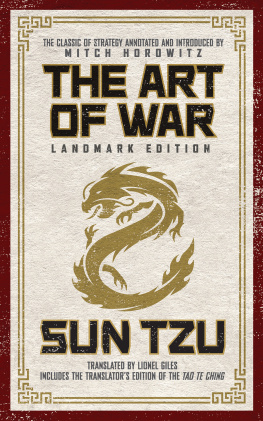

THE ART

OF WAR

Also available in the Condensed Classics Library

A MESSAGE TO GARCIA

ACRES OF DIAMONDS

ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS

AS A MAN THINKETH

HOW TO ATTRACT GOOD LUCK

HOW TO ATTRACT MONEY

PUBLIC SPEAKING TO WIN!

SELF-RELIANCE

THE ART OF WAR

THE GAME OF LIFE AND HOW TO PLAY IT

THE KYBALION

THE LAW OF SUCCESS

THE MAGIC LADDER TO SUCCESS

THE MAGIC OF BELIEVING

THE MASTER KEY TO RICHES

THE MASTER MIND

THE MILLION DOLLAR SECRET HIDDEN IN YOUR MIND

THE POWER OF CONCENTRATION

THE POWER OF YOUR SUBCONSCIOUS MIND

THE PRINCE

THE RICHEST MAN IN BABYLON

THE SCIENCE OF BEING GREAT

THE SCIENCE OF GETTING RICH

THE SECRET DOOR TO SUCCESS

THE SECRET OF THE AGES

THINK AND GROW RICH

YOUR FAITH IS YOUR FORTUNE

THE ART

OF WAR

by Sun Tzu

Historys Greatest Work on StrategyNow in a Special Condensation

Abridged and Introduced by

Mitch Horowitz

Published by Gildan Media LLC

aka G&D Media.

www.GandDmedia.com

The Art of War is estimated to have been written c. 500 BC

The English translation by Lionel Giles was published 1910

G&D Media Condensed Classics edition published 2019

Abridgement and Introduction copyright 2019 by Mitch Horowitz

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means, (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the author. No liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained within. Although every precaution has been taken, the author and publisher assume no liability for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

FIRST PRINT AND EBOOK EDITION: 2019

Cover design by David Rheinhardt of Pyrographx

Interior design by Meghan Day Healey of Story Horse, LLC.

ISBN: 978-1-7225-0190-7

eISBN: 978-1-7225-2289-6

CONTENTS

by Mitch Horowitz

INTRODUCTION

The Unlikeliest Classic

By Mitch Horowitz

S ince its first creditable English translation in 1910, the ancient Chinese martial text The Art of War has enthralled Western readers. First gaining the attention of military officers, sinologists, martial artists, and strategy aficionados, The Art of War is today read by business executives, athletes, artists, and seekers from across the self-help spectrum. This is a surprising destiny for a work on ancient warfare estimated to be written around 500 BC by Zhou dynasty general Sun Tzu, an honorific title meaning Master Sun. Very little is known about the author other than a historical consensus that such a figure actually existed as a commander in the dynastic emperors army.

What, then, accounts for the enduring popularity of a text that might have been conscripted to obscurity in the West?

Like the best writing from the Taoist tradition, The Art of War is exquisitely simple, practical, and clear. Its insights into life and its inevitable conflicts are so organic and soundTaoism is based on aligning with the natural order of thingsthat many people who have never been on a battlefield are immediately drawn into wanting to apply Sun Tzus maxims to daily life.

Indeed, this gentle condensation is intended to highlight those aphorisms and lessons that have the broadest general applicability. I have no doubt that as you experience this volume you will immediately discover ideas that you want to note and use. This is because Sun Tzus genius as a writer is to return us to natural principlesthings that we may have once understood intuitively but lost in superfluous and speculative analysis, another of lifes inevitabilities.

I have based this abridgment on the aforementioned and invaluable 1910 English translation by British sinologist Lionel Giles. Giles translation has stood up with remarkable relevance over the past century. Rather than laden his words with the flourish of late-Victorian prose, Giles honored the starkness and sparseness of the original work. I have occasionally altered an obscure or antiquated term, but, overall, the economy and elegance of Giles translation is an art form in itself, and deserves to be honored as such.

Why then a condensation at all? In some instances, Sun Tzu, a working military commander, necessarily touched upon battlefield intricaciessuch as the fine points of terrain or attacking the enemy with firethat prove less immediately applicable to modern life than his observations on the movements and motives of men. In a few spots I also add a clarifying note to bring out Sun Tzus broader points.

I ask the reader to take special note of Sun Tzus frequent references to adhering to the natural landscape. It is a classically Taoist approach to blend with the curvature and qualities of ones surroundingsto find your place in the organic order of things. Within the Vedic tradition this is sometimes called dharma. Transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson also notes the need to cycle yourself with the patterns of nature. As the great Hermetic dictum put it: As above, so below.

Another key to Sun Tzus popularity is the manner in which he unlocks the universality of true principles. What applies in warfare, if authentic, must apply to other areas of life. Human nature is consistent. So are the ebb and flow of events, on both macro and intimate levels. Be on the watch for this principle throughout the text.

Another central aspect of Sun Tzus thoughtagain in harmony with Taoismis that the greatest warrior prevails without ever fighting. If a fighter has observed conditions, deciphered the enemy, and diligently prepared and marshaled his forces, the ideal is to overwhelm his foe without shooting a single arrow. Supreme excellence, Sun Tzu writes, consists in breaking the enemys resistance without fighting.

If an attack does prove necessary, it should be launched with irresistible force, like a seismic shifting of the earth. After your enemys defeat, quickly return to normalcy. In war then, the master writes, let your object be victory, not lengthy campaigns. Sun Tzu warns against protracted operations. There is no instance of a country having benefited from prolonged warfare, he writes.

Rather than seek glory, Sun Tzu counsels that the excellent commander practices subtlety, inscrutability, watchfulness, and flexibility. The good fighter, he writes, should be like water: dwelling unnoticed at his enemys lowest depths and then striking with overwhelming power at his weakest points, the way a torrent of water rushes downhill. This constitutes ideal preparation and formation for attack: practice patience, carefully study the enemy, know his limits and strengths and your own, never be lured or tricked into battleand then strike with ferocity. And never fight unless victory is assured.

If I had to put The Art of War into a nutshell, I would use this one of the masters maxims: Let your plans be dark and impenetrable as night, and when you move, fall like a thunderbolt.

In a sense, The Art of War

Next page