Michael Palin

ON THE ROAD AGAIN

THE FIRST BOOK I WAS EVER GIVEN WAS TALES FROM THE Arabian Nights. I still have it, inscribed To Michael, with love from his Daddy, 5th May 1950. Its a chunky hardback with an alluring cover, showing a girl reading from an open book to an entranced boy; behind them one of the Forty Thieves, sword in his mouth, peers menacingly out from the top of a tall jar. Below them stretches a wide blue sea beside whose shore rise the domes and minarets of a mosque. The cover illustration, and the stories within, not only captivated and enthralled me, they defined in my seven-year-old mind what foreignness was. It was my first experience of the allure of other places.

The world so seductively and dramatically conjured up by A.E. Jacksons colour plates was an Arab world, a Middle Eastern world, and yet, in all my subsequent travels, it remained a world I knew least that is, until 2022, when my travel plans took an unexpected turn.

For some time various obstacles had prevented me going anywhere at all, including surgery to repair two leaky valves in my heart, followed by the Covid pandemic and the protracted shutdown of world travel. I sat at home, making only two journeys in eighteen months one as far as Bradford and the other, much more ambitious, all the way to Scotland. My atlas was gathering dust and I was hanging my boots on an ever-higher peg. I worried that, if this went on much longer, I might lose the will to move.

With Neil Ferguson, who directed my series in North Korea five years ago, I tried to keep the flickering flame of another journey alight. Together we looked hungrily at maps and guidebooks, planning journeys more in hope than expectation. We were particularly taken by the idea of travelling to the Middle East a part of the world neither of us was that familiar with. We even got as far as drawing up quite a detailed itinerary for a series on Syria. Unfortunately, our plans were stymied at the last minute when the Syrian authorities found that I had given money to the White Helmets. That volunteer organisations work to bring relief to those in bombed and damaged areas was anathema to the Assad regime, and we were denied permission to film.

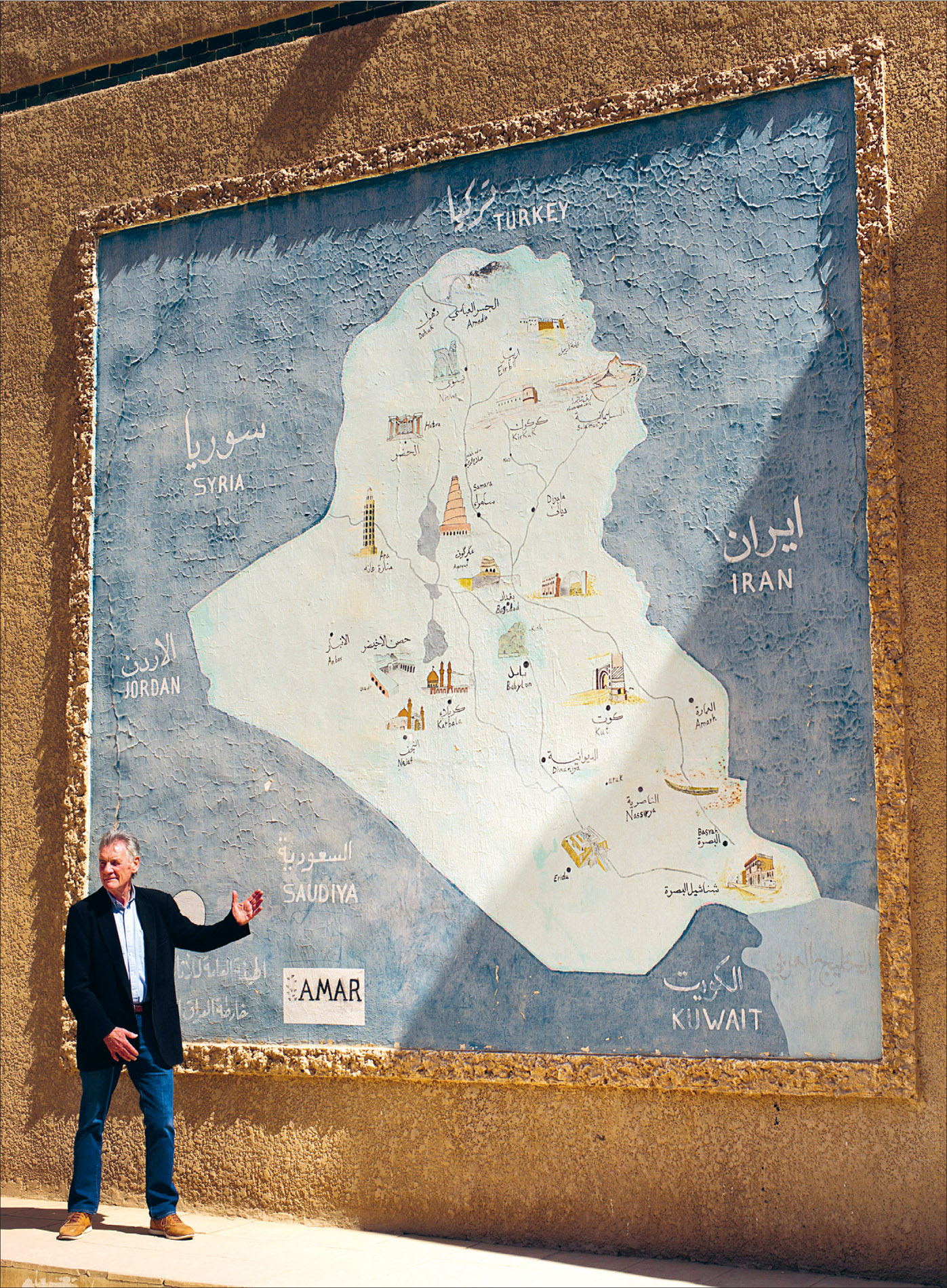

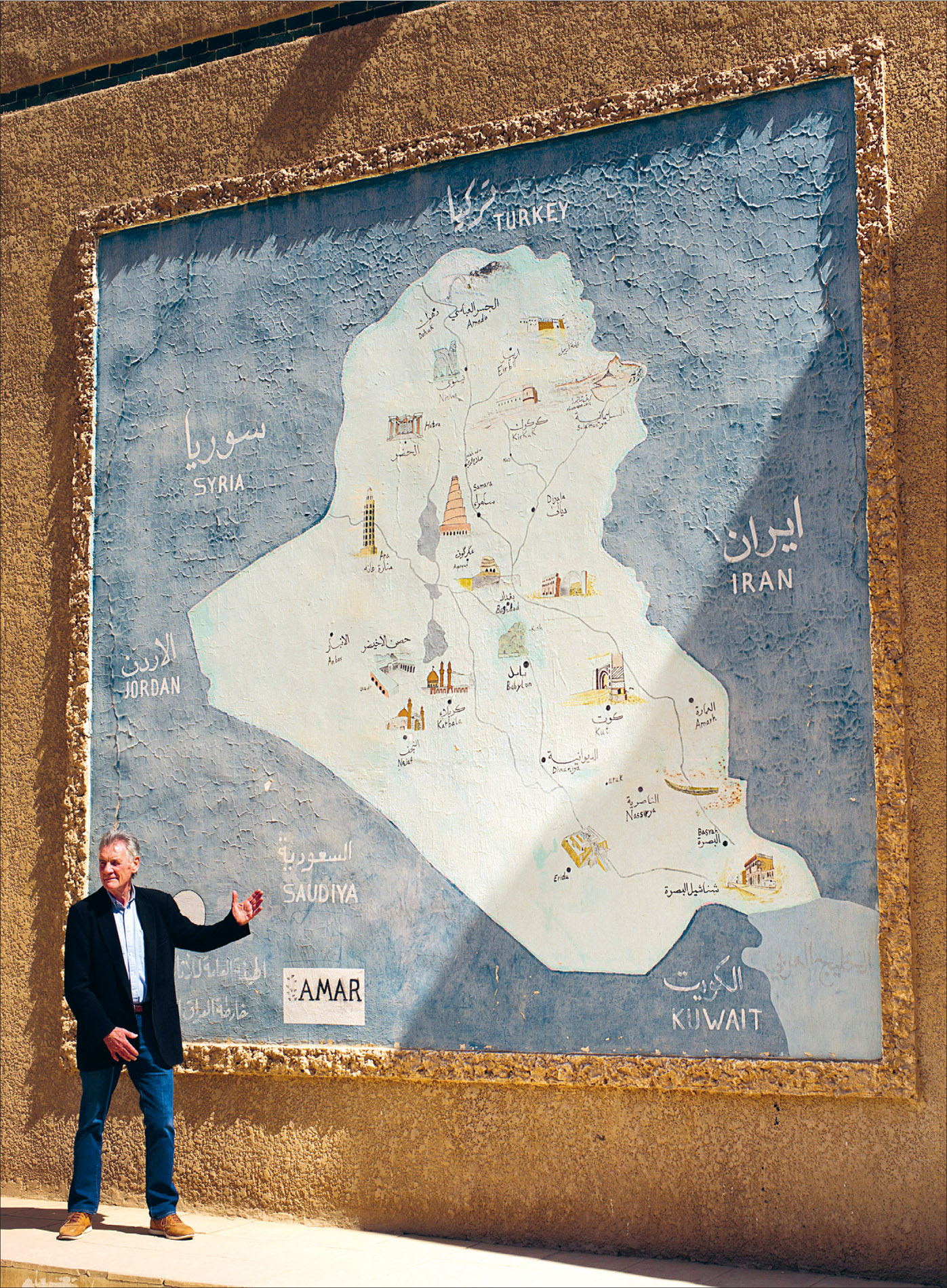

But before finally folding away the map and bidding farewell to the Middle East, my eye was caught by one of the countries that bordered Syria. Iraq. A number of evocative names sprang out at me Babylon, Baghdad, Karbala, Ur of the Chaldees and two rivers whose names recurred repeatedly throughout ancient history, the Tigris and the Euphrates.

The Greeks called the region Mesopotamia (The Land) between Rivers. So fertile was the land fed by these rivers that ten thousand years ago it encouraged hunter-gatherers to abandon their previously nomadic way of life and become farmers, creating in the process the worlds first settlements. By 5000 BCE some of the settlements had become the worlds first cities. These grew into empires with resounding names Sumeria, Babylon, Assyria. Though they rose and fell in war and bloodshed, they achieved previously unheard-of levels of sophistication: the first written documents, the measurement of time in units of sixty, complex and magnificent architecture, and the wheel, all had their origins in Mesopotamia.

Yet in recent years these lands had witnessed chaos and dysfunction: the brutal dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, invasion by US- and UK-led forces, internecine conflict between the countrys different religious and ethnic groups, and the rise and fall of Islamic State. Iraq was written off by the worlds media, and demonised by George W. Bush as one of the three countries on his axis of evil. The cradle of civilisation had become the heart of darkness.

Perhaps this grim tide of events should have dissuaded me from wanting to go. In fact, it made me all the more determined. I wanted to understand how the birthplace of civilisation should have become so riven by conflict. I realised I was as fascinated by the regions present as I was by its extraordinary past. I decided that Iraq should be the focus of my next expedition.

Neil and I agreed that our route through Iraq should follow the river Tigris one of the countrys ancient and modern lifelines from source to sea: from the mountains of southern Turkey to the shores of the Persian Gulf.

Then, only weeks before we were due to leave, and just as the channels of world travel began to flow again, news came through of Russian tanks rolling into Ukraine. The grip of the pandemic had loosened, only to be replaced by the possibility of a world war.

We briefly wondered whether we should postpone our trip. But the thought that Iraq, too, was a place of conflict whose story could so easily be lost amid competing headlines persuaded us to stick with our plan. Almost exactly two years from the day Boris Johnson announced the first lockdown, I was piling my bags into a car, waving farewell to my infinitely tolerant wife and, once again, heading for Heathrow.

What follows is a day-by-day account of our journey into Iraq, kept in a notebook and on a voice recorder. I owe a great debt of thanks to Steve Abbott, Paul Bird and Mimi Robinson at Mayday, to Peter Griffin for keeping me safe and healthy, and James Willcox of Untamed Borders for his Iraqi expertise. And most of all to Neil Ferguson for planning, directing and inspiring the film, and my wonderful crew, Jaimie Gramston, Ben Crossley and Doug Dreger, not forgetting Will Smith at ITN and Guy Davies at Channel 5 for their unwavering support and encouragement, and Nigel Wilcockson my tolerant, patient publisher, who saw this book through.

IM IN ISTANBUL. ITS A BITTERLY COLD MORNING. Something I hadnt expected on a trip to Iraq. Our hotel is small, neat and feels more like a ski lodge. Snow has been partly cleared from the driveway, leaving deadly patches of slipperiness.

Its still dark.

No time for breakfast. Straight to the airport. Opened less than four years ago, it covers a vast area of what was once state-owned forest. Everything about it is big and swanky. The control tower is over three hundred feet high and in the shape of a tulip, Turkeys national flower. The place is packed.

Were on an internal flight, which ought to make life straight-forward, but we swiftly discover that every piece of our filming equipment which was laboriously scrutinised yesterday when we arrived from London has to be laboriously scrutinised again. The combination of background noise, breath-stifling protective mask and lack of breakfast hits me suddenly and after I get to my feet I find myself so unsteady that I have to pause and reach for support.

Next page