Genealogy of the Tragic

Genealogy of the Tragic

GREEK TRAGEDY AND GERMAN PHILOSOPHY

Joshua Billings

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

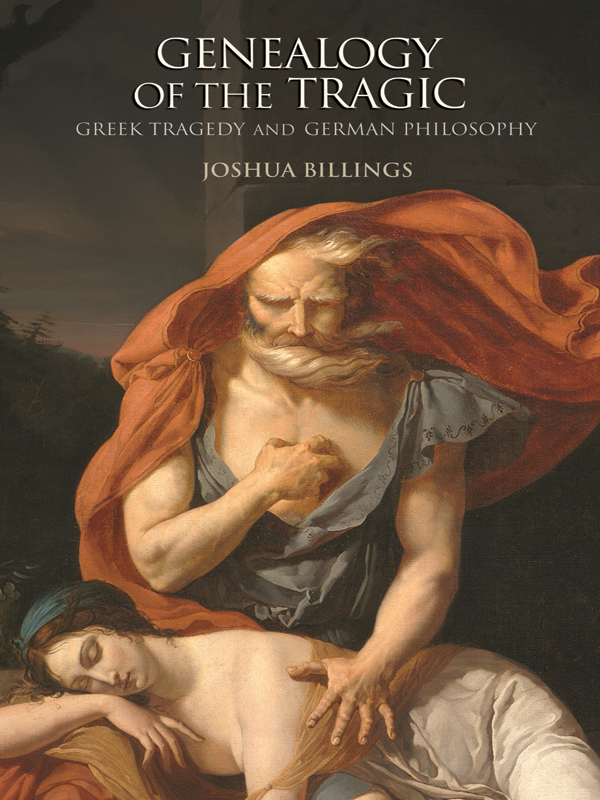

Jacket art: Oedipus at Colonus, Fulchran-Jean Harriet, 1798. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund 2002.3.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15923-2

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my parents, Susan and Andy, and my brother, Gabe

.

,

.

The Oedipus at Colonus of Sophocles.

You found, Sophocles, great renown [kleos] among wise people [sophois].

For entwining the lamentations of others,

You made us all sorrowful.

Scholiastic epigram to Oedipus at Colonus

Viele versuchten umsonst das Freudigste freudig zu sagen

Hier spricht endlich es mir, hier in der Trauer sich aus.

Many tried in vain to say the most joyous joyously,

Here finally it reveals itself to me, here in mourning.

Hlderlin, Sophocles

Contents

Preface

T RAGEDY, P LATO TELLS US (Laws 658D), is a subject for young men. Since middle school, I have continually been drawn to tragedy in performance and on the page, and in the ten years since entering university, Greek tragedy has been the center of my intellectual life. Most of all, I have wondered what it is about these works that makes them speak so profoundly to my own experience and sense of the world. In figures like Hlderlin, Nietzsche, and Benjamin, I found young men who had answered these questions with staggering brilliance and insight, and enriched my own appreciation and understanding. This book arose out of my effort to see tragedy through their eyes. As an investigation of an investigation, it has led far astray from the phenomenon itself, but it may be, as Hlderlin writes, that it is only aus linkischem Gesichtspunkt (from an awkward point of view) that we can hope to grasp the most important questions of meaning. Reading tragedy through Idealism may not make us more Greek readers (whatever that would mean), but it can make us more authentically modern ones, in the sense of reflecting on the timeliness and untimeliness of Greek tragedy for us. And I believe we need tragedynot only as scholars and teachers, but as beings thrown into existence and one another.

I have had extraordinary good fortune in mentors, colleagues, and institutional homes, and the generosity with which I have been treated makes the flaws of the work presented here all the more glaring. This project began as a dissertation in Classics at Oxford, where Oliver Taplin and Fiona Macintosh supervised my work. Despite the unconventionality of the project, they welcomed me warmly and advised my research with extraordinary perceptiveness. Oliver asked me, at a number of crucial moments, vital and unexpected questions, while Fiona showed an uncanny ability to foresee where my research was going long before I did. During a year in the Oxford German department, and for some time after, Manfred Engel guided my halting steps in German intellectual history and offered me a standard of rigor that I can only hope to have satisfied. At intermediate stages, Gregory Hutchinson, Tim Whitmarsh, and Patrick Finglass all served as assessors, and I benefited from their feedback on early drafts. The dissertation was examined by Glenn Most and Felix Budelmann, and their thoughtful comments directed the revisions in which the book assumed its current form. To Glenn especially, I owe special thanks for his continued guidance, and for the model his scholarship has provided me.

Four colleagues endured the entire dissertation-cum-book at different stages, and offered me crucial advice. Miriam Leonard has been a mentor and friend from early on in the project, and I have continually learned from her scholarship, conversation, and penetrating comments on written work. Constanze Gthenke read and listened to too many stages of this work to count, and offered thoughtful suggestions, probing questions, and warm encouragement. Jim Porter was a formative influence in print long before I found him to be a generous colleague, and his reading of the full manuscript was pivotal in clarifying and honing the central argument. Most recently, Allen Speight kindly agreed to read the entire manuscript, and offered extraordinarily perceptive comments, which have greatly improved the rigor of my interpretations and argument.

This project was in many ways inspired by my undergraduate mentors, Albert Henrichs and John Hamilton. In different ways, their approaches to scholarship have been lodestars for my ownAlberts for the warmth and open-mindedness with which he approaches questions of meaning, ancient and modern, and Johns for the imagination and rigor he brings to philology. Renate Schlesier has welcomed me to Berlin numerous times over the past six years, and I have learned from her in every exchange. Michael Silk has been a wise counselor and good angel at several important moments. Since my time in Cambridge, I have benefited from the good friendship and extraordinary intellectual energy of Simon Goldhill.

I have been further lucky to find stimulating interlocutors in Matthew Bell, Angus Bowie, Jessica Blum, Rdiger Campe, Roger Dawe, William Fitzgerald, Renaud Gagn, Susanne Gdde, Nora Goldschmidt, Emily Gowers, Edith Hall, Katherine Harloe, Richard Hunter, Daniel King, Oliver Leege, Pauline LeVen, Charlie Louth, Roger Paulin, Andrei Pesic, Peter Pesic, Martin Ruehl, Anette Schwarz, Scott Scullion, Richard Seaford, Amia Srinivasan, Oliver Thomas, Anna Uhlig, Marie-Christin Wilm, and Larry Wolff. Lucas Zwirner served as much more than a last pair of eyes before print, and I benefited greatly from his comments on the near-final manuscript. Finally, though they were not directly involved in this project, I wish to record my gratitude to four undergraduate teachers, from whom I learned many of the skills that went into this work, and whose kindness has buoyed me at important moments: Jim Engell guided me through my first effort at producing scholarship; Greg Nagy opened my eyes to possibilities for thinking imaginatively about Greek literature; Hugo van der Velden showed me a way of looking; and Helen Vendler taught me to read poetry.

Of the institutions that have facilitated this work, my first thanks goes to the Rhodes Trust, to which I owe the opportunity to study at Oxford. Merton College and the Oxford Faculties of Classics and Medieval and Modern Languages proved stimulating environments in which to live and work, and offered financial assistance for research travel (including grants from the Craven Committee, the Zaharoff Fund, and the Simms Fund). A semester exchange at the Maximilianeum in Munich was particularly fruitful, in large part because Friedrich Vollhardt, Arne Zerbst, and the Schelling-Kommission of the Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften welcomed me into their midst and provided an exciting ferment for work on German Idealism. St. Johns College, Cambridge offered beautiful surroundings and warm interactions for a year while I turned the dissertation into a book as a Research Fellow, and has continued to be generous and flexible. At Yale, I have found a welcoming home in the Department of Classics and the Humanities Program, and I am especially grateful to Howard Bloch, Kirk Freudenburg, Bryan Garsten, and Chris Kraus, for their goodwill and wise guidance in the transition. A research grant from the Griswold Fund and a publication grant from the Hilles Fund helped me complete final work on the manuscript. Joshua Katz brought this project and me to Princeton University Press and has guided me through the process with warmth and insight, and Rob Tempio and Ryan Mulligan deftly oversaw its publication. Eva Jaunzems provided thorough copyediting, and Jill Harris was a pleasure to work with as production editor. Finally, Dylan Kenny was a careful proofreader.

Next page