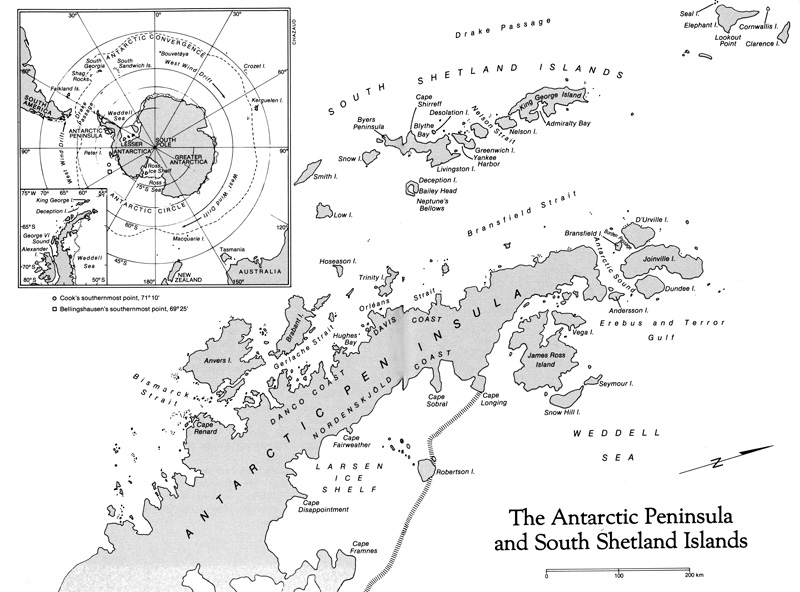

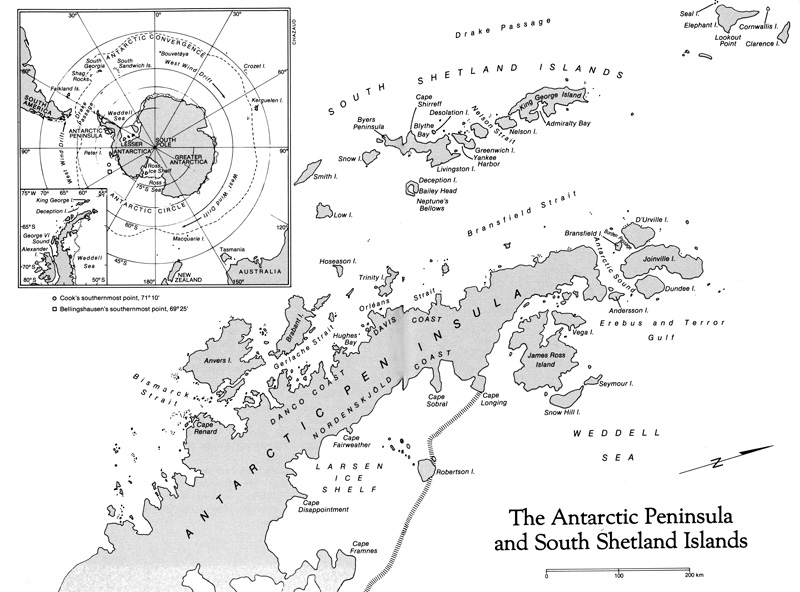

My journeys were principally to the Antarctic Peninsula, a spine of rock and ice at the bottom of the Western Hemisphere that rambles north toward South America from the glacial fastness of the southern continent and then bends eastward, as if submitting to the prevailing westerly winds and currents of the Drake Passage. This is the maritime Antarctic, where the ex It rains frequently during the summer, and once, in late January, I watched the thermometer climb to 9 centigrade. The rest of the continent, ice-fast and arid, is a true desert and is mostly lifeless.

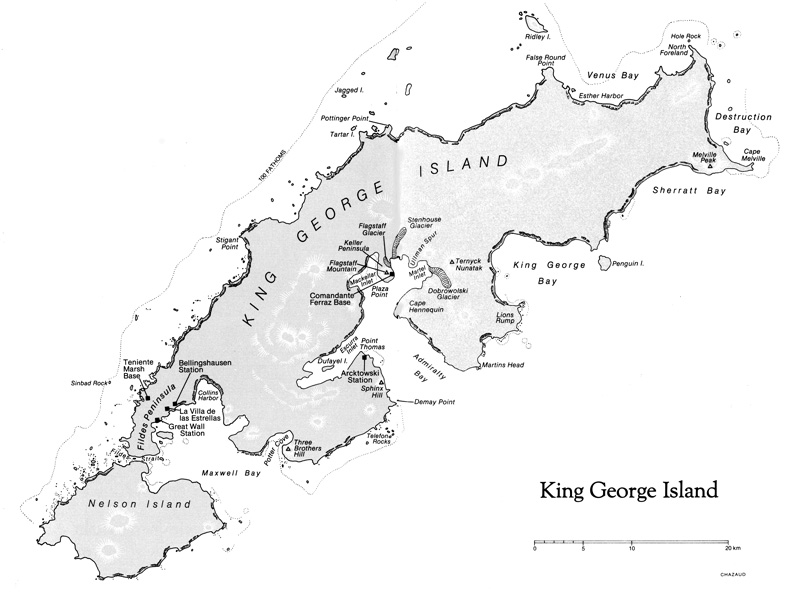

Northwest of the peninsula are the South Shetlands, an ocean-sculpted arc of islands, some with active volcanoes, that reminded the first homesick and frightened Scottish sealers of those treeless, windblown islands of the North Sea. The sealers named the new islands Clarence, Elephant, King George, Nelson, Greenwich, Livingston, and Snow, after various monarchs, captains, mammals, meteorological events, and hometowns. Set off from the archipelago is aptly named Deception Island, an active volcano with a secret caldera where ash-blackened snow mimics rock. These islands of ice and black basalt, now and then tinged russet or blue by oozings of iron or copper, rise over 600 meters. Their hearts are locked under deep glaciers, a crystal desert forever frozen in terms of our short life spans, but transient in their own time scale. Sometimes one sees only the cloud-marbled glacial fields, high in the sun above hidden mountain slopes and sea fog, Elysian plains that seem as insubstantial as vapor. The interiors of the glaciers, glimpsed through crevasses, are neon blue. Sliding imperceptibly on their bellies, the glaciers carve their own valleys through the rock, and when they pass over rough terrain they have the appearance of frozen rapids, which is in fact what they are, cascading at the rate of a centimeter a day. Sudden cold gusts, known as katabatic winds, tumble down their icefalls to the shore; sometimes the coast snaps from tranquility to tempest in just a few minutes. Just as quickly the glacial winds abate, and there is calm. Where they reach the sea, the glaciers give birth to litters of icebergs, which usually travel a short distance and, at the next low tide, run aground on hidden banks. Most of the ice-free land is close to shore, snuggled near the edge of the warm sea in places that are buffeted by both sea wind and land wind, where rain changes to snow and back. There is no plant taller than a lichen here, no animal larger than a midgebiological haiku. But on protected slopes, where the snow melts on warm summer days and glacial meltwater nourishes the soil, lichens and mosses dust the hills a pale gray-green, and the islands take on a tenuous verdancy.

The Pacific and Atlantic oceans meet at the South Shetland Islands. Indeed, all of the worlds oceans mix in the Southern Ocean, the circumpolar sea that so absolutely isolates Antarctica from the other continents. Only a few small islands fleck this globe-girdling sea, and the westerly storms that orbit the Earth at these latitudes, unimpeded by land masses and always sucking energy from the sea, develop the anger of hurricanes. These zones are the roaring forties and screaming fifties, which have commanded the respect and fear of sailors since the time of Francis Drake. Today satellite photographs show these low-pressure zones, spiraling clockwise, regularly spaced, separated by several hundred kilometers of calm seaa flowered anklet on the planet Earth. But the Southern Ocean is a manic sea, and between the tempests there is tranquility and light. To the land-bound on the South Shetland Islands, the distance between cyclones is measured in time, three to five days apart.

If the bright ice and dark rock are the canvas of these desert islands, then light is the medium, and the Southern Ocean, ever fickle, often angry, is the artist. She swathes the islands in mist, or snow, or clarid sea-light, depending on her moods. Sometimes the sea rages for days, and you can lean against the wind, rubbery and firm. The wind lifts the round pebbles from the beach and flings them like weapons at hapless beachcombers. The cyclonic winds march around the compass, so at one moment they will herd the icebergs against the shore in a groaning cluster, and a few hours later waft them out to sea like feathers on a pond. At other times there will be a clammy calm, a disquieting purple grayness that smothers light and sound, punctuated only by the distant, muffled crack of a calving glacier. The days one anticipates are the tranquil ones that break the long captivity of cabin fever, when the sky is a transparent blue, and the deep, clear sea scintillates with shafts of sunlight.