The Art of War

COMPLETE TEXTS AND COMMENTARIES

The Art of War

Mastering the Art of War

The Lost Art of War

The Silver Sparrow Art of War

Sun Tzu

Translated by Thomas Cleary

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2011

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1988, 1989, 1996, 2000 by Thomas Cleary

The Lost Art of War is reprinted by special arrangement with HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

See for a continuation of the copyright page

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: Chinese, Armored guardian (tomb figure), Tang dynasty, 700750, buff earthenware with polychromy and gilding, ht.: 96.5 cm, Gift of Russell Tyson, 1943.1139, photo by Robert Hashimoto, photo The Art Institute of Chicago.

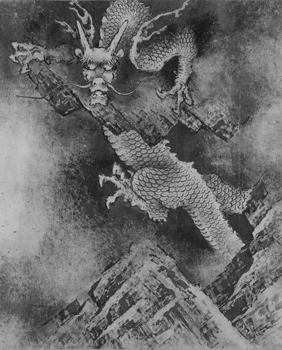

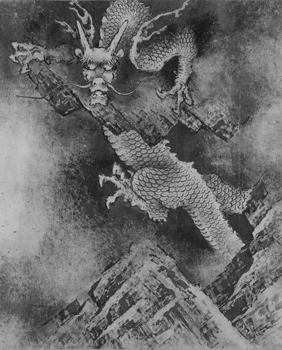

Frontispiece: Nine Dragons (detail), Chen Rong, Chinese, Southern Song dynasty, dated 1244, 2003 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Francis Gardner Curtis Fund; 17.1697.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Classics of strategy and counsel. Selections.

The art of war: complete texts and commentaries/translated by Thomas Cleary.1st. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2730-1

ISBN 978-1-59030-054-1

1. Military art and science. 2. Strategy. 3. Management. I. Cleary, Thomas F., 1949 II. Title.

U104.C48423 2003

355.02dc21

CONTENTS

SUN TZU

The Art of War (Sunzi bingfa/Sun-tzu ping-fa), compiled well over two thousand years ago by a mysterious Chinese warrior-philosopher, is still perhaps the most prestigious and influential book of strategy in the world today, as eagerly studied in Asia by modern politicians and executives as it has been by military leaders and strategists for the last two millennia and more.

In Japan, which was transformed directly from a feudal culture into a corporate culture virtually overnight, contemporary students of The Art of War have applied the strategy of this ancient classic to modern politics and business with similar alacrity. Indeed, some see in the successes of postwar Japan an illustration of Sun Tzus dictum of the classic, To win without fighting is best.

As a study of the anatomy of organizations in conflict, The Art of War applies to competition and conflict in general, on every level from the interpersonal to the international. Its aim is invincibility, victory without battle, and unassailable strength through understanding of the physics, politics, and psychology of conflict.

This translation of The Art of War presents the classic from the point of view of its background in the great spiritual tradition of Taoism, the origin not only of psychology but also of science and technology in East Asia, and the source of the insights into human nature that underlie this most revered of handbooks for success.

In my opinion, the importance of understanding the Taoist element of The Art of War can hardly be exaggerated. Not only is this classic of strategy permeated with the ideas of great Taoist works such as the I Ching (The Book of Changes) and the Tao-te Ching (The Way and Its Power), but it reveals the fundamentals of Taoism as the ultimate source of all the traditional Chinese martial arts. Furthermore, while The Art of War is unmatched in its presentation of principle, the keys to the deepest levels of practice of its strategy depend on the psychological development in which Taoism specializes.

The enhanced personal power traditionally associated with application of Taoist mental technology is in itself a part of the collective power associated with application of the understanding of mass psychology taught in The Art of War. What is perhaps most characteristically Taoist about The Art of War in such a way as to recommend itself to the modern day is the manner in which power is continually tempered by a profound undercurrent of humanism.

Throughout Chinese history, Taoism has been a moderating force in the fluctuating currents of human thought and action. Teaching that life is a complex of interacting forces, Taoism has fostered both material and mental progress, both technological development and awareness of the potential dangers of that very development, always striving to encourage balance between the material and spiritual sides of humankind. Similarly, in politics Taoism has stood on the side of both rulers and ruled, has set kingdoms up and has torn kingdoms down, according to the needs of the time. As a classic of Taoist thought, The Art of War is thus a book not only of war but also of peace, above all a tool for understanding the very roots of conflict and resolution.

Taoism and The Art of War

According to an old story, a lord of ancient China once asked his physician, a member of a family of healers, which of them was the most skilled in the art.

The physician, whose reputation was such that his name became synonymous with medical science in China, replied, My eldest brother sees the spirit of sickness and removes it before it takes shape, so his name does not get out of the house.

My elder brother cures sickness when it is still extremely minute, so his name does not get out of the neighborhood.

As for me, I puncture veins, prescribe potions, and massage skin, so from time to time my name gets out and is heard among the lords.

Among the tales of ancient China, none captures more beautifully than this the essence of The Art of War, the premiere classic of the science of strategy in conflict. A Ming dynasty critic writes of this little tale of the physician: What is essential for leaders, generals, and ministers in running countries and governing armies is no more than this.

The healing arts and the martial arts may be a world apart in ordinary usage, but they are parallel in several senses: in recognizing, as the story says, that the less needed the better; in the sense that both involve strategy in dealing with disharmony; and in the sense that in both knowledge of the problem is key to the solution.

As in the story of the ancient healers, in Sun Tzus philosophy the peak efficiency of knowledge and strategy is to make conflict altogether unnecessary: To overcome others armies without fighting is the best of skills. And like the story of the healers, Sun Tzu explains there are all grades of martial arts: The superior militarist foils enemies plots; next best is to ruin their alliances; next after that is to attack their armed forces; worst is to besiege their cities.

Just as the eldest brother in the story was unknown because of his acumen and the middle brother was hardly known because of his alacrity, Sun Tzu also affirms that in ancient times those known as skilled warriors won when victory was still easy, so the victories of skilled warriors were not known for cunning or rewarded for bravery.

This ideal strategy whereby one could win without fighting, accomplish the most by doing the least, bears the characteristic stamp of Taoism, the ancient tradition of knowledge that fostered both the healing arts and the martial arts in China. The

Next page