Contents

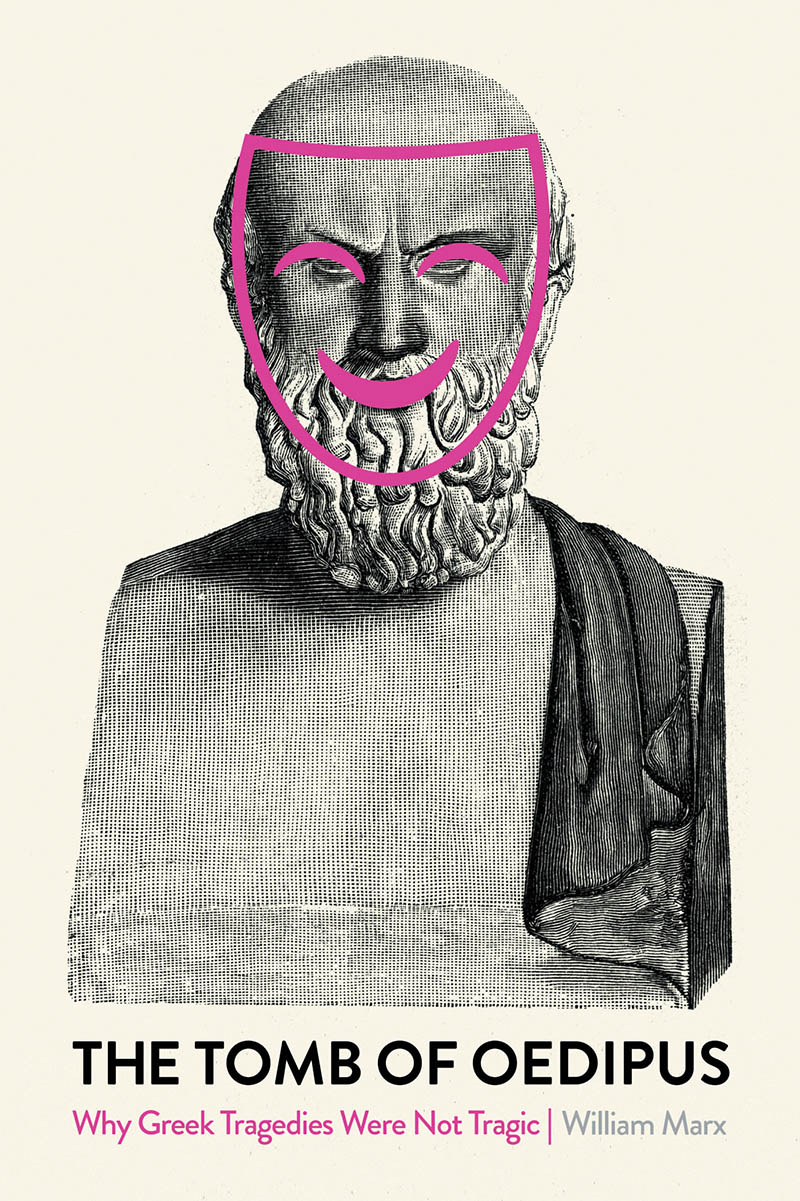

The Tomb of Oedipus

William Marx is a French writer and scholar, professor of comparative literatures at the Collge de France, a member of the Academia Europaea, and an honorary fellow of the Institute of Advanced Studies in Berlin. His books, The Hatred of Literature among them, have been translated into ten languages.

The Tomb of Oedipus

Why Greek Tragedies Were Not Tragic

William Marx

Translated by Nicholas Elliott

This English-language edition first published by Verso 2022

Translation Nicholas Elliott 2022

First published as Le Tombeau ddipe:

Pour une tragdie sans tragique

Editions de Minuit 2012

This book has been published with the support

of the Fondation du Collge de France.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11217

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-613-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-617-6 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-618-3 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Marx, William, 1966- author. | Elliott, Nicholas, translator.

Title: The tomb of Oedipus: why Greek

tragedies were not tragic / William

Marx; translated by Nicholas Elliott.

Other titles: Tombeau ddipe. English

Description: Brooklyn: Verso, 2022. |

Includes bibliographical references

and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022024390 (print) |

LCCN 2022024391 (ebook) | ISBN

9781788736138 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781788736183 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Greek drama (Tragedy)History and criticism.

Classification: LCC PA3131 .M34313 2022

(print) | LCC PA3131 (ebook) |

DDC 882/.0109dc23/eng/20220611

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022024390

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022024391

Typeset in Sabon by Biblichor Ltd, Scotland

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

In one of his most famous stories, Jorge Luis Borges describes the philosopher Averross inability to understand the meaning of the two principal words in Aristotles Poetics: comedy and tragedy. In the Arab civilization of the twelfth century, there is no theatre: Averros has never seen a play; he knows absolutely nothing about it.

His failure would be cruel enough as it is, but is exacerbated by a particular irony: in the courtyard of the house, children play at imitating adults. The philosopher distracts himself by watching the children, never suspecting that he is looking at the object of his search: the secret of theatre is right before his eyes, and he does not see it.

Faced with Greek tragedy, we are all like Averros, but unaware of our ignorance. At least the Arab philosopher knew that he did not know. For our part, we think we know tragedy: we have read and studied it at school, seen it on stage, and made the pilgrimage to Athens and Epidaurus. Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides are more than names to us: we know their work, we have enjoyed it and sometimes even found it admirable.

So? Whats the problem?

The fact is that none of all this really makes up Greek tragedy or Attic tragedy, to be more precise. At best, what we know are its vestiges. Astounding vestiges, surely, which as a whole form one of the greatest achievements of the human spirit. But vestiges nonetheless.

Twenty-four centuries have passed, and all that is left are ruins. Ruins so beautiful that we think were dealing with the actual works, as if the Venus de Milo were not missing two arms. A terrible illusion.

What happened between Greek tragedy and us? Everything. Obviously, language, religion, and culture are no longer the same. The texts, documents and monuments have nearly all been lost. Only a few scraps have survived this total catastrophe.

But thats not all: between tragedy and us, literature came along. For a little more than two centuries, we have been living with an art of language which we have an unwitting tendency to apply to everything that existed before. We read ancient texts through the insidious filter of an autonomous art, intended to be universal, of a superior intellectual level, and detached as much as possible from its context the places, periods, and gods. Yet no such literature existed in the Athens of the fifth century BCE.

So what was there? To try to find out is to go in search of aliens: should Martians one day arrive to perform their plays before our amazed eyes, they would not appear more exotic to us than the masterpieces of Aeschylus and Sophocles would, if we were only willing to see them for what they are or if we could rediscover them as they were.

The solution is to get rid of received ideas. To launch into a process of defamiliarization. To learn what tragedy is not. To approach it in a vacuum. To explain it this only seems like a paradox by its mystery.

When a crime has been committed, the leading suspect is the last witness to have seen the victim. We will proceed in the same manner. We will start from the last known tragedy, the last witness of the form: Sophocless last play, which is also, by historical happenstance, the most recent of the tragedies preserved (but not the last across the board: countless tragedies were subsequently performed in Athens, though all have since been lost).

To confer a particular meaning upon the play for that sole reason would be an error: Sophocles could not imagine that it would become the ultimate specimen of an art form whose actual end would only come a few centuries later. Yet what is false as a historical reality holds a certain truth as a symbol: like it or not, to us Oedipus at Colonus is the tomb of Greek tragedy.

It is, indeed, a doubly posthumous work. By 401, the year it was staged, Sophocles had already been dead five years, and tragedy itself was in the process not of dying out, but of changing radically (Aristophaness The Frogs bears witness to this crisis). Perhaps the Ancients were right to choose it as the chronological close of the canon.

Oedipus at Colonus is the other Oedipus. In Oedipus Rex, the hero who has become the ruler of Thebes sees the monstrous past of which he is the product resurface. Sophocless final play tells his version of what happened next.blind and helpless Oedipus arrives by chance in Colonus, a suburb of Athens. After a few incidents, he receives the official hospitality of the Athenians. His wandering life comes to an end, as does his life itself, in miraculous, totally unexplained circumstances. Ultimately, all that is left of Oedipus at Colonus is his tomb, but it is a supernatural tomb, an invisible tomb that cannot be found. It is as inaccessible as Greek tragedy is to us.

What does this tragedy without tragedy tell us about tragedy in general? Here are four successive theories or rather, four enigmas:

tragedy is a matter of places, to which it is indissolubly bound, and without these places it is (nearly) nothing: a symbolon missing its essential half;

tragedy has nothing to do with what is commonly referred to as tragic: we cannot have a general idea of what it was, what it meant, or the world-view it expressed, because the available corpus is the product of an ideologically biased transmission;