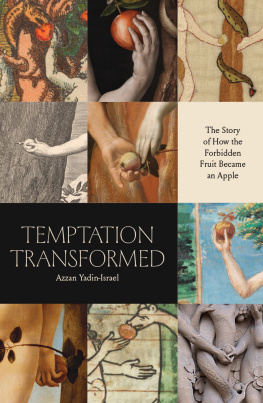

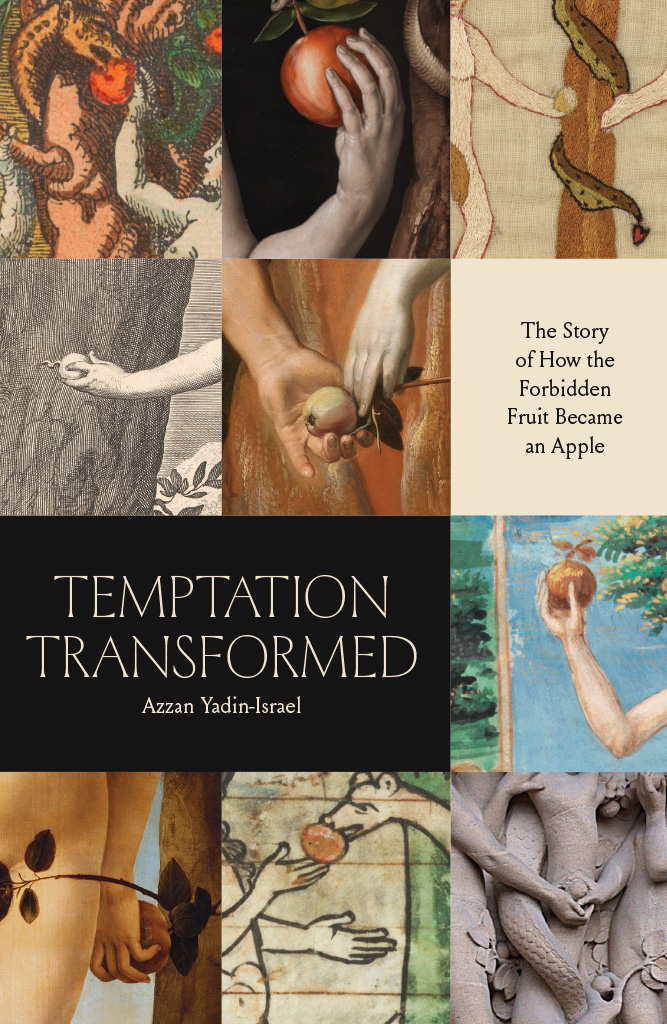

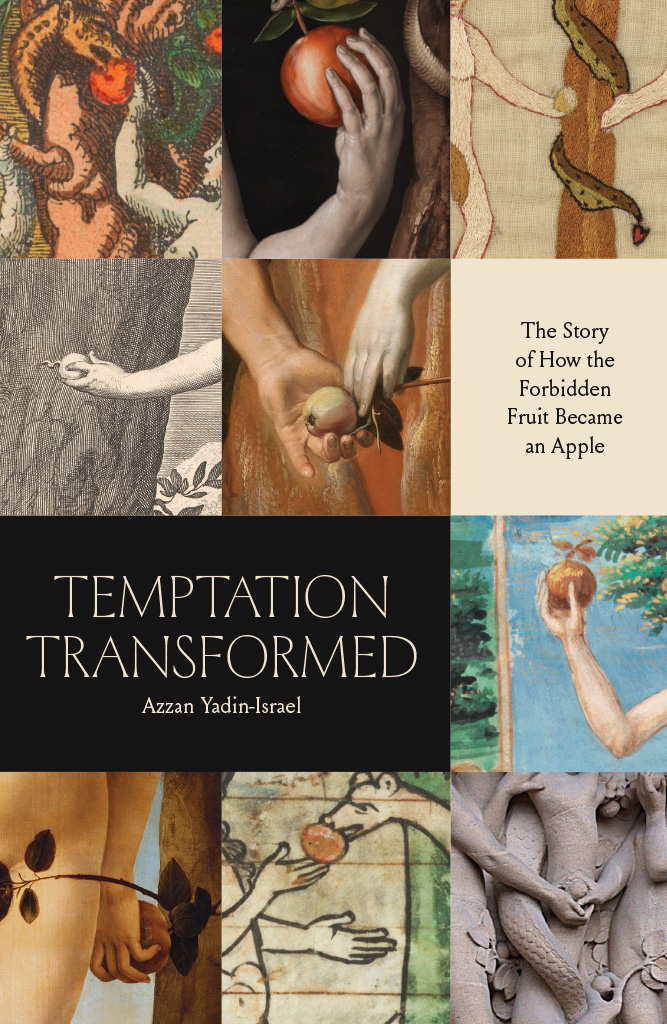

Temptation Transformed

Temptation Transformed

The Story of How the Forbidden Fruit Became an Apple

AZZAN YADIN-ISRAEL

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2022 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-82076-7 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-82212-9 (e-book)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226822129.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Yadin-Israel, Azzan, author.

Title: Temptation transformed: the story of how the forbidden fruit became an apple / Azzan Yadin-Israel.

Description: Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022004670 | ISBN 9780226820767 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226822129 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Bible. GenesisCriticism, interpretation, etc. | ApplesReligious aspects. | Temptation in the Bible. | Eden. | Apples in art. | Temptation in art.

Classification: LCC BS 1237. Y 33 2022 | DDC 222/.1106dc23/eng/20220209

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022004670

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To my teachers:

At Berkeley, the Hebrew University, and Cleveland Heights High School

That the Forbidden fruit of Paradise was an Apple, is commonly beleeved.

THOMAS BROWNE , Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1658)

Contents

Plates

Figures

Maps

The Curious Case of the Apple

The Bible contains many mysteries, but the identity of the forbidden fruit, it seems, is not one of them. It is, by common consent, an apple, an identification that has freighted the apple with symbolic meaning like no other fruit. From Roz Chasts New Yorker cartoon of the serpent temptingly informing Eve that its a Honeycrisp! to the feminine hands cradling a cardinal red apple on the cover of Stephenie Meyers Twilight, the apple is everywhere the symbol of forbidden knowledge and temptation.

Of course, common consent is not proof that the Book of Genesis intended an apple. In fact, there are compelling reasons to assume otherwise. The apple does not appear in the Fall of Man narrative, nor anywhere else in the Hebrew Bible, undoubtedly because the grafting technique essential to apple cultivation was not known in ancient Israel. Furthermore, the ascent of the apple is relatively recent; for centuries, the preferred forbidden fruits were the fig and the grape, along with other less prominent species. How, then, did the apple become the most popular forbidden fruit?

This book aims to answer that question. surveys the ancient Jewish and Christian sources depicting the forbidden fruit: the Hebrew Bible and its ancient translations (the Greek Septuagint, Latin Vulgate, and Aramaic Targums); biblical pseudepigrapha such as the Book of Enoch; and rabbinic and early Christian biblical commentaries. Two important conclusions emerge: these works do not mention the apple, and they do identify other fruit species as the forbidden fruitprimarily the grape and the fig. The enduring popularity of these fruits is significant because one of the striking aspects of the apples ascent is the way it reshaped the entire forbidden-fruit landscape, eradicating species that had peacefully coexisted for centuries.

questions the reigning theory that links the apples rise to an accident of the Latin language, namely, that it designates both evil and apple with the word malum. The logic seems compelling: the forbidden fruit caused the Fall of Man, introducing death into the worlda terrible malum (evil) if ever there was one. What fruit, then, would medieval scholars who read and interpreted the Bible in Latin consider better suited to the role than the malum (apple)? This hypothesis (the malum hypothesis) centers on the Fall of Man narrative in Genesis 3, but claims additional support from Song of Songs 8:5, a verse whose Latin translation can be interpreted as referring to Eves corruption under an apple tree.

However, there is scant evidence for the malum hypothesis. Medieval commentaries on Genesis and Song of Songs 8:5 almost never refer to the two meanings of malum, and many scholars contend (or imply) that the forbidden fruit was a fig, including Saint Augustine, Alcuin of York, and Thomas Aquinas. Moreover, the Christian allegorical reading of the Song of Songs regularly associated the apple with Christnot the cause of original sin, but its salvation. Most significantly, the Latin authors are unaware of any tradition identifying the forbidden fruit with the apple. Thus, a mystery: not only do the Latin sources not support the malum hypothesis, they force us to grapple with the questions of where and when the apple tradition first appeared.

To answer these questions, explores the rich iconographic tradition of the Fall of Man. Drawing on nearly five hundred Fall of Man scenes, the chapter demonstrates that the apple is virtually absent before the twelfth century. Then, the apple begins to appear in French Fall of Man scenes and quickly becomes the dominant forbidden fruit, rapidly supplanting figs, grapes, and all other species. Something similar occurs in England, Germany, and the Low Countries, though the apple appears slightly later and its spread is more gradual. Italy, however, remains loyal to the fig for centuries, with leading Italian artists depicting the forbidden fruit as a fig well into the sixteenth century. These findings prompt three questions: Why did the apple appear in twelfth-century France? Why was its spread so irregulara quick ascent in England and Germany, but not in fig-friendly Italy? And why, in the regions that embraced the apple, was there such a disparity between the forbidden fruits of the artists and those of the Latin commentators?

answers these questions. Here, I argue that while scholars have sought to explain the apples rise in theological terms, it was actually an unintended consequence of two distinct historical developments: a series of semantic shifts and the proliferation of Fall of Man narratives in the European vernaculars. Words that meant fruit in early French, English, and German later came to denote the apple, and, consequently, sources that used these words to designate the forbidden fruit were interpreted as referring to a forbidden apple.

I have tried throughout to make my argument as accessible as possible. Foreign-language quotations appear in English translation, with the original passage reproduced in the endnotes when necessary for my analysis. All dates are CE (ne AD), unless otherwise noted.

Like any broad and vigorously interdisciplinary study, this book entails some risk. I do not claim to have a full command of the Latin commentary tradition, medieval Christian iconography, or European vernacular languages and their literatureseven though each of these fields plays a critical role in my argument. I undoubtedly commit errors both of omission and of commission. Yet I believe such risks are justified when they allow us to solve historical riddles that would otherwise elude us.

Next page