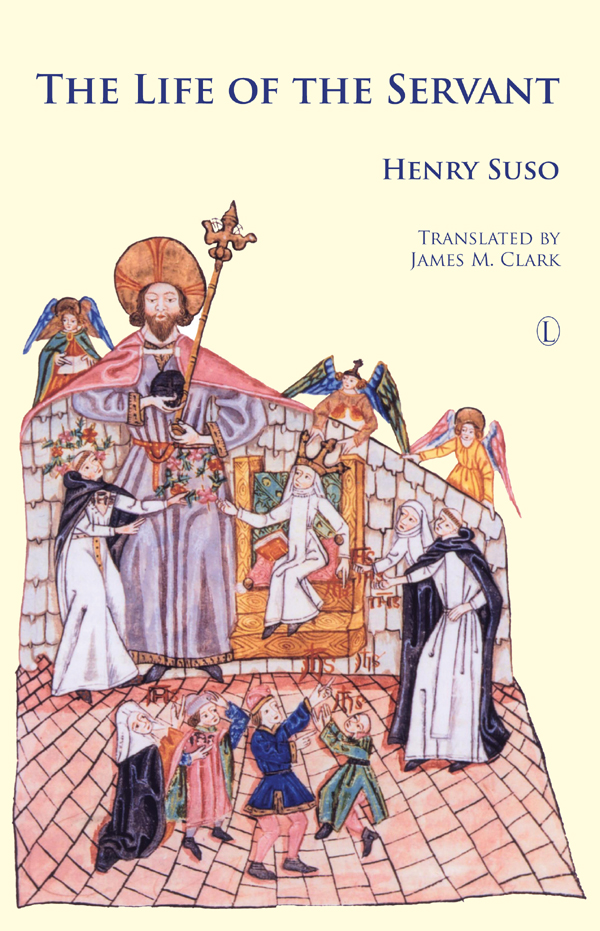

The Life of the Servant

The Life of the Servant

Henry Suso

Translated by James M. Clark

The Lutterworth Press

The Lutterworth Press

P.O. Box 60

Cambridge

CB1 2NT

United Kingdom

www.lutterworth.com

publishing@lutterworth.com

ISBN: 978 0 7188 4243 7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A record is available from the British Library

First published by James Clarke & Co, 1952

Paperback Edition, 1982

Reprinted by The Lutterworth Press, 2014

Copyright James Clarke & Co, 1952

All rights reserved. No part of this edition may be reproduced, stored electronically or in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the Publisher (permissions@lutterworth.com).

CONTENTS

SUSOs autobiography is a classic of religious literature, worthy to be placed beside such works as the Confessions of St. Augustine or The Imitation of Christ. It holds a unique position in the rich and varied productions of the German mystics, since it is the only one in which we hear at first hand the authentic experiences of the author. This cannot be said of the writings of that arch-plagiarist Rulman Merswin, which have, moreover, been very much overrated. Eckhart and Tauler scarcely ever refer to their own experiences. They almost invariably speak with self-effacing objectivity. Suso alone tells us in some detail of his own visions, ecstasies and revelations. His Life was never intended for publication, and owes its preservation to an accident. What he confided to his spiritual daughter was meant for her ears alone. In order to console a highly gifted woman in the acute physical sufferings that preceded her death, he told her details of his own life that would otherwise have remained for ever unsaid.

The great value of these utterances lies first in their remarkable sincerity; secondly, in their unsurpassed poetic beauty. They reveal to us a pure and saintly life, lived in the service of a spiritual ideal. Suso was a saint, in the fullest and best sense of the word. He strove with all the energy of an ardent nature to share the life of Christ, both on the physical and on the spiritual plane, to imitate His sufferings, no less than to show forth His divine love and compassion.

Rarely does it happen that such intense spirituality is found combined with such extraordinary literary powers. Saints are rare enough, but a saint who is also a poet of no mean order is rare indeed. Suso was reared in the home of the Minnesang, in the idyllic countryside of his beloved Swabia. He inherited the love of chivalry; he was the scion of a noble house. From his childhood he had heard the songs inspired by that amour courtois that had come to Germany from Provence. But instead of singing the praise of an earthly lady, he celebrated a heavenly love, which far surpassed all mundane affection.

He was in many respects a true son of his age. In his veneration of the Virgin and the saints, his theological convictions, his almost incredible austerities, as in so many other ways, his outlook was that of the cloister. But we find also in his writings an element of the universal. Every succeeding generation has found in him a perennial source of inspiration. Protestants and Catholics alike are to be found among his admirers and disciples.

We live in an extremely materialistic age, an age in which the things of the mind and the spirit mean little or nothing to large sections of the community. In common with the best of his contemporaries, Suso saw the world of material things as something transient and deceptive, as compared with the spiritual and invisible world, which was for him the one supreme reality. Here lies the relevance of his works for us to-day. He is the best antidote for soul-destroying materialism.

Suso tells his story, now in homely simple speech, now in the imaginative language of poetry, and without any strict regard for chronology. He briefly characterizes his father as a very worldly man, and his mother as a gentle, pious soul. It was in order to commemorate his mothers name that young Heinrich von Berg assumed her family name of Suso or Sss. Being unable to take part in knightly pursuits because of his frail health, he was sent to the Dominican friary of Constance. His admission

He tells us that his companions in the friary were frivolous and uncongenial: they treated him as a crazy eccentric. There are brief references to his studies at Cologne and the beneficent influence of his wise and saintly master, Eckhart. Suso describes in some detail his severe mortifications of the flesh, and adds that, following a divine command, he finally threw his instruments of torture into the river.

After his first phase as a recluse, which had its vicissitudes of celestial consolation and visitations of doubt or despair, comes the pastoral phase of his life, in which he visited other friaries and convents, ministering to the inmates, preaching, teaching, and giving spiritual guidance to his penitents. In this second period, he suffered physical ills, and later persecution and calumny. He persevered in his efforts, and we know from other sources that he finally reached peace and serenity. In the midst of his troubles he was elected by his brethren Prior of Constance, and acquitted himself well in his onerous office, relying more on prayer than on worldly wisdom.

There are some delightful little stories interwoven in the narrative. Suso is seen to advantage in the tale of his sister, the renegade nun (Chapter XXIV), that of the robber (XXVI), of the wicked woman who slandered him (XXXVIII), the conversion of the frivolous girl (XLII). There may be here and there some slight embellishment of the facts, for literary effect. After all, Suso was not writing a history, but an edifying work, and he would have seen no harm in using a poets licence.

The supernatural plays a large part in the story, and some critics have taken objection to this. It may be pointed out that Suso had unquestioning faith in a spiritual order of the world. The miraculous was for him an unchallengeable fact. In every event he saw the hand of God. But that he was not over-credulous, but was quite able to distinguish between fact and fiction, is shown by the story of the bleeding crucifix, concerning which he refused to express an opinion. We may also note how carefully he says: It seemed to him in a vision.

In order to reduce this work to reasonable proportions, some abridgment was necessary. As it happens, the third part of the Life consists of Maxims, which have no logical connection with the autobiography proper. Moreover, in the other two parts there are occasional moralizing or reflective passages and some repetitions. But no essential trait of Suso has been omitted, and the narrative gains by these excisions in unity and compactness.

With characteristic modesty, Suso never mentions his name in the book. Most of the manuscripts have no title, apart from a rubric that runs, This book is called Suso, which means This is Susos book: an evident addition by a later scribe. But in one early manuscript we find the title The Life of the Servant, which I have here used. It is not inappropriate, because Suso refers to himself as The Servant of Eternal Wisdom, or simply The Servant.

JAMES M. CLARK.

GLASGOW.

See below, pp. 6465.