2002, 2010 by the Smithsonian Institution.

All rights reserved

A different version of appeared as What Should Women (and Men) Want? Advertising Air-Conditioning in the Fifties in the Columbia Journal of American Studies 3 (Summer/Fall 1998).

Editor: Ruth W. Spiegel

Designer: Janice Wheeler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

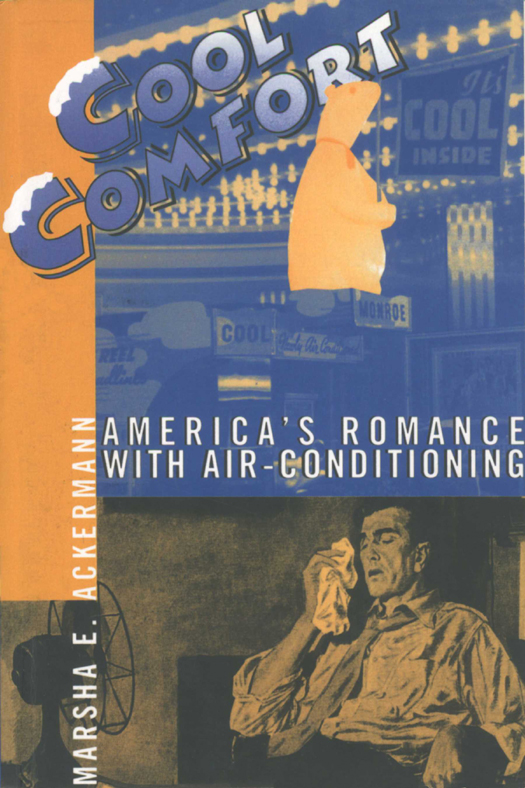

Ackermann, Marsha E.

Cool comfort: Americas romance with air-conditioning / Marsha E. Ackermann.

p. cm.

1. Air-conditioning I. Title

TH7687.A25 2002

697.930973dc21

2001049023

A paperback reissue (eISBN: 978-1-58834-401-4)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available.

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the work as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

v3.1_r1

Acknowledgments

I have been a writer all my life but this is my first book. I want to thank the University of Michigans Program in American Culture, especially Professor David Hollinger, now at the University of California Berkeley, for taking a chance in 1988 on this rather senior graduate student. Professors S. Cushing Strout and Joel Silbey inspired me long ago during my undergraduate years at Cornell University; their support, along with that of political scientist Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution, helped me realize my midlife dream of a Ph.D.

The members of my dissertation committee encouraged my work in ways that belie conventional notions of academia. Chair Martin S. Pernick was consistently available for consultation, imparted his nuanced knowledge of medical history, and entrusted me with library privileges. David M. Scobey shared his lucid insights into the social geography of nineteenth-century New York City. Laurence Goldstein responded swiftly and in detail to both the writing and the content of each emerging chapter. Joel Howell graciously stepped in at a late stage and enriched the final work. Kristin Hass, then a fellow graduate student, materially assisted with her enthusiasm and astute suggestions. At Michigan State University, American Thought & Language chair Douglas Noverr gave me a chance to teach and alerted me to the Syracuse Carrier Domes odd deficiency.

History is impossible without libraries, archives, and those who make them accessible. During the two extremely hot July weeks I spent with Ellsworth Huntington and Charlie Winslow in Yale Universitys magnificent Sterling Library, I was grateful not only for the skilled staff but for the phalanx of huge fans that kept the reading room balmy, while the climate-control system, hidden in the nether regions, preserved these irreplaceable records.

Thanks are also due to Cornell Universitys Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections at the Kroch Library, home to the Carrier Corporation Records. The librarys willingness to make most of the collection available on microfilm significantly eased the time and expense of my research. The New York Public Librarys New York Worlds Fair archives and the New-York Historical Societys collection of diaries were also helpful. At New Yorks East Side Tenement Museum, Vin Lenza let me set up my laptop in the staff lunchroom.

Long before I proposed this book to the Smithsonian Institution Press, the Smithsonian Archives Center at the National Museum of American History had already proved to be invaluable. Special thanks to Jon Zachman, who located pertinent materials while he was still processing the Edward J. Orth Memorial Archives of the Worlds Fair. Charles F. McGovern and William E. Worthington offered insights into the history of technology.

My research would have been impossible without the spectacularly rich and diverse collection of the University of Michigan library system. As I prowled the stacks of a dozen separate libraries, piecing together the greatest story never told, I was grateful to have such a wealth of material at hand or just an Interlibrary Loan away.

Many individuals kindly spent time answering my questions in person, by telephone, or e-mail. Joel A. Wasserman of the John B. Pierce Laboratory in New Haven explained its history and ongoing work during our July 1993 meeting there. Douglas Gomery of the University of Marylands College of Journalism shared his insights into movie theater air conditioning over dinner in Washington, D.C. John M. Anderson of the GE Hall of History, now part of the Schenectady Museum, provided information on General Electrics air-conditioning business. Arlene Mathison at Dayton Hudsons (now Target Corporation) Research Center in Minneapolis located historical information about Detroits J. L. Hudson department store.

At a publishers booth in the over-air-conditioned basement of the Washington Hilton, where the Organization of American Historians gathered in 1995, I made a very fortunate cold call on Smithsonian Institution Press senior editor Mark G. Hirsch. His enthusiasm, sustained over years, and the astute suggestions and criticisms provided by the two anonymous reviewers he selected, made possible the much-improved version offered herein. Thanks to veteran executive editor Ruth W. Spiegel, a person of unfailing tact, patience, inspiration, and bountiful good sense, the editing process was a wholly gladsome undertaking.

I have not yet met Professor Gail Cooper, but I want to thank her not only for her groundbreaking work on air-conditioning, but also for passing my name along to several editors of relevant reference works. Those exercises in distillation helped this book immensely. An April 1996 Great Lakes American Studies Association symposium on the Cold War gave me a chance to try out some of my ideas on an audience both critical and receptive. My thanks to Professor Russell Reising of the University of Toledo.

Friends and family did not, of course, sit idly by. For clippings both print and electronic, accommodations during research sorties, and much moral and intellectual support, I am grateful to Joan Alexander, Lise Bang-Jensen, Erik Brady and Carol Stevens, Ellen Gardner, Ray and Eleanor Lewis, Susan Metzger, Ruth Metzstein, Saul Metzstein, Tim Murray, Nancy Schwerzler, and especially Charles J. Sennet, photo wrangler.

My dear aunt, Jenny Metzstein, who suffers heat but not fools gladly, has not only welcomed me into her Manhattan apartment before, during, and after research trips, but actually read my dissertation from cover to cover. My husband, Thomas K. Black III, has enhanced my life even more than my Ph.D. did. And he is teaching me how to fish.

Introduction

T o a surprising extent, wrote medical ecologist Ren Dubos in 1965, modern man has retained unaltered the bodily constitution, physiological responses, and emotional drives which he has inherited from his Paleolithic ancestors. Yet he lives in a mechanized, air-conditioned, and regimented world radically different from the one in which he evolved.

No world is more air-conditioned than the one in which todays American men and women spend their lives. Air-conditioning, defined as mechanical cooling by means of refrigeration, has in just a century transformed the United States. Indoor weather manufactured by air-conditioning equipment haswhether we accept the claims of its promoters or the complaints of its detractorstamed the nations anarchic seasons and imposed uniformity on a climatically diverse continent. It has helped reshape cities, houses, farms, even our bodies, coming closer than any other technology to producing the weatherlessness long envisioned by American utopians who have typically confused technological control with social perfection.