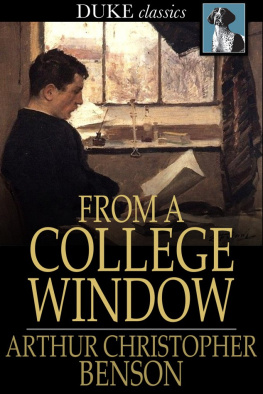

Arthur Christopher Benson - From a College Window

Here you can read online Arthur Christopher Benson - From a College Window full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Duke Classics, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:From a College Window

- Author:

- Publisher:Duke Classics

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

From a College Window: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "From a College Window" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Throughout his life, poet and essayist Arthur Christopher Benson also worked as an educator and school administrator. This collection of essays presents Bensons views on topics ranging from art to the aging process, filtered through the lens of someone who is actively engaged in the difficult but rewarding work of educating a nations youth.

From a College Window — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "From a College Window" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published in 1906

ISBN 978-1-62013-924-0

Duke Classics

2014 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Mens cujusque is est quisque

Twelve of the essays included in this volume appeared in the CornhillMagazine. My best thanks are due to the proprietor and editor of theCornhill Magazine for kind permission and encouragement to reprintthese. I have added six further papers, dealing with kindred subjects.

A. C. B.

I have lately come to perceive that the one thing which gives value toany piece of art, whether it be book, or picture, or music, is thatsubtle and evasive thing which is called personality. No amount oflabour, of zest, even of accomplishment, can make up for the absence ofthis quality. It must be an almost wholly instinctive thing, I believe.Of course, the mere presence of personality in a work of art is notsufficient, because the personality revealed may be lacking in charm;and charm, again, is an instinctive thing. No artist can set out tocapture charm; he will toil all the night and take nothing; but whatevery artist can and must aim at, is to have a perfectly sincere pointof view. He must take his chance as to whether his point of view is anattractive one; but sincerity is the one indispensable thing. It isuseless to take opinions on trust, to retail them, to adopt them; theymust be formed, created, truly felt. The work of a sincere artist isalmost certain to have some value; the work of an insincere artist isof its very nature worthless.

I mean to try, in the pages that follow, to be as sincere as I can. Itis not an easy task, though it may seem so; for it means a certaindisentangling of the things that one has perceived and felt for oneselffrom the prejudices and preferences that have been inherited, or stucklike burrs upon the soul by education and circumstance.

It may be asked why I should thus obtrude my point of view in print;why I should not keep my precious experience to myself; what the valueof it is to other people. Well, the answer to that is that it helps oursense of balance and proportion to know how other people are looking atlife, what they expect from it, what they find in it, and what they donot find. I have myself an intense curiosity about other people's pointof view, what they do when they are alone, and what they think about.Edward FitzGerald said that he wished we had more biographies ofobscure persons. How often have I myself wished to ask simple, silent,deferential people, such as station-masters, butlers, gardeners, whatthey make of it all! Yet one cannot do it, and even if one could, tento one they would not or could not tell you. But here is going to be asedate confession. I am going to take the world into my confidence, andsay, if I can, what I think and feel about the little bit of experiencewhich I call my life, which seems to me such a strange and often sobewildering a thing.

Let me speak, then, plainly of what that life has been, and tell whatmy point of view is. I was brought up on ordinary English lines. Myfather, in a busy life, held a series of what may be called highofficial positions. He was an idealist, who, owing to a vigorous powerof practical organization and a mastery of detail, was essentially aman of affairs. Yet he contrived to be a student too. Thus, owing tothe fact that he often shifted his headquarters, I have seen a gooddeal of general society in several parts of England. Moreover, I wasbrought up in a distinctly intellectual atmosphere.

I was at a big public school, and gained a scholarship at theUniversity. I was a moderate scholar and a competent athlete; but Iwill add that I had always a strong literary bent. I took in youngerdays little interest in history or polities, and tended rather to livean inner life in the region of friendship and the artistic emotions. IfI had been possessed of private means, I should, no doubt, have becomea full-fledged dilettante. But that doubtful privilege was denied me,and for a good many years I lived a busy and fairly successful life asa master at a big public school. I will not dwell upon this, but I willsay that I gained a great interest in the science of education, andacquired profound misgivings as to the nature of the intellectualprocess known by the name of secondary education. More and more I beganto perceive that it is conducted on diffuse, detailed, unbusiness-likelines. I tried my best, as far as it was consistent with loyalty to anestablished system, to correct the faulty bias. But it was with aprofound relief that I found myself suddenly provided with a literarytask of deep interest, and enabled to quit my scholastic labours. Atthe same time, I am deeply grateful for the practical experience I wasenabled to gain, and even more for the many true and pleasantfriendships with colleagues, parents, and boys that I was allowed toform.

What a waste of mental energy it is to be careful and troubled aboutone's path in life! Quite unexpectedly, at this juncture, came myelection to a college Fellowship, giving me the one life that I hadalways eagerly desired, and the possibility of which had always seemedclosed to me.

I became then a member of a small and definite society, with a fewprescribed duties, just enough, so to speak, to form a hem to my lifeof comparative leisure. I had acquired and kept, all through my life asa schoolmaster, the habit of continuous literary work; not from a senseof duty, but simply from instinctive pleasure. I found myself at onceat home in my small and beautiful college, rich with all kinds ofancient and venerable traditions, in buildings of humble and subtlegrace. The little dark-roofed chapel, where I have a stall of my own;the galleried hall, with its armorial glass; the low, book-linedlibrary; the panelled combination-room, with its dim portraits of oldworthies: how sweet a setting for a quiet life! Then, too, I have myown spacious rooms, with a peaceful outlook into a big close, halforchard, half garden, with bird-haunted thickets and immemorial trees,bounded by a slow river.

And then, to teach me how "to borrow life and not grow old," the happytide of fresh and vigorous life all about me, brisk, confident,cheerful young men, friendly, sensible, amenable, at that pleasant timewhen the world begins to open its rich pages of experience, undimmed atpresent by anxiety or care.

My college is one of the smallest in the University. Last night in HallI sate next a distinguished man, who is, moreover, very accessible andpleasant. He unfolded to me his desires for the University. He wouldlike to amalgamate all the small colleges into groups, so as to haveabout half-a-dozen colleges in all. He said, and evidently thought,that little colleges are woefully circumscribed and petty places; thatmost of the better men go to the two or three leading colleges, whilethe little establishments are like small backwaters out of the mainstream. They elect, he said, their own men to Fellowships; they resistimprovements; much money is wasted in management, and the whole thingis minute and feeble. I am afraid it is true in a way; but, on theother hand, I think that a large college has its defects too. There isno real college spirit there; it is very nice for two or three sets.But the different schools which supply a big college form each its ownset there; and if a man goes there from a leading public school, hefalls into his respective set, lives under the traditions and in thegossip of his old school, and gets to know hardly any one from otherschools. Then the men who come up from smaller places just form smallinferior sets of their own, and really get very little good out of theplace. Big colleges keep up their prestige because the best men tend togo to them; but I think they do very little for the ordinary men whohave fewer social advantages to start with.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «From a College Window»

Look at similar books to From a College Window. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book From a College Window and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Robert Hugh Benson [Benson - Robert Hugh Benson Collection [11 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/139831/thumbs/robert-hugh-benson-benson-robert-hugh-benson.jpg)