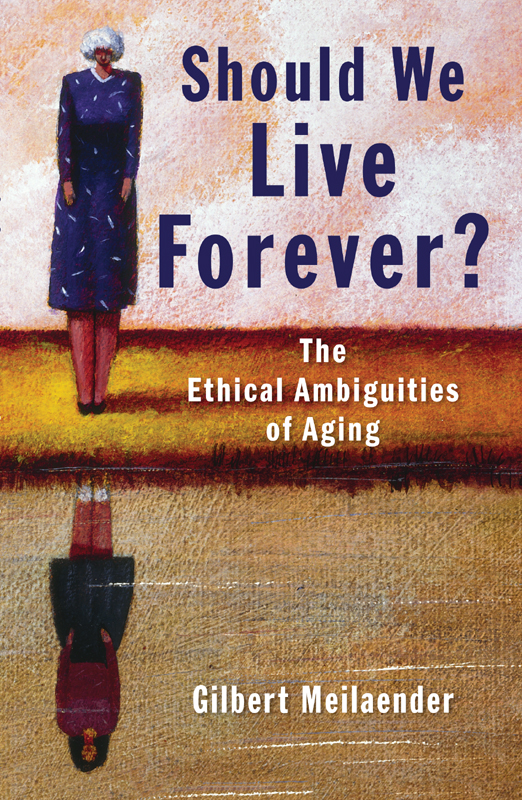

Should We Live Forever?

Should We Live Forever?

The Ethical Ambiguities of Aging

GILBERT MEILAENDER

William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K.

2013 Gilbert Meilaender

All rights reserved

Published 2013 by

WM. B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING CO.

2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 /

P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K.

www.eerdmans.com

17 16 15 14 13 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meilaender, Gilbert, 1946

Should we live forever : the ethical ambiguities of aging /

Gilbert Meilaender.

p. cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8028-6869-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4674-3754-7 (epub)

1. Aging Religious aspects Christianity. 2. Aging Moral and ethical aspects. 3. Death Moral and ethical aspects. 4. Older Christians Religious life. 5. Gerontology Moral and ethical aspects.

I. Title.

BV4580.M45 2013

248.85 dc23

What the Bird Said Early in the Year from Poems by C. S. Lewis. Copyright 1964 by the Executors of the Estate of C. S. Lewis and renewed 1992 by C. S. Lewis Pte. Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of the C. S. Lewis Company Ltd.

An Ancient Story by John Hall Wheelock, first published in the Sewanee Review, vol. 81, no. 1, Winter 1973. Copyright 1973 by the University of the South. Reprinted with the permission of the editor.

Excerpts from Night Thoughts in Age and Song on Reaching Seventy by John Hall Wheelock. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from This Blessed Earth by John Hall Wheelock. Copyright 1973, 1974, 1975, 1976 by John Hall Wheelock. Copyright 1978 by the estate of John Hall Wheelock. All rights reserved.

To Nathanael and Flora

whose youth is both burden and blessing

Contents

Science continues to be a channel for magic the belief that for the human will, empowered by knowledge, nothing is impossible.

John Gray, The Immortalization Commission

Do not cast me off in the time of old age;

forsake me not when my strength is spent....

till I proclaim thy might

to all the generations to come.

Psalm 71:9, 18b

A FEW YEARS ago I was fortunate enough to receive a grant from the University of Chicagos New Science of Virtues Project, funded by the John Templeton Foundation. The focus of my project was to be virtue (and virtues) in relation to anti-aging research; and, at least initially, I believe I was thinking in terms of a rather standard bioethical exploration of ongoing research into age-retardation and extension of the life span. It was not long, though, before it became apparent to me that the project could not be done in a metaphysically neutral way. Inevitably, religious beliefs kept creeping in. I have not so much tried to defend those beliefs as to explore their significance for human aging and attempts to retard it. That we often desire, even greedily desire, longer life is clear; whether what we desire is truly desirable is harder to say.

The classical understanding of virtue referred to what philosophers in recent decades have come to call human flourishing the excellence that realizes and expresses the full potential of our human nature. Because that nature is an embodied one, we might suppose that, whatever human flourishing involves, it must include the aging and decline that characterize bodily organisms. Since, however, we are rational animals, our full potential may be realized only through our freedom to remake ourselves, transcending indefinitely the limits of the body. We try rightly, I think to cure and even eradicate disease, but whether we should approach aging in the same way is deeply puzzling. Still more, when we notice that some of the more ambitious proposals for age-retardation seem rather like a desire to escape bodily existence itself, we may begin to wonder whether the aim is to transcend or to transgress the bodys limits.

Moreover, if we are not only rational but also ecstatic animals (whose self is, as Sren Kierkegaard put it, a relation of temporal and eternal), there can be no human flourishing that is isolated from our relation to God. Prolongation of this life, however long, could not really satisfy the thirst that we experience. Still, no one should suppose that religious belief eliminates whatever is puzzling about the project of life-extension. In fact, it may in some ways complicate our struggle to gain clarity. Thus, George Weigel recounts Cardinal Francis George having asked a few years ago, with a vivid sense of the questions paradoxical strangeness: Do you realize that were going to spend the rest of our lives trying to convince people that suffering and death are good for you? If this life is Gods good gift, more of it seems like a good thing; yet the thirst for more may easily become not the way that leads to God but an end in itself.

The first three chapters that follow attempt to think, from several different angles, about whether more life, indefinitely more life, is a goal we ought to pursue. In the first chapter I survey some of what we know about aging and age-retardation, in order to suggest that science cannot itself tell us what our aims should be. And I note though not, I hope, without recognizing the worth of more life what would be lost if a substantial increase in the maximum human life span turned old age into a kind of endless middle age and drastically altered the relation between the generations.

In the second chapter I consider some of the most far-reaching, perhaps in some cases bizarre, proposals to extend life by detaching it from its organic base. Whether this is simply transcending the givens of our current existence or transgressing the limits that should characterize our humanity is, of course, a fundamental question. Confidence in historical progress is not the same as Christian hope. Only to the degree that we find ways to honor the body and to understand ourselves as on the way to a flourishing not of our own making can the virtue of hope really shape our being and doing.

In the third chapter I suggest that no approach to the question of life-extension and age-retardation will be free of normative commitments. Indeed, the palpable thirst for an indefinitely extended life, for an escape from mystery and contingency, animates the project of life-prolongation more than moderns might wish to admit. Observing that science and the occult have interacted at many points, the philosopher John Gray writes that, in the struggle for a kind of humanly produced immortality, the hope of life after death has been replaced by the faith that death can be defeated. Yet, in our world that thirsts for longer life there is, nonetheless, a substantial body of literature arguing that immortality, whether of our own making or of Gods, would be undesirable. To examine it is to see that there is no single or neutral understanding of immortality.

It is also important to reflect upon the project of indefinite life-extension from the perspective not simply of virtue (in the singular) but of particular virtues. The virtues are not just means to an end; they are elements of a life well lived. In the fourth, fifth, and sixth chapters I examine three aspects of a virtuous life in relation to the project of indefinite life-extension. There are no perfect terms to mark out these elements of a life well lived. But in pondering the relation between the generations and the ways And in order to think about lifes stages, I ask whether a