Wonder Foods

Darra Goldstein, Editor

Wonder Foods

THE SCIENCE AND COMMERCE OF NUTRITION

Lisa Haushofer

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2023 by Lisa Haushofer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Haushofer, Lisa, author.

Title: Wonder foods : the science and commerce of nutrition / Lisa Haushofer.

Other titles: California studies in food and culture ; 80.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2022] | Series: California studies in food and culture; 80 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022024990 (print) | LCCN 2022024991 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520390386 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520390393 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520390409 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: NutritionEconomic aspects. | Food industry and tradeEconomic aspects. | FoodTechnological innovationsHistory.

Classification: LCC TX 353 . H 334 2022 (print) | LCC TX 353 (ebook) | DDC 338.4/7664dc23/eng/20220803

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022024990

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022024991

Manufactured in the United States of America

32 31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Publication supported by a grant from The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven as part of the Urban Haven Project.

To my family

Contents

Illustrations

Introduction

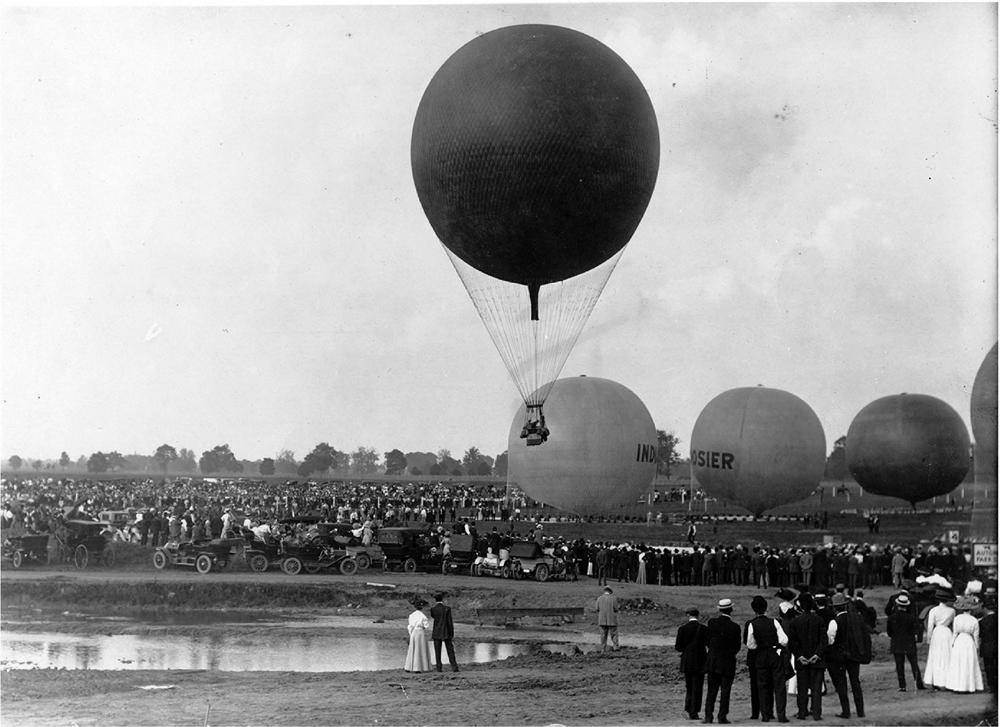

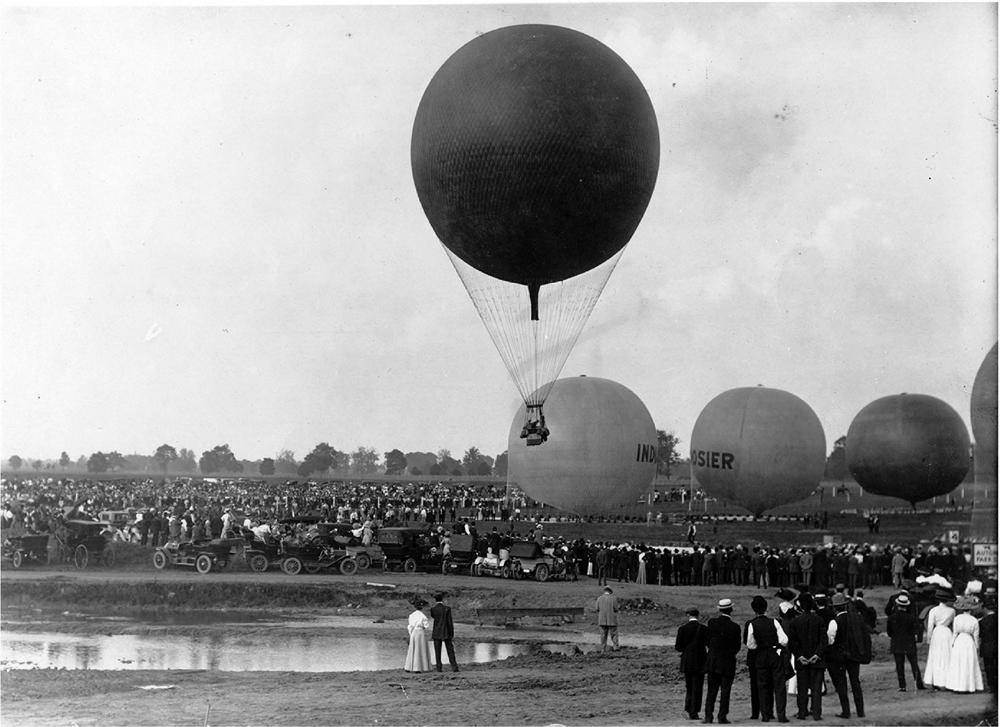

BALLOONS OVER INDIANAPOLIS

THE YEAR WAS 1921 , and the afternoon sky over Indianapolis was filled with balloons. Like bloated Easter eggs, they moved between mountains of clouds and formed ever-changing clusters of color against the white horizon. A gentle breeze blew in from the southeast, defying predictions from the night before that had threatened to thwart the spectacle with strong winds. From all across town, over forty thousand people had come to witness the balloons takeoff for the international balloon race, crowding nearby streets, roofs, and even treetops, in order to catch a glimpse of these wonders of modern technology. An eerie quiet had descended upon the rest of the city, as businesses and industries were forced to shut down for the day. As the announcers barked out the names and state affiliations of each departing balloon, the crowds cheered and waved at the crews, who busily fired their vessels burners and proudly descended American flags from the rims of their ascending baskets. The crowd lingered long after the last balloon had been waved off and the last patriotic tune of the military band booked for the occasion had faded into the evenings silence. They stood and watched as the flames became smaller and smaller, and finally disappeared, like big fireflies chasing each other over the edge of eternity.

Elmer Cline was in the crowd that day. For the rest of his life, he would recall the floating balloons in the air, and the sense of awe he felt at their sight. He especially remembered their vivid primary colors. Cline was a rational man, a businessman, not easily moved by spectacle. In fact, his profession often required him to look beyond the kinds of displays that might dazzle others. He was deputy manager of merchandising development of the Taggart Baking Company, and as such, he had constructed many advertising He was, in short, a man not naturally prone to sentimentality.

But on that afternoon in 1921, Elmer Cline was inspired. Watching the International Balloon Race take off from his hometown, he had felt a sense of wonder. There was no better way to describe the feeling that had overcome him: a mixture of admiration, surprise, and disbelief; amazement at the technical and scientific achievement evident in the display; astonishment at the quasi-miraculous powers at work in overcoming seemingly unchangeable laws of nature. He allowed his mind to conjure up images of a world transformed through the ability to traverse ever greater distances at ever greater speed, unimpeded by the ballast of terrain or exhaustible animal power. If gravity could be overcome so effectively, who knew what other earthly forces could be outmaneuvered.

Ever the pragmatist, Cline applied the profound impressions of that afternoon to a work problem he had been mulling over for some time. He was charged with finding a catchy name for his baking companys newest loaf of bread. While attending the balloon race in 1921, Elmer Cline had found the solution: he would name it Wonder Bread. Over several days, the word wonder appeared in a series of newspaper advertisements, in the same tickler fashion Cline was known for, leaving consumers to wonder what the product might be.

To this day, the red, blue, and yellow balloons of that afternoons Indianapolis sky, immortalized on the breads iconic wrapper, form an integral part of Wonder Breads advertising lore. So does Clines moment of wonder: again and again, the story of inspiration striking as the balloons rose into the sky has been rehearsed in company literature, magazine stories, and popular histories. It is a captivating origin story, laced with serendipity, awe, and ingenuity, attributes so often associated with scientific discovery and progress.

FIGURE 1. Balloon race, Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 1909. Bass Photo Co. Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

But as with a well-yeasted loaf of bread, there are holes in the story. For one, there was no international balloon race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1921. International balloon races had been organized in different locations around the world since 1906, including in the United States, but the 1921 race took place some four thousand miles away in Brussels, Belgium, and Wonder Bread was launched before it took place. It is not unlikely that Cline had visited either or both of those races, and still remembered the scenes in 1921. But if this was the case, his Eureka moment was not exactly the one evoked in the promotional tales.

A more likely explanation is that Cline and his baking company had intended to tie the launch of Wonder Bread to an international balloon race He even declared that there was no city in the United States that should, under present conditions, undertake to provide gas for this purpose; such a use of natural resources would, in his mind, be criminal.

Regardless of how the story emerged, this mythical start to life befits a product that would remain suspended between fact and fiction, between science and superstition, between substance and spectacle, throughout the course of its eventful career. If advertisements of Wonder Bread were to be believed, the loaf was not just another ordinary staple, but a kind of miracle food, a magic bullet that would solve deeply rooted issues in US dietary culture and in US society more broadly. The Chicago Worlds Fair of 1934 celebrated Wonder Bread as an object of scientific and technological ingenuity, a promising commercial venture, and a potential solution to broader public health challenges. By promising to nourish better, to contain superior nutritional value, and to be more digestible, Wonder Bread proposed a convenient way out of seemingly immutable and difficult social and natural realities. Here, in short, was a hero to save the day (and we do like our heroes to come with unusual origin stories, like Jesus, or Hebe, or Superman).

But there was a dark side to the white loaf. Wonder Breads vision of a better dietary future was highly selective, and it built on (and perpetuated) transgressions of the past. Advertisements of the bread matched the whiteness of the loaf with images of almost exclusively white, middle-class young women, men, and children.