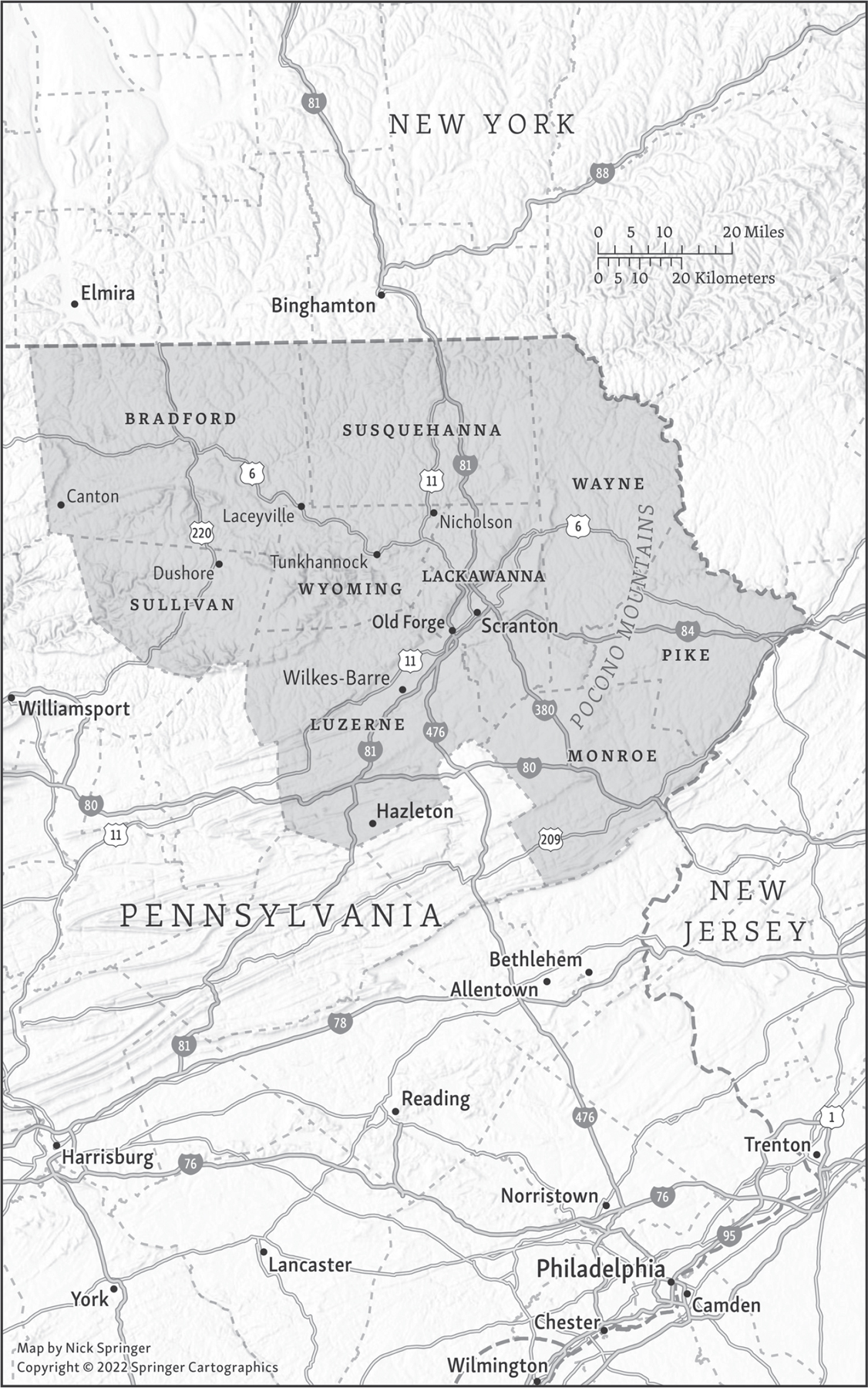

J anuary had been a terrific month inside Cusumanos, an Italian restaurant in Old Forge, Pennsylvania, a town of eight thousand a few miles south of Scranton. The dining room was packed every weekend, despite temperatures that sometimes dipped down into the single digits. So, too, was a downstairs bar area called the Cellar. TJ Cusumano, a thickly built thirty-four-year-old, had started cooking when he was in grade school. His wife, Nina, two years his junior, had been working in restaurants since the age of sixteen. There had been moments since they first opened Cusumanos in 2013 when the couple regretted ever getting into the restaurant business. The food was delicious, and they had the accolades to prove it. But the couple sometimes went months without drawing a salary. They lived off the tips Nina earned serving the food.

By January of 2020, though, they were drawing crowds even on Wednesdays and Thursdays. The good times continued into February. Valentines Day that year fell on a Friday. The restaurant had probably its best Friday night in its seven-plus years of operation, making for a blockbuster three-day weekend that ranked among their top grossing since they first opened.

We felt like we were really making it, TJ said.

The crowds thinned in the second half of the month, and the Cusumanos told themselves that a drop-off was inevitable. Yet February turned into March, and one or the other of them glanced at the binder they left open by the phone for writing down reservations. There were few names listed even on a Friday or Saturday night. Just the winter blues, the Cusumanos reassured each other. They chalked up the slowdown to the cyclical nature of the restaurant business and a population tired of trekking outside at the end of a long winter. On some nights, they seemed more like weather forecasters than restaurateurs. Low of twenty-five tonight, one said to the other to explain a dining room barely half-full on the last Saturday night of February. Another night it was freezing rain turning to ice.

Reservations remained down even as the temperature outside warmed up in early March. TJ kept up with current events and had read about this new strain of coronavirus spreading around the globe. At that point, though, the virus had barely reached the shores of the US. Even then, only a few cases had been reported on either coastfar from their modest-sized burgh. Neither mentioned the pending pandemic as a possible explanation for the steep drop-off in reservations.

The date stamps on the food the restaurant was getting from their suppliers were another early sign of the calamity about to hit Old Forge and the rest of the world. Cusumanos was one of a half-dozen Italian eateries on Main Street in Old Forge, an old coal miners town. Phyllis Mischello, the owner-chef of Anthonys down the street, phoned. So, too, did Russell Rinaldi at Cafe Rinaldi next door and other restaurant owners in town. All of them asked the same question: Were his purveyors sending him older product? TJ noticed the difference in the fish. The catch that typically had been caught within forty-eight hours was now several days out of the water.

Im starting to make the correlation, TJ said. He began to see the impact of the coronavirus on their business.

We stopped spending money in any way we could, he said. Ordering less food. Cutting down on our alcohol purchase. Cutting peoples hours.

On the second Friday of MarchFriday the thirteenthtemperatures hit a high of sixty-four. The crowd that night was still sparse. That Saturday Scranton would have held its annual St. Patricks Day parade. In normal times, that would mean an overflow crowd and fat bar bills both in the main dining room and downstairs in the Cellar. This place would have been a total zoo, Nina said. But Scranton canceled its parade. Bob Mulkerin was behind the bar in the Cellar that night. Mulkerin was a lifelong Old Forger whod started bartending on Saturday nights in 2017, after serving a single term as town mayor. (I care about my kids was his rationale both for running and deciding not to run for reelection.) Normally, Mulkerin pocketed a couple of hundred dollars in tips on a busy Saturday night. He was lucky if he made $50 that night. A small surprise party was up in the air until a few hours before the guests slated to arrive. They went ahead with the celebration, but the only other people there that night were the battered regulars who parked themselves on the same bar stools night after night. In a room that in normal times practically vibrated with good cheer, the mood was more that of a wake.

On Sunday, the mayor of Philadelphia, two hours to the south, suspended indoor dining. The governor put the same restrictions on restaurants in the suburbs surrounding Philadelphia and also in Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh. TJ recalled the night as a last hurrah, as if people sought one more night out before the inevitable. It was kind of a good Sunday, which kind of shocked us, TJ said. At the end of the shift, he sat with Jessica Barletta, a waitress who had been with him and Nina since they first opened their doors. She was herself a small business operator with her own dance studio in Scranton.

TJs like, Im pretty sure were not going to be open this Wednesday, Barletta recalled. (Cusumanos is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays.) I was like, Yeah. Pennsylvanias governor, Tom Wolf, made it official that Monday. Restaurants could still offer takeout and delivery. But Wolf signed an order shutting down indoor dining everywhere in the state.

TJs first hours in lockdown were spent largely on his phone, texting or talking with the restaurants two dozen employees. The servers and bartenders tended to have other sources of income but not his kitchen staff, who needed a paycheck to pay the rent and buy food. That would be his first hard decision: Whom could he afford to keep, if anyone, and whom would he lay off?

TJ tried not to think about the timing. A landmark moment for any business is establishing a retirement program for its employees. Finally, he and Nina were making enough to start a 401(k) for themselves and several longtime employees. They were only a couple of weeks from finalizing a small benefits package that matched an employees contributions to a retirement fund when the governor issued his shutdown order. The 401(k) would be added to the list of things that needed to be put on hold for who knew how long.

We had been very blessed, TJ said. Coming into our seventh year, we were really hitting our stride. In the prior fifty-two weeks, he figured that they had experienced two or three slow weeks. Yet suddenly he was looking at an indefinite closure.

Things had really been going great, he said.

And like that, they werent.

* * *

Fifty minutes south of Cusumanos on the interstate lies Hazleton, another old coal mining town. Both Hazleton and Old Forge date back two centuries to when northeastern Pennsylvanias coal and iron ore helped power the Industrial Revolution. Yet the modern-day version of each stands as a polar opposite of the other. What distinguishes Old Forge is how little the town has changed over the years. Old Forge was Italian one hundred years ago just as it is Italian today, even as it has the Polish Alps, a hilly neighborhood where those of Polish ancestry first settled, and a token Irish pub. People commute to jobs in Scranton or work in town. There are warehouse jobs at a wholesale beer and soda distributor that ranks as one of Pennsylvanias biggest and more to be found at the sprawling lumber and kitchen supply warehouse just off the main road into town. Many find work inside one of the Italian eateries that for generations have drawn people to Old Forge.