FEMALE ACTS IN GREEK TRAGEDY

p. ii: Designer to handle

p. iii: Designer to handle

Copyright 2001 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Foley, Helene P., 1942

Female acts in Greek tragedy / Helene P. Foley.

p. cm.(Martin classical lectures)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-473-1

1. Greek drama (Tragedy)History and criticism. 2. Women and

literatureGreece. 3. Women in literature. I. Title. II. Martin

classical lectures (Unnumbered). New series.

PA3136 .F65 2001

882'.0109352042dc2100-060624

This book has been composed in Goudy Old Style

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements

of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper)

www.pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Duncan, Christian, and Froma

Contents

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK has been a long time in the making. So many individual scholars, students, and institutions have in one way or another helped me to formulate and improve my ideas that I have decided to note contributions to individual chapters locally. Nevertheless, some special thanks belong here. The following have at one stage or another read more than one chapter of the book, and I am profoundly grateful to all of them: Duncan Foley, Richard Seaford, and Christian Wolff; the referees for Princeton Press, Mark Griffith and Donald Mastronarde; and the anonymous referee for the Martin Lectures Committee. The intellectual friendship and personal support of Susan Cole, Carolyn Dewald, Simon Goldhill, Frederick Griffiths, Edith Hall, Natalie Kampen, Marilyn Arthur Katz, Rachel Kitzinger, Dirk Obbink, Robin and Catherine Osborne, Sarah Pomeroy, Cynthia Patterson, Daniel Selden, Alan Shapiro, Laura Slatkin, Susan Stephens, Oliver Taplin, Froma Zeitlin, and the late Jack Winkler have also been critical. Brian MacDonald served as an invaluable copy-editor.

I wish to thank the John Solomon Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and Barnard College, Columbia University, for supporting the writing of this book.

Finally, I am grateful to Oberlin College for inviting me to present the Martin Classical Lectures, for offering me such wonderful hospitality and criticism while I was there, and for permitting me to embed those lectures in a larger study. The lectures themselves dealt exclusively with the issues discussed in part III of the book, but have been changed considerably to fit a new format.

I also wish to thank the following presses and journals for permission to publish revised versions of the following articles or book chapters: to Classical Antiquity and the Regents of the University of California for Medeas Divided Self, Classical Antiquity 8.1 (1989), 6185,now revised as III.5; to Routledge (Taylor and Francis) for Anodos Dramas: Euripides Alcestis and Helen, in R. Hexter and D. Selden, eds., Innovations of Antiquity (New York, 1992), 133 60,now revised as IV; to Levante Editori and the editors of Tragedy, Comedyand the Polis for The Politics of Tragic Lamentation, in A. H. Sommerstein, S. Halliwell, J. Henderson, and B. Zimmermann, eds., Tragedy, Comedy and thePolis (Bari, 1993), 10143,now revised as I; and to Oxford University Press for Penelope as Moral Agent, in Beth Cohen, ed., The Distaff Side: Representingthe Female in Homers Odyssey (Oxford, 1995), 93115,now revised as part of III.1,and Antigone as Moral Agent, in M. S. Silk, ed., Tragedy and the Tragic:Greek Theatre and Beyond (Oxford, 1996), 4973,now revised as III.3.

I dedicate this book to three people whose inspiration has been critical to its formation and development: Christian Wolff, who has not only faithfully criticized my work over the years, but inspired my interest in tragedy in graduate school and helped me through my dissertation; Froma Zeitlin, with whom I have been thinking about these issues and whose work I have admired since shortly after our first publications on women in antiquity; and my husband Duncan Foley, whose ability to stand within Classics due to his knowledge of Latin and Greek, and outside as a scholar in another field, has been as valuable as his daily support, love, and understanding.

Introductory Note and Abbreviations

ALL QUOTATIONS and citations from the Greek are from Oxford Classical texts unless otherwise noted. Translations from the Greek are my own if not attributed to others. In general I have Latinized Greek names in order make them more familiar to the nonclassical reader unless doing so would in fact defamiliarize the word (e.g., Core for Kore).

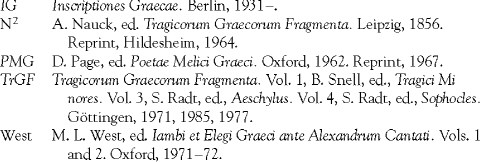

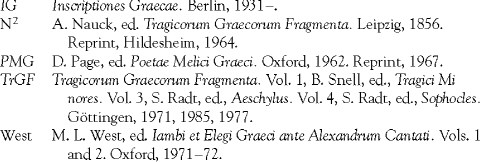

Abbreviations used in the book include the following:

FEMALE ACTS IN GREEK TRAGEDY

Introduction

What is it about women that interests Mr. Jacquot? I was born a man, Mr. Jacquot said, and women are a part of humanity that is at once familiar and very, very strange to me. Its difficult for a man to ask the question, what is a man. Its as if the question just doesnt arise. Or as if we already know the response, and its not necessarily amusing. But a woman can ask herself the question, what is a woman. I try to respond to that question with the female characters I invent and the actresses I film. And they always lead me to further questions.

(French filmmaker Benoit Jacquot, New York Times, August 2,1998)

GREEK tragedy was written and performed by men and aimedperhaps not exclusively if women were present in the theaterat a large, public male audience. and the enduring fascination of these stories of powerful aristocratic families for a democratic polis (city-state) requires explanation.

The study of tragic women is both more limited and in a sense more elusive than that of tragic men. Tragedy at least makes a pretense of knowing what women are and how they should act, and has a repertoire of clichs to draw on in describing them. As a category, women are a tribe apparently less differentiated as individuals than men; paradoxically, they are both more embedded in the social system and marginal to its central institutions. Ideally, their speech and action should be severely limited, since they are by nature incapable of full social maturity and independence (see III.1). At the same time, tragedy generically prefers representing situations and behavior that at least initially invert, disrupt, and challenge cultural ideals. Although many female characters in tragedy do not violate popular norms for female behavior, those who take action, and especially those who speak and act publicly and in their own interest, represent the greatest and most puzzling deviation from the cultural norm.

These female interventions would be less puzzling if they could be explained simply as inversions of the norm designed to be cautionary demonstrations of the cultural consequences of stepping out of line. Yet, as we shall see, this is not consistently the case; and even when it is, the repercussions of female speech and action and the ways in which they are represented raise an unexpectedly broad and disconcerting set of questions. For this reason, recent critics, including myself, have hypothesized that female characters are doing double duty in these plays, by representing a fictional female position in the tragic family and city and simultaneously serving as a location from which to explore a series of problematic issues that men prefer to approach indirectly and certainly not through their own persons. In this sense, the female acts investigated in this book are fe(male) acts designed not only by but for men.

Next page