Foreword

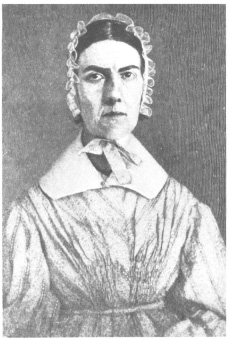

A more unlikely social background could hardly be imagined than the one from which Angelina Grimk came to become a leading woman figure in nineteenth-century movements for the emancipation of slaves and of her own sex. She was born February 20, 1805, to a family of wealth and high station. Her South Carolina home was in the City of Charleston, a place where family name was expecially revered, and she never ceased to hold the name of Grimk high. John Faucheraud Grimk, her father, was Oxford educated, a distinguished lawyer, and a state supreme court judge. Several of her brothers became well-known professional men, learned in the law and highly regarded. Formal higher education was not available to a woman, though Angelina was self-educated to a high degree. She came of a people who were owners of many slaves. Her family lived in the city but drew their wealth from a plantation two hundred miles distant. Angelina saw little of the Grimk slaves, except for those who served the household on Charlestons East Bay. It is true that she saw slaves by the hundreds on Charlestons streets and those who served in the stately homes of relatives and friends. Thus what Angelina knew was luxury and ease, as these were made possible by ample means and numerous slaves, although as matters turned out she was far from protected from sights, sounds, and experiences that would come to haunt her life.

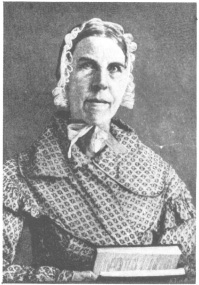

There were many children in the Grimk family, fourteen in all, with the three who died in childhood. Angelina was the fourteenth child. Of the eleven living children, only two among them turned actively against slaveryAngelina and a middle child named Sarah, who was twelve years older. Sarah, from the first, was Angelinas mentor and became a strange and dubious kind of catalytic agent at times of major crisis for Angelina. At no time was this clearer than when Angelina was confronted with the clear-cut issue: could she continue to condone human slavery? Not that Sarah put the matter directly; it was put by certain Friends whom Sarah knew in her Philadelphia Friends Meeting. Angelina met the slavery issue head-on, with consequences that Sarah never dreamed could ensue.

The years that preceded Angelinas career, beginning around the time she came of age, are rich in materials from Angelinas and Sarahs letters and diaries. There are also letters from their mother, Mary Smith Grimk and, at certain times, from others. Thus the record is full, explicit, revealing, and so extensive that only significant portions can be given. Of course all of the documents contribute to the authors knowledge of Angelinas development, motives, and character.

Since her early twenties Angelina Grimk had felt the pressures of her great potential gifts and the urgings of her ambitious nature, and these she expressed in perhaps the only terms open to a woman of her time and place. She experienced conversion, a religious upheaval that demanded a full and complete commitment. While in that day it was not at all unusual for a femalegirl or womanto experience conversion and become more religious in her devotion to her church, the conversion customarily brought no change in her traditional female functions. On the contrary, Angelinas experience was unusual. In the language of her day, she, a woman, felt called to some great mission, but at the time she did not know where the call would lead her. The conviction that she was meant to do important work never left Angelina in the ensuing years, though she rarely expressed what she sensed it was that drove her onthe need to use her powers and to have them be of useand when she spoke of freedom this was part of what she meant.

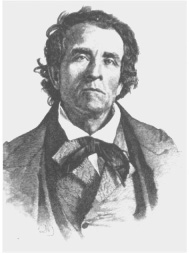

It was more than mere chance that the antislavery movement became for Angelina the means and symbol of her mission. When she settled in Philadelphia in late 1829, antislavery groups throughout the North and Middle West were moving ever closer to a merger The founding convention met in late 1833 in Philadelphia, and from this time on, all through the 1830s, the American Anti-Slavery Society was a vigorous, vociferous, controversial force that was confronted by an ever-rising hostile opposition. The more it was attacked, the more unyielding grew its principlesabolition of slavery, immediate emancipation. Many of the leaders were of outstanding qualities, men of various vocations, all of deep commitment, who, while they came to differ, remained devoted to abolition, and, in these first years, their differences were muted. With very few exceptions, they were religious people, so the abolition movement was religiously motivated. The leaders practiced prayer, they used churches for their meetings, and they called on fellow Christians to be consistent in their beliefs and to condemn human slavery as a sin in Gods eyes. The number of abolitionist publications showed a rapid increase: Garrisons paper, the Liberator, was founded in the early thirties; the Emancipator was the official organ of the Anti-Slavery Society; tracts poured from the presses as the decade went on, with a wide distribution in local societies; abolitionist speakers began to move from place to place, meeting ever-growing interest and often violent hostility. Within the movement, the 1830s were a creative time-stimulating, exciting, and full of hope for the converted, who felt the thrill of belonging to this company of men and women so committed to a noble human cause.

By 1834 Angelina was awakened, and in the antislavery movement she recognized her call. In fact, as she began, she was merely a member of a small, local female antislavery society. The fact that her name became notorious within a matter of months is one of the more remarkable features of her career. Thenceforth she was swept into uncharted seas, in which, despite her womanhood and the time and place, she found the power somehow to steer a clear direction.

One strong force in the abolition movement came to Angelinas aid at this crucial time, and it is not too much to surmise that it was an essential element. This was the company of female abolitionists. The American Anti-Slavery Society was composed of men and women, although the women, it must be said, were in an auxiliary position. At least they were in the mens eyes, a fact that came to light in highly vocal terms once the question of womans status became acute within the movementan issue, be it said, that Angelina and Sarah Grimk, more than any others, helped to precipitate. In the mid-1830s many womens groups existed, usually called Female Anti-Slavery Societies. They were active and vocal, but they were separate from the mens organizations. At the founding convention in 1833, there were only men delegates; women had no vote. A few well-known women were allowed in the hall. Lucretia Mott, a noted Hicksite Quaker minister and an outstanding abolitionist in Philadelphia and beyond, was permitted the floor to say a few words. Among the most active of the womens abolitionist groups were those in Philadelphia, New York, and Massachusetts, though there were many local societies throughout the East and Middle West. These women gave of their energies in wide-ranging activities: they circulated petitions urging Congress to act; they sold antislavery tracts and subscriptions to their papers; they arranged public meetings to hear antislavery speakers; when a slave escaped and his case came before a northern court, they aroused public indignation for fear the fugitive would be returned to his slavery. Even at their own gatherings, hostile mobs sometimes would gather. These women expected danger and were known for their courage.