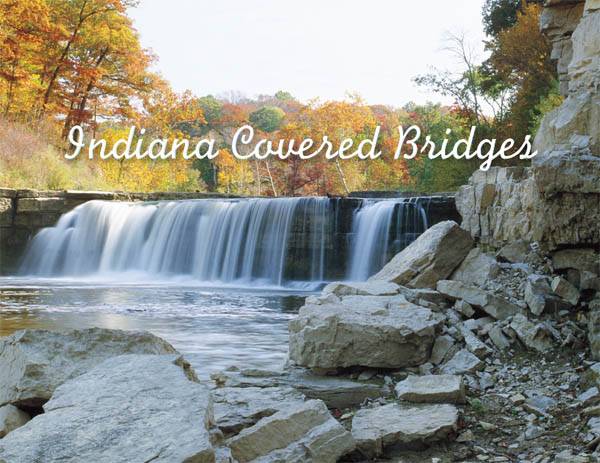

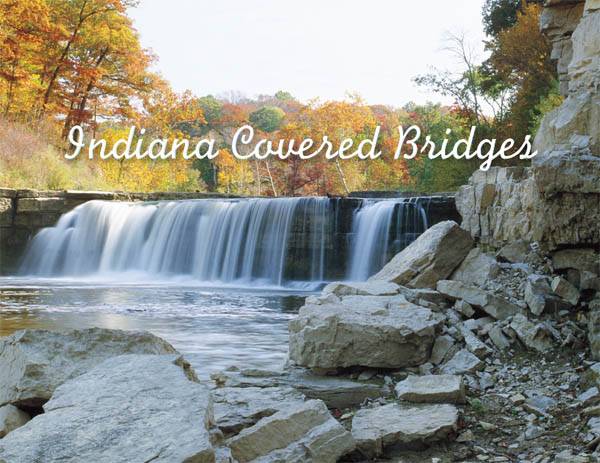

The Cataract Falls cascade into Mill Creek in Owen County.

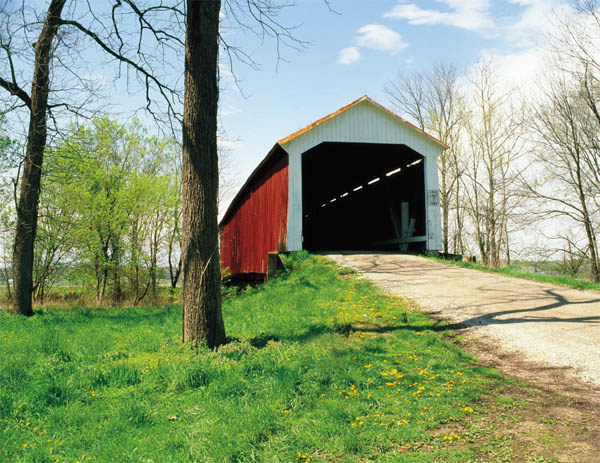

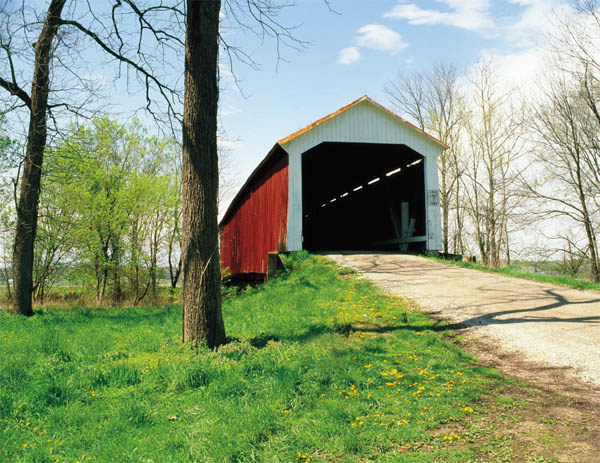

Neet Bridge, built in 1904, crosses Little Raccoon Creek in Parke County.

INDIANA

Covered Bridges

MARSHA WILLIAMSON MOHR

Foreword by

RACHEL BERENSON PERRY

This book is a publication of

QUARRY BOOKS

an imprint of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 474043797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2012 by Marsha Williamson Mohr

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mohr, Marsha Williamson.

Indiana covered bridges / Marsha Williamson Mohr ; foreword by Rachel Berenson Perry.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-253-00800-8 (cl : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-00801-5 (ebook)

1. Covered bridgesIndiana. I. Title.

TG24.16M65 2012

624.21809772dc23

2012010161

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15 14 13 12

Contents

BY RACHEL BERENSON PERRY

Dunbar Bridge, built in 1880, crosses Big Walnut Creek in Putnam County.

FOREWORD

The Allure of the Covered Bridge

RACHEL BERENSON PERRY

THE MEANDERING OHIO AND WABASH RIVERS shape the southern borders of our great state of Indiana, and multiple streams and tributaries crisscross our 92 counties like fine lines of age on a familiar face. From the Kankakee, Yellow, and Eel Rivers in the north; through central Indianas Wildcat Creek, Mississinewa, and the forks of the mighty White River; to Pigeon Creek, the Muskatatuck and Blue Rivers in the south; the waterways have trickled and gushed since before the Northwest Territorys first settlers.

Tell-tale sentries of white-trunked sycamores marking creek banks through meadows and along ravines; dramatic limestone bluffs overlooking the Ohio River; and pastoral brooks that are transformed into raging floodwaters each spring; are all part of our collective consciousness as Hoosiers.

The bridges that cross our plethora of waterways, however, are rarely considered. We drive at high speeds over elevated road surfaces that barely differ from the rest of the highway, often with side barriers blocking our view of the river below. Traveling without hindrance along public thoroughfares seems like a basic entitlement.

Rivers and creeks, however, were formidable impediments that caused lengthy detours and precarious travel conditions in the early 1800s. The neophyte state of Indiana in the 1820s initiated a system of State Roads to connect the larger settlements. With most early settlers arriving from the south, the first road built connected New Albany to Paoli, and later extended west to Vincennes. Within a decade, this expanding road included Bloomington, Greencastle, Crawfordsville, and Lafayette.

As state counties were established, the main concern for elected commissioners became the locations of proposed roads. The first improved roads beginning in 1848, plank roads, consisted of large tree trunks laid approximately fourteen feet apart on each side with smaller trees trimmed and placed adjacently across the trunks. This method of road building, especially useful for traversing swampy areas, was short-lived due to the inevitable rotting and destruction of the wood.

Privately managed companies, called gravel road companies, organized and took over the building and maintenance of the county roads. Each company consisted of land owners along the proposed road, members to be taxed according to the value of their land. The company agreed to maintain the road, including culverts and bridges, and could collect tolls from non-residents. Every male citizen

In the late 1880s, counties started buying out these private road companies, and in a few years all main roads became public property. This did not completely eliminate tolls, however, as fees determined by county commissioners were typically charged for bridge crossings.

Tolls in 1867 to traverse bridges over the Wabash River in Lafayette, for example, were set at twenty-five cents for four-wheeled carriages, wagons, or sleighs pulled by two horses, oxen, or other animals; fifteen cents for conveyances drawn by one animal; ten cents for each horse, ass, or mule with one rider; two cents for a footman, each riderless horse or mule; three cents for each head of cattle; and one cent apiece for every sheep or hog. Also, when the circus was coming to town, it cost a whopping one dollar to get an elephant across and fifty cents for each camel.

An anecdote about covered bridge fees involves Indianas famous poet, James Whitcomb Riley:

It seems that Riley appeared one winters night at an entertainment in Bloomington. Hoping to catch a train at Gosport he hired a buggy and driver to fetch him the 18-odd miles. With every step the vehicles two little western horses broke through the crust of ice, which covered the road, and could only plod along at a walk.

Dawn was breaking when the rig and its weary occupants came in sight of the breakfast smokes of Gosport. Riley puts it: Just as we approached the covered bridge, the driver leaned forward and said, Mr. Riley, can you see what it says on the end of that bridge?

Yes, said I. It says $5 Fine for Driving Through this Bridge Faster than a Walk.

He gave the whip just as the hooves of the horses struck the board floor, and brought it down with a switch on the backs of the animals. The horses that had walked all night suddenly leaped into action. It seemed to me we went through that bridge about ninety miles an hour.

Aha! shouted the driver. Heres where I get my five dollars worth!

What Riley didnt say is that half of the fine typically went to the informer, so if nobody tattled, they likely kept their money.

Although it seems likely that the horses in Rileys story were whipped into a gallop, the reason for requiring horses to walk across bridges was based upon the belief that a team of horses at a trot would coordinate their pace with one another. It was believed this cadence vibration could do damage to the bridge. So, the driver would have to slow his team to a walk to avoid this. Also, a lot of Civil War troops trained on and around the bridges. Their marching could do similar damage so they had to obey the same law.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.