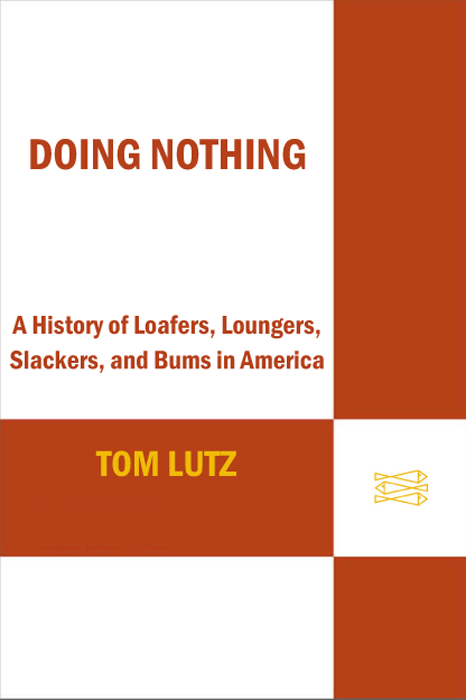

Tom Lutz

Tom LutzDOING NOTHING

Tom Lutz is the author of Crying: The Natural and Cultural History of Tears, which The Washington Post called a tour de force of erudition. His other books include American Nervousness, 1903: An Anecdotal History and Cosmopolitan Vistas: American Regionalism and Literary Value. He lives in Los Angeles.

ALSO BY TOM LUTZ

American Nervousness, 1903: An Anecdotal History

Crying: The Natural and Cultural History of Tears

Cosmopolitan Vistas: American Regionalism and Literary Value

D O I N G N O T H I N G

A HISTORY OF LOAFERS, LOUNGERS, SLACKERS,

AND BUMS IN AMERICA

Tom Lutz

FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX

NEW YORK

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

19 Union Square West, New York 10003

Copyright 2006 by Tom Lutz

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America

Published in 2006 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

First paperback edition, 2007

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Lutz, Tom.

Doing nothing : a history of loafers, loungers, slackers and bums in

America / Tom Lutz. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-86547-650-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-86547-650-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. SlackersUnited StatesHistory. 2. LazinessUnited States

History. I. Title.

BJ1498.L88 2006

174dc22

2005027230

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-86547-737-7

Paperback ISBN-10: 0-86547-737-X

Designed by Debbie Glasserman

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

TO MY WRITING PARTNERS,

CODY AND LAURIE,

AND IN MEMORIAM

KEN CMIEL

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

In which the author confronts his sons lazinessand remembers his own, past and presentwith comments on welfare queens, workfare, and preemployment testingthe emotional nature of the work ethicwork in the ancient worldTocqueville, Thoreau, and Whitman on work in America and the trouble with fathersslacker moviesacademic work and other questionable laborsanswers to What makes good work good? and What did Jesus do?hippies and other dropoutsand the Way of the Slacker.

In which the Idler, the worlds first slacker, appears in 1758Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Johnson usher in the modern worldand the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions reshape the nature of work.

In which the Lounger, the Idlers spiritual brother, appears toward the end of the eighteenth centuryMeander, Abel Slug, Esq., and other icons of lounging have their sayand Rip Van Winkle sleeps through his career.

IV LOAFERS, COMMUNISTS, DRINKERS, AND BOHEMIANS

In which the Romantic hero, the loafer, and other odd variants in the early nineteenth century make their appearanceKarl Marxs son-in-law thinks the old man works too muchworkers like to leave for a drink at the bar several times a daythe campaign for shorter hours starts to make headwayHerman Melville loafs in the South SeasBartleby the Scrivener prefers not toand Bohemia arrives in America.

In which the doctors decide that overwork is a problemJerome K. Jerome takes a leisure trip up the Thamesthe flneur and Saunterer make their bowsOscar Wilde declares that doing nothing is the height of human achievementthe tramp becomes a hero and a social problemand Theodore Dreiser flirts with failure but decides to work instead.

In which the slacker becomes the villain of World War I and the hero of modernist literaturemore fathers and sonswork goes out of fashion for the poor and becomes fashionable for the richbooms and bustsAmericans are told they need to Sweat or Die!The Great Gatsby shows how to reconcile Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Johnson in modern timesand AI Jolson sings Hallelujah, Im a Bum!

In which new generations of the disaffected reinvent the slacker wheel as the world of work changes once againJack Kerouac and his dad have a falling outthe Man in the Gray Flannel Suit gets ahead and feels bad-Organization Man, white-collar workers, and other conformist losersand women try on the flight from commitment.

VIII DRAFT DODGERS, SURFERS, TV BEATNIKS,

AND HIPPIE COMMUNARDS

In which George W. Bush tries to go mano a mano with Pappywaves of new slacker types cycle through popular culture and hip subculturesMaynard G. Krebs, Gidget, Abbie Hoffman, and Baba Ram Dassdropping outback to the farmcommunal slackingstealing booksand other ways to get money for nothing.

In which slackers finally get their proper namethe game room rules the workplacekids make movies instead of workingthe Church of the Sub-Genius reinvents the loungerthe slacker novel has yet another renaissancewe visit the slackers of Japan and find that globalization in fact has made us all kinthe poor stay poorthe Internet and Anna Nicole Smith show us the Way of the Slackerand the author reports that his son, Cody, has left the couch.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Paul Mandelbaum and Laurie Winer were ideal readers for the whole and are okay poker players. Leo Braudy, Ken Cmiel, Jay Fliegelman, and Rob Latham helped materially and, I dont know what you call itspiritually, I guess. Jeffrey Charis-Carlson, Corey Creekmur, Kathleen Diffley, Loren Glass, Cody Lutz, Steve Molton, Angie Nepodal, Laura Rigal, Sean Scanlan, Harry Stecopoulos, Erica Still, Jeffrey Swenson, and Keith Wilhite read large chunks of it, and I thank them for their comments. On the way out the door, thank you to Brooks Landon and Ed Folsom. Melanie Jackson, thank you for everything, and Lorin Stein, youre no slacker, far from it. Jesse and Yarrow: youre my favorite daughters, and I love the way you work.

I

CODY ON THE COUCH

I n which the author confronts his sons lazinessand remembers his own, past and presentwith comments on welfare queens, workfare, and preemployment testingthe emotional nature of the work ethicwork in the ancient worldTocqueville, Thoreau, and Whitman on work in America and the trouble with fathersslacker moviesacademic work and other questionable laborsanswers to What makes good work good? and What did Jesus do?hippies and other dropoutsand the Way of the Slacker.

Every man is, or hopes to be, an Idler.

SAMUEL JOHNSON, THE IDLER, APRIL 15, 1758

I began this book shortly after my son, Cody, at the age of eighteen, moved from his mothers house into mine. His plan was to take a year or two off before beginning college, and he had come to Los Angeles with uncertain plans. His older sister had moved out a couple years earlier and had a fairly glamorous Hollywood job, and he thought maybe he could get a foot in that door or, perhaps, end up in a hot new band and become a big (alternative) rock star. Either way, he was coming west, the young man, and I looked forward to having him in the house full-time. For a decade he had lived with me only during summers and vacations, and although ours was by all measures a very good relationship, neither of us knew whether we would feel the same ratio of success and failure, the same levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with each other, if we lived together all of the time. We were both excited (if a little apprehensive) about this new chapter in our lives. Whatever else, I was glad that I could give him a base from which to chase a dream or two.