Table of Contents

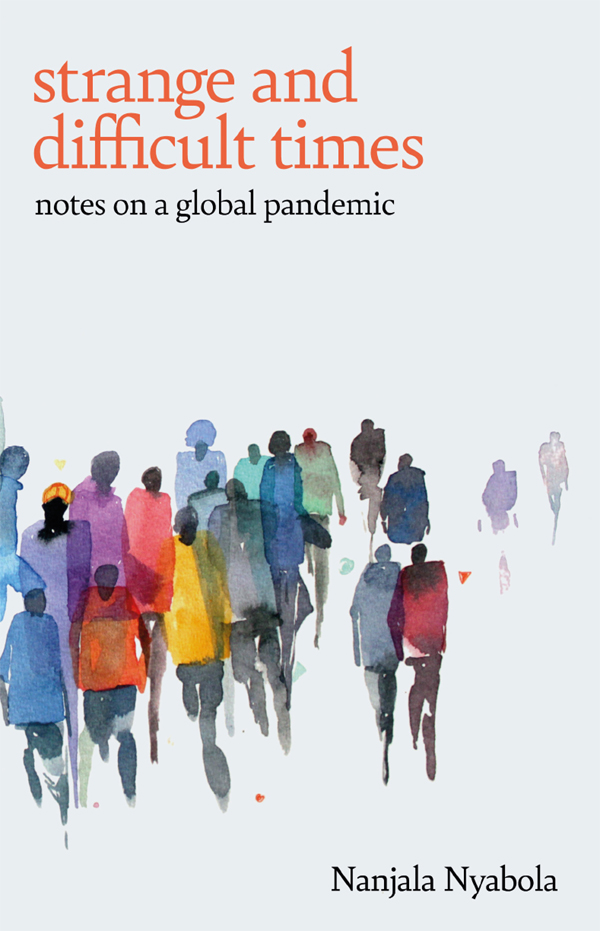

STRANGE AND DIFFICULT TIMES

NANJALA NYABOLA

Strange and Difficult Times

Notes on a Global Pandemic

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2022 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA

Copyright Nanjala Nyabola, 2022

All rights reserved.

The right of Nanjala Nyabola to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787387805

A version of was published in part in The Nation as Vaccine Nationalism Is Patently Unjust (2021) and in part in Al Jazeera as Africas vaccine crisis: Its not all about corruption (2021).

This book is printed using paper from registered sustainable and managed sources.

www.hurstpublishers.com

For Lorna

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

In his 1947 novel The Plague, French author Albert Camus expresses the morbid mundanity of a pandemic. The trouble is, Camus writes, there is nothing less spectacular than a pestilence and, if only because they last so long, great misfortunes are monotonous. More than a story about disease, Camus fictional account of how the bubonic plague swept through a small town in French Algeria during the 1940s is a story about the fears and anxieties of human beings dealing with a collective challenge that they dont fully understand. How does it change their relationship with authority? How does it change their relationships with each other? How does it change their perception of risk and the kind of things they are willing to give up as they confront it? What are the things they are unwilling to let go of? What is it about these large-scale disasters that collides so violently with the way we think about what it means to be human, that makes us channel more energy into separating ourselvesinto the contaminated and the uncontaminatedthan into coming together to fight the disease?

Pestilence is in fact very common, Camus writes, and I underline furiously, but we find it hard to believe in a pestilence when it descends upon us. I read The Plague while I was myself in quarantine after a positive PCR test for COVID-19. Thankfully, I was infected less than a month after receiving a booster vaccine, so my symptoms remained mild. For two years, I had managed to successfully evade the disease, first under strict self-quarantine in Nairobi, and then by building myself a travel plan based on the guidance provided by experts and the prevalence of the virus in different countries at the time. However, just when I was on the road for a Christmas vacation in December 2021, a new and highly contagious strainOmicronwas discovered, and many protections we had previously relied upon turned out to be less effective. The hollowness of the promises about the whole world being in this together became truly evident when the entire African continent was branded with a scarlet letter of contagion by several countries, notably in Europe, despite the fact that COVID-19 was far more widespread there. The only thing the Botswanan and South African scientists, who discovered the Omicron variant, did was warn the world that the virus had changeda change later found to have already been underway in Europe before it was detected in Africa. But it was enough for countries and regions to ban travel from almost all African countries.

The after that we had all desperately hoped was upon us after two years of lockdowns, restrictions and intense sacrifice was once again out of reach; the world was looking more and more like a place in which being black and African was enough for baseless fears of contagion.

What should a book reflecting on a pandemic be about?

When people ask me what I do, the most concise answer I can offer is that I am a storyteller. So much of what we all do in our daily lives as individuals, or as members of a community or a society, is in response to story, specifically the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Storytellers are not just entertainment at childrens parties. Storytellers are people who try to give order to the different threads of our existence. Storytellers are people who infuse our experiences with the flavour of our hopes and aspirations, simply by naming them and placing them in relation to those of others. Storytellers are people who fix history in place so that, at the very least, we can try to remember things correctly. Storytellers come in all forms, whether journalists, historians, novelists, essayists or poets. The composition might differ, but fundamentally we are all trying to do the same thing. We are trying to verbalise things that we feel need to be said, lest they be forever lost to time or memory. For me, the form of the work has always been less important than the function of the work. I am a storyteller, not just because of a particular type of work in a particular moment in history, but because I use narrative to try to make sense of the world for myself and for others.

What is the story of the pandemic about?

A moment like this, where history draws a bold line between the before and the after, is a call to action for artists and storytellers. Life invites us to do what so many are unable to do because of the way in which our societies are structured: to stop time, mark moments and invite reflection. Renowned African American author Toni Morrison once said that in times of crisis, the artists must get to work. And this pandemic, in which art emerged so ferociously as an outlet and a balm for so many, only to be neglected in the efforts to rebuild, is a moment for those who create and those who tell stories to remind us of why art matters. A book about a pandemic should not just be about the crisis; it should illuminate what the crisis meant and what the crisis could mean.

In March 2020, I was on one of the last flights from Cape Town to Nairobi before both cities were locked down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, for what turned out to be at least a year. Of course, I didnt know this at the time. Like most people, I believed the governments when they told us that we would only have to bear a few months of sacrifice to ride out the worst of the wave before we could all get back to normal. Even though we had witnessed the disease tear through Asia, then Europe, and then finally North America, somehow, four months in, Africa had been spared the worst of it. The lockdown in South Africa was announced several days after I returned to Nairobi; I cancelled a few appointments and settled into a rhythm of virtual book clubs and meet-ups with friends, while restricting my social bubble only to family. It was supposed to be three months. But four months later, listening to the eerie silence of a Nairobi without its nightlife, unsure of how work would continue, it was clear that this was not a temporary interruption. This was a seismic shifta giant crack in the ground between the before and the after.

A book about the pandemic should be a dirge for everything we lost and a sonnet for everything good we learnt about ourselves.

In the third year of the crisis, we still find ourselves stuck between analogy and speculation, knowing that the disease has fundamentally changed our world, but not knowing when we can finally declare it over so we can begin to grapple with what after might look like. We know that there was some good revealed about our shared humanity, but there was also a great deal of bad. We saw generosity and selfishness at scale. We saw racism and ableism tip the scales on how the value of different lives could be measured, all in the service of this big nebulous totem we call the Economy. We said goodbye to people we loved fiercely far too soon. We were reminded that doctors, teachers and nurses are the wheels on which our ideas of civilisation roll, only to watch those with power deny them the very basics they needed to be kept safe. We argued passionately with our friends and family about what it means to do Science. The pandemic, like all pandemics before, posed a question, asking us why we built the societies we lived in. At the start, we were promising, but by the endor perhaps more accurately the middle, because we still dont really know how this all endsit was clear that we were struggling with the course material.